Personal protective equipment (PPE) is designed to maximize protection when working in a hazardous environment. PPE to protect against infections may range from a common mask, gown, and goggles to the more extensive HazMat Level A, which includes a positive pressure, full face mask self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) or a positive pressure, supplied air respirator with escape SCBA; a totally encapsulated chemical- and vapor-protective suit; inner and outer chemical-resistant gloves; and a disposable protective suit, gloves, and boots. HazMat Level A is needed in ultra-high-risk situations like exposure to Ebola.

Minimum standards for PPE are set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Physicians can supply their own PPE if it meets or exceeds the OSHA standard. Employers are, however, primarily responsible for PPE use and should select and provide PPE to health care workers. Workers must be trained on and demonstrate that they understand the following:

- When to use PPE;

- What PPE is necessary;

- How to properly don, use, and doff PPE in a manner that prevents self-contamination;

- How to properly dispose of or disinfect and maintain PPE; and

- The limitations of PPE.

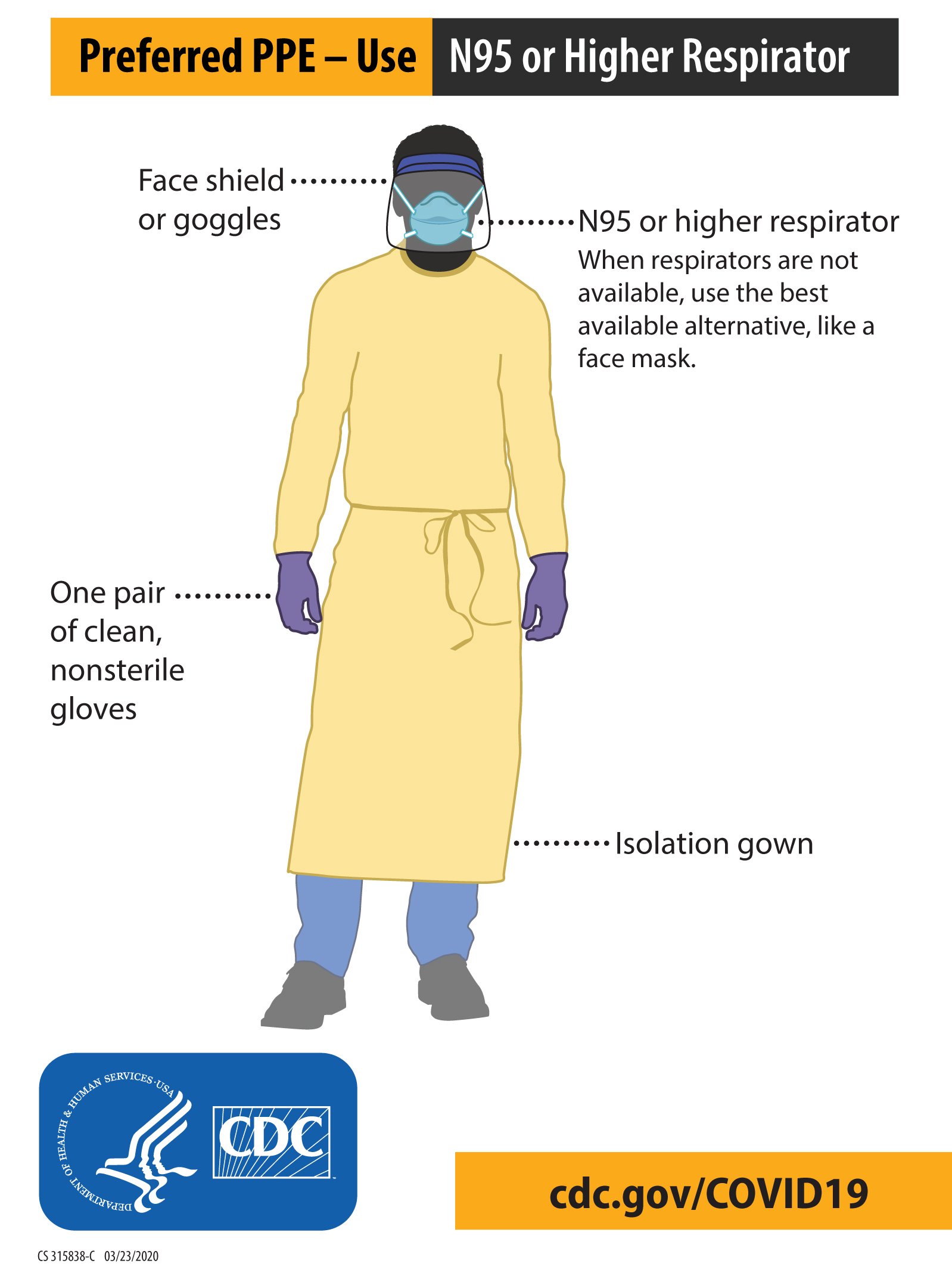

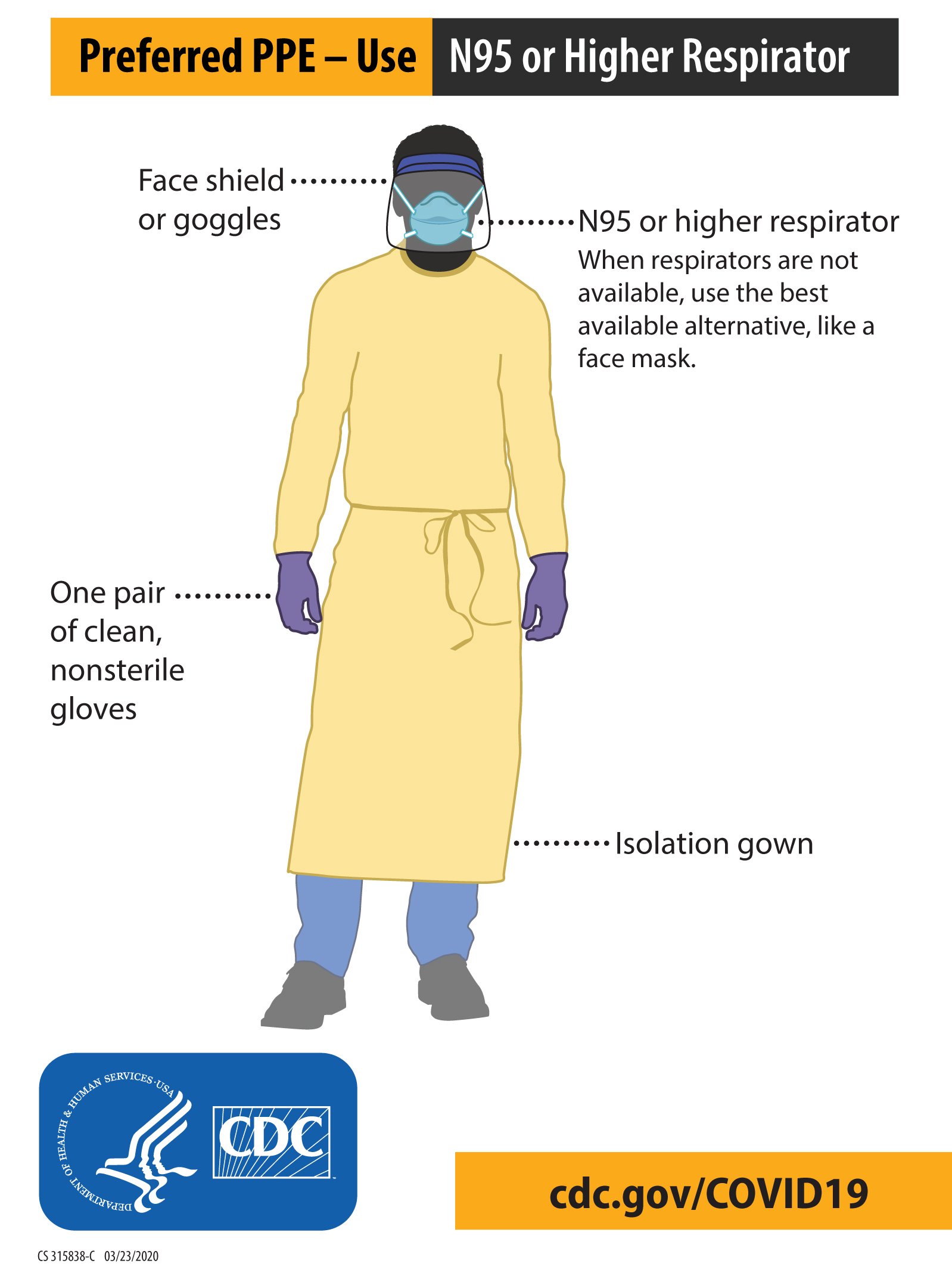

Any reusable PPE must be properly cleaned, decontaminated, and maintained after and between uses. Facilities should have policies and procedures that describe a recommended sequence for safely donning and doffing PPE. The PPE recommended when caring for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 includes (Figure 3.1):

- Masks

- Put on an N95 mask before entering the patient’s room or care area. Cloth face coverings are not PPE and should not be worn when caring for COVID-19 patients or in any other situation where an N95 mask is warranted.

- N95 respirators or respirators that offer a higher level of protection should be used when performing or when present during an aerosol-generating procedure. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting and closing the door to the patient’s room or care area. Hand hygiene should be performed after discarding the respirator.

- If reusable respirators (eg, powered air-purifying respirators [PAPRs]) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to the manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to reuse.

- Respirators with exhalation valves should not be used in situations where a sterile field must be maintained because the exhalation valve allows unfiltered exhaled air to escape into the sterile environment.

- Eye protection

- Put on eye protection (ie, goggles or a disposable face shield that covers the front and sides of the face) before entering the patient’s room or care area. Personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are not adequate eye protection.

- Health care workers who wear glasses will experience fogging of their glasses when wearing a face mask. This can be prevented by using the simple method known as the surfactant effect. Immediately before wearing a face mask, wash the glasses with soapy water and shake off any excess water. Then, let the glasses air dry or gently dry them off with a soft tissue before putting them back on to prevent them from fogging up when the face mask is worn.

- Remove eye protection before leaving the patient’s room or care area.

- Reusable eye protection (eg, goggles) must be cleaned and disinfected according to the manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to reuse. Disposable eye protection should be discarded after use.

- Gloves

- Put on clean, nonsterile gloves when entering the patient’s room or care area.

- Change gloves in the room if they become torn or heavily contaminated.

- Remove and discard gloves when leaving the patient’s room or care area and immediately perform hand hygiene.

- Gowns

- Put on a clean isolation gown before entering the patient’s room or area. Change the gown if it becomes soiled. Remove and discard the gown in a dedicated container for waste or linen before leaving the patient’s room or care area. Disposable gowns should be discarded after use. Cloth gowns should be laundered after each use.

- If there are shortages of gowns, they should be prioritized for:

- Aerosol-generating procedures;

- Care activities where splashes and sprays are anticipated; and

- High-contact patient care activities that provide opportunities for pathogen transfer to health care workers’ hands and clothing.

Figure 3.1 COVID-19 PPE for health care personnel. Credit: CDC.

Donning PPE

More than one donning method is acceptable. Training and practice using your health care facility’s procedure is critical. Below is one example of donning:

- Identify and gather the proper PPE to don. Ensure a correct choice of gown size.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Put on an isolation gown. Tie all ties on the gown. If needed, request other health care workers assist you with tying the gown.

- Put on an N95 respirator or higher. If the respirator has a nosepiece, it should be fitted to the nose with both hands, not bent or tented. Do not pinch the nosepiece with one hand. The respirator should be extended under the chin, and both your mouth and nose should be protected. Do not wear the respirator under your chin or store it in scrub pockets between patients. The top strap of the respirator should be placed on the crown of head, while the bottom strap should be at the base of the neck. Perform a user seal check each time you put on the respirator.

- Put on a face shield or goggles. When wearing an N95 respirator or a half facepiece elastomeric respirator, select the proper eye protection to ensure that the respirator does not interfere with the correct positioning of the eye protection and that the eye protection does not affect the fit or seal of the respirator. Goggles provide excellent protection for eyes, while face shields provide full face coverage.

- Put on gloves. Gloves should cover the cuff (wrist) of the gown.

- Health care workers can now enter the patient’s room.

Doffing PPE

More than one doffing method is acceptable. Training and practice using your health care facility’s doffing procedure is also critical. Below is one example of doffing.

- Remove gloves. Ensure glove removal does not cause additional contamination of hands. Gloves can be removed using more than one technique (eg, glove-in-glove or bird beak).

- Remove gown. Untie all ties or unsnap all buttons. Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied. Do so gently and avoid any forceful movements. Reach up to the shoulders and carefully pull the gown down and away from the body. Rolling the gown down is an acceptable approach. Dispose of it in a trash receptacle.

- Health care workers can now exit the patient’s room.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Carefully remove the face shield or goggles by grabbing the strap and pulling upwards and away from the head. Do not touch the front of the face shield or goggles.

- Remove and discard the respirator but do not touch the front of it. Start by removing the bottom strap by touching only the strap; bring it carefully over the head. Grasp the top strap and bring it carefully over the head; then, pull the respirator away from the face without touching the front of the respirator.

- Perform hand hygiene after removing the respirator and before putting it on again if your workplace is reusing them.

The following resources cover proper donning and doffing of PPE:

Short supply of PPE

During the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, PPE was in short supply. The following information includes resources of things that can be done when this occurs. It is currently of historical interest but could also become useful in the future.

The NIH 3D Print Exchange provides models for PPE in formats that are readily compatible with 3D printers and offers a unique set of tools to create and share 3D-printable PPE models. These 3D-printable designs are assessed by the Veterans Affairs and the NIH.

ACEP also offers these resources that were collated from member suggestions but cannot vouch for their safety and efficacy:

Existing data and references include:

- Davies A, Thompson KA, Giri K, Kafatos G, Walker J, Bennett A. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013 Aug;7(4):413-418. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.43;

- MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015 Apr 22;5(4):e006577. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577; and

- van der Sande M, Teunis P, Sabel R. Professional and home-made face masks reduce exposure to respiratory infections among the general population. PLoS One. 2008 Jul 9;3(7):e2618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002618.

Reuse of PPE

When adequate supply exists, the CDC recommends that masks not be reused.

The CDC has not approved the routine decontamination and reuse of disposable PPE as the standard of care. However, PPE decontamination and reuse may need to be considered as a crisis-capacity strategy to ensure continued supply availability. Based on limited research, ultraviolet germicidal irradiation, vaporous hydrogen peroxide, and moist heat showed the most promise as potential methods to decontaminate PPE. N95 masks have been reused by individual clinicians. When reusing masks, they should be stored in individual paper bags, cycled over 1 week, and reused up to 5 times. Although suboptimal in terms of hygiene and infection prevention, this method was deemed safer than using surgical masks (which do not remove small particles).

ACEP also offers these resources on reusing respirators. They were collated from member suggestions, and ACEP cannot vouch for their safety and efficacy:

Intubation and aerosolized procedures

Author: Sandra Schneider, MD, FACEP, Senior Vice President for Clinical Affairs, American College of Emergency Physicians; Adjunct Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Pittsburgh

Aerosol-generating procedures are “procedures performed on patients [that] are more likely to generate higher concentrations of infectious respiratory aerosols than coughing, sneezing, talking, or breathing.”1 Although there is no widely accepted, comprehensive list of examples of aerosol-generating procedures, some examples include open suctioning of airways, sputum induction, manual ventilation, endotracheal intubation and extubation, noninvasive ventilation, bronchoscopy, and tracheotomy.2

According to the CDC, if aerosol-generating procedures are performed on a patient with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 or another communicable respiratory disease, the following precautions should be taken:

Endotracheal intubation is an especially hazardous aerosol-generating procedure because droplets are commonly released during both intubation and suction, potentially infecting personnel who perform these procedures.3

PPE provides a level of protection, but placement of a transparent barrier between patients and physicians can provide even further protection from contamination, especially in the emergency department where a patient’s infectious status may not always be known. The CDC has stated that barriers are the best protection from droplets and have suggested the use of plexiglass barriers for clerical workers and in triage.1

The intubation “box,” a popular barrier early in the pandemic, is probably ineffective (Figure 3.2). It is created from transparent material that can quickly be disinfected and formed into a box without a bottom. With cutouts for the neck, it was placed over the head of an unconscious patient, and intubation was performed through two side holes. Although it provides a barrier for large droplets, aerosolized particles are released into the room when the box is removed. There is now evidence that good PPE on staff is superior to these intubation boxes.4-8

Figure 3.2. Prototype and demonstration of an intubation box. Credit: Dr. Hsien Yung Lai.

References

- Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. CDC. Updated May 8, 2023.

- Public Health England. Guidance: COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE). GOV.UK. Updated July 31, 2020.

- Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2020 Jun;75(6):785-799. doi: 10.1111/anae.15054

- Mohr NM, Santos Leon E, Carlson JN, et al; Project COVERED Emergency Department Network. Endotracheal intubation strategy, success, and adverse events among emergency department patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Emerg Med. 2023 Feb;81(2):145-157. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.09.013

- Turer D, Chang J, Banmay H. Intubation boxes: an extra layer of safety or a false sense of security? Stat News. Published May 5, 2020.

- Chan A. Should we use an “aerosol box” for intubation? LITFL. Published July 10, 2020.

- Weech DC, Ashurst J. How to intubate suspected COVID-19 patients with a protective box. ACEP Now. Published on May 19, 2020.

- Simpson JP, Wong DN, Verco L, Carter R, Dzidowski M, Chan PY. Measurement of airborne particle exposure during simulated tracheal intubation using various proposed aerosol containment devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020 Jun 19;75(12):1587-1595. doi:10.1111/anae.15188