ACEP ID:

- My Account

- My CME

- Sign Out

ACEP ID:

Introduction

Residency training prepares learners to deliver excellent patient care. An additional, fundamental topic worthy of investment in both intentional time and education is the knowledge of how emergency medicine physicians receive reimbursement. Just as the healthcare landscape evolves over time, so does reimbursement.

This paper discusses some basics of emergency medicine coding and reimbursement and is designed to provide you, a graduating resident, some key information as you enter independent practice. Although this document is not exhaustive, it will provide the foundation for understanding a topic that will be relevant for your career.

For simplicity, the information has been broken down into two sections:

Section 1: Coding and Documentation

As you triage, resuscitate, and stabilize a patient in the emergency department, it’s vital to document a factual, cohesive, and complete account of the care of that patient. In addition to providing a clinical record to communicate the patient’s course of care, the provided documentation is used to assign specific patient care and procedural codes that reflect the extent of the evaluation and management of the patient, as well as any procedures that may have been performed.

It is important that the documentation be clear and complete, so as to support the codes generated. These codes are used by health care insurers (payers such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance carriers) to determine payment. In most cases, these “payers” do not see any additional information about the encounter. The insurance payer does not receive the actual chart nor do they speak to the patient.

The language of coders is Current Procedural Terminology, or CPT, which has been maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA) since 1966. The AMA CPT Advisory Committee, which consists of representatives from each specialty society, provides guidance to the AMA for annual updates of these codes.

Did you know the specialty of Emergency Medicine is represented by ACEP to the AMA CPT Advisory Committee?

Evaluation and Management (E/M) Coding is the dedicated process by which patient encounters are translated into five-digit CPT codes that are submitted to insurers for payment/ reimbursement. While the CPT manual contains many codes, emergency medicine uses a relatively small number of evaluation and management or E/M codes.

Did you know that 85% of all codes submitted for reimbursement in emergency medicine are E|M Codes?

E/M Codes →→→ CPT Codes

These codes describe the cognitive work and delivery of care that is involved in taking care of the patient. The level of documentation leads to a choice of a specific E/M code. The left-hand column of Table 1 lists some of the codes commonly used for emergency medicine encounters (99281-85). Emergency physicians can also use codes such as 99291 for critical care or Observation codes. There are other codes for specific procedures, which will not be discussed in detail in this basic overview.

But what about ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes?

The International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition, or ICD-10, codes are used to communicate diagnoses to payers. The ICD codes differ from CPT codes in that they are diagnoses codes, whereas the CPT codes reflect the work that was done during the encounter as described above. ICD codes line-up opposite CPT codes on a bill. So, for example, a diagnosis of acute tonsillitis would have an ICD-10 code of J03.90, and perhaps a CPT E/M code of 99283.

Many payers use the diagnosis captured by the ICD codes to determine payment for services. For example, some private payers will not pay above a 99283 for a diagnosis of gastroenteritis. The above point illustrates a violation of the concept of prudent layperson. However, an episode of gastroenteritis that is severe enough to require intravenous fluid resuscitation for dehydration or cause acute kidney injury, may be coded at higher levels if those diagnoses are documented. Therefore, it is important not only to fully document in the chart the work that has been done, but also to carefully list the diagnoses of the problems that have been addressed during the encounter. The Prudent Layperson Standard was a U.S. Congressionally enacted protection passed in 1999, further reinforced with the Affordable Care Act of 2010, that stated that “A medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that a prudent layperson, who possesses an average knowledge of health and medicine, could reasonably expect the absence of immediate medical attention to result in: a) placing the patient’s health in serious jeopardy; b) serious impairment to bodily functions; or c) serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part.” This concept reinforces the separation of final diagnosis and payment and rather payment consists of the work done to establish a medically emergent condition and the care and treatment of that patient.

Are you aware of ACEP’s advocacy efforts on the prudent layperson standard, a key pillar of emergency medicine-delivered care and reimbursement?

2023 E/M Documentation Changes

scored by highest 2 of 3 Components

|

1. Complexity of Problems Addressed (COPA) |

|

2. Data Reviewed and Analyzed |

|

3. Risk of Complications and Morbidity or Mortality |

COMPLEXITY OF PROBLEMS ADDRESSED (COPA)

According to the 2023 CPT Professional Edition, “A problem is a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter, with or without a diagnosis being established at the time of encounter.” The editorial goes further and notes it becomes addressed or managed when it is evaluated or treated at the time of encounter (5). Simply put, just because someone has past medical history indicating diabetes and hypertension does not mean that they are adding to the complexity unless those specific problems are being addressed. For example, consider a patient with past medical history of hypertension and diabetes presenting with signs and symptoms of stroke who is hypertensive requiring intravenous anti-hypertensive medication, or a patient who is being treated for sepsis due to a urinary tract infection with a blood glucose level of 500. As a physician in both scenarios, you would be treating both the stroke as well as the infection, while also addressing the hyperglycemia and hypertension. Be sure to document all comorbidities affecting the presentation, treatment, and clinical plan as this affects the complexity of problem addressed (COPA).

You are required to document a medically appropriate history of present illness and physical exam, although not explicitly required for billing and coding purposes, but you are advised to have a medically appropriate physical exam. Remember that documentation is used for more than billing and coding, but transitions in care as well as medical-legal purposes. Coding professionals can draw from your physical exam to assist in justification of the complexity of the problem addressed. For example, within moderate COPA, there is “acute complicated injury.” Per CPT, this is an injury which requires treatment that includes evaluation of body systems that are not directly part of the injured organ system.

CPT stated that the final diagnosis, in and of itself, does NOT determine the complexity of the problem addressed. The presenting symptoms may “drive” a physician’s medical decision making, irrespective of the final diagnosis (5). This is a shining example of the prudent layperson standard codified within the 2023 documentation guidelines.

This point is worth repeating. The patient’s final diagnosis does not determine E/M code – value is placed on diagnostic/ therapeutic interventions to identify or rule out highly morbid conditions even if ultimate diagnosis is reassuring. One of the finest examples is a patient presenting with chest pain, exertional in nature, associated with diaphoresis. If the workup reveals a reassuring electrocardiogram, cardiac enzyme testing, risk-

stratification, and the final diagnosis is suggestive of GERD as opposed to ACS, you have clinically treated and subsequently documented criteria suggestive for High COPA - illness of injury that poses a threat to life or function (6). Below is a common grid outlining the COPA section in the 2023 Documentation Guidelines.

Conditions that would qualify as AT LEAST MODERATE COPA (not all inclusive):

Conditions that should be considered for HIGH COPA* are patients evaluated with the following (not all inclusive):

*Please note: These do not need to be listed as final diagnosis – evaluating and ruling out these diagnoses indicates High COPA.

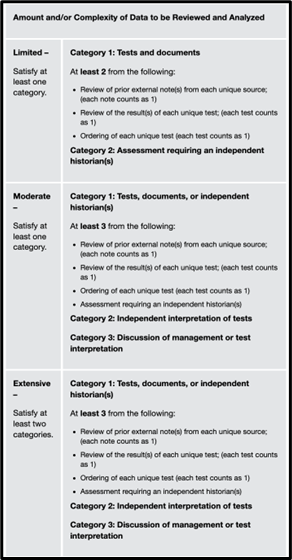

DATA

Data includes three categories:

Category 1: Independent Historian, External Record Review, Review/ Order Tests

Category 2: Independent Interpretation of Tests

Category 3: Discussion of Management or test Interpretation

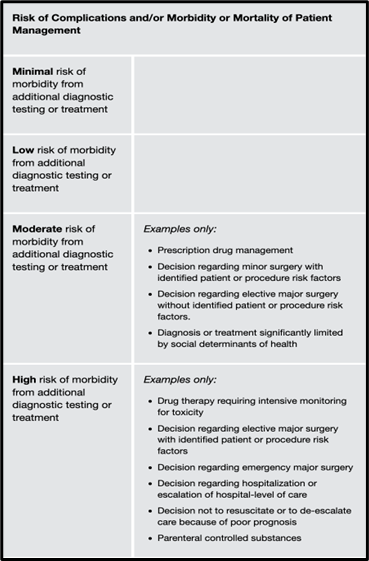

RISK OF COMPLICATIONS AND MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

As you work up patients within the emergency department, different potential levels of risk are present, both affecting a patient’s complications and his or her risk of morbidity and mortality. Two new key categories are present and are worthy of our discussion.

Moderate risk

Prescription Drug Management: review of patient’s medication, start/stop of medication, change in dosage, non-narcotic medication administered within the emergency department. Simply listing the patient’s medication in the record will not satisfy this portion of the risk section.

Social Determinants of Health: Any economic or social condition such as food or housing insecurity that may significantly limit the diagnosis or treatment of a patient’s condition (e.g., inability to afford prescribed medications, unavailability or inaccessibility of healthcare). Common social determinants of health (SDOH) in the emergency department may include homelessness/undomiciled/ housing insecure, unemployed, uninsured, and alcohol or polysubstance abuse.

Did you know that ACEP’s Reimbursement team advocated for the inclusion of social determinants of health (SDOH) to be included as criteria for reimbursement? This was historically important work already being done by emergency physicians which now credit is awarded for addressing.

Recall that your medical record reimbursement is dependent upon the medical decision making and three factors: complexity of problems addressed, data reviewed and analyzed, and risk of complications and morbidity or mortality. It is natural to have questions and we encourage you to review the ACEP Frequently Asked Questions which can be found HERE.

Section 2: Reimbursement and Physician Payment

While in training, residents likely have been exposed to productivity metrics. Residents’ future compensation will be based at least partially on productivity. The basic element used to measure this productivity is known as the Relative Value Unit (RVU) and it is based on physician effort, training, and other factors.

An RVU is the universal metric of physician effort and the building block of payment.

Each E/M and procedure code is assigned a certain number of RVUs through a specific process. The Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) is composed of representatives from each specialty and makes recommendations on the value of codes to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the Medicare Fee Schedule.

Did you know that Emergency Medicine is represented by ACEP at the AMA RUC?

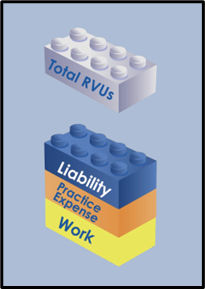

The RUC uses the Resource Based Relative Value Scale, or RBRVS, to rank services relative to other services in a budget neutral manner. The RVU has multiple components as illustrated in Figure 1.

Physician work captures both the cognitive and procedural work performed by the physician. The work RVU makes up approximately 72% of the total RVU. The work RVUs are reviewed approximately every five years. The E/M codes used in Emergency Medicine (99281-99285) were reviewed in 2021 for the 2023 Medicare physician fee schedule. The practice expense RVU is designed to factor in the cost of coding, billing, and collections, as well as the cost of payroll and support staff. There is also a component that covers liability insurance. The national breakdown by percentage of E|M codes for 2022:

99281: 1%

99282: 2%

99283: 12%

99284: 30%

99285: 40%

99291: 4%

Figure 1. RVU Components

Physician Work + Practice Expense (facility) + Liability Insurance (malpractice) = Total RVU

There is also a Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) that reflects the cost differential in practice based on location. Each RVU component listed above is adjusted based on the local cost index. Once the total RVU is determined, it is then multiplied by the Medicare conversion factor (CF), to determine the final payment. The final 2024 Medicare conversion factor after Congressional adjustment for physicians is $33.2875, a $0.60 decrease or 1.69 percent decrease from $33.89 in 2023.

Many emergency physicians productivity will be determined by a formula such as:

RVU/Hour = RVU/patient x Patients/hour

A simplified version of reimbursement is:

E|M CODES → RVU → *Conversion Factor

* Conversion Factor is a Medicare-derived number set from a complex formula taking account of the U.S. economy, changes in government spending for healthcare services, and previous conversion factor. In addition, U.S. Congressional action can impact the CF.

RVU increases with each E|M Level

Table 1: Complexity of MDM

|

|

MDM Complexity |

Number of Diagnosis and Management Options |

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Review |

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity and Mortality |

|

99281 |

|

|

|

|

|

99282 |

Straight forward |

Minimal |

Minimal or None |

Minimal |

|

99283 |

Low Complexity |

Limited |

Limited |

Low |

|

99284 |

Moderate Complexity |

Multiple |

Moderate |

Moderate

|

|

99285 |

High Complexity |

Extensive |

Extensive |

High |

Table 2: Current 2023 RVUs for E/M Codes

|

Code |

Description |

Work RVU |

Facility RVU |

MP RVU |

2023 Total RVUs |

|

99281 |

ED Visit |

0.25 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

0.35 |

|

99282 |

ED Visit |

0.93 |

0.21 |

0.10 |

1.24 |

|

99283 |

ED Visit |

1.60 |

0.35 |

0.18 |

2.13 |

|

99284 |

ED Visit |

2.74 |

0.57 |

0.27 |

3.58 |

|

99285 |

ED Visit |

4.00 |

0.79 |

0.42 |

5.21 |

|

99291 |

Critical care 1st hour |

4.50 |

1.39 |

0.42 |

6.31 |

|

99292 |

Critical care add’l 30 min |

2.25 |

0.70 |

0.22 |

3.17 |

Example:

Level 5 RVU x Medicare 2024 CF = Total Physician Payment

5.21 x $33.29 = $173.44

Section 3: Procedures and Critical Care

Most of the RVU’s and subsequent reimbursement in emergency medicine are 99281-99285. However, there are additional items that comprise reimbursement within our speciality. Procedures make up 9% of the total while critical care performed makes 8% of the total. Thorough and complete documentation makes the difference when it comes to appropriate billing and subsequent reimbursement. Please see below for common procedures that emergency physicians perform.

Table 3: Procedure RVUs

Note the difference in RVUs in the above chart and consider a daily emergency department shift and the procedures you perform. One common procedure performed in emergency departments is laceration repairs. The documentation factors required are: location, length, layers, and foreign material. Be sure to measure the laceration. If you perform undermining to allow the skin to approximate more appropriately, document it. If you performed an incision and drainage and probed the wound for loculations, document. It is considered a higher level of RVU and documenting these within your procedure note for appropriate reimbursement.

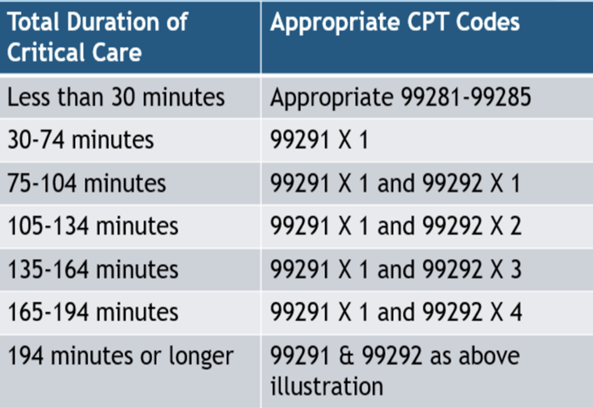

Critical Care is defined as an illness or injury that:

Critical care is codified as 99291 and 99292 depending on the length of time. Critical care must have at least 30 minutes of service spent directly managing, resuscitating a patient who is unstable or potentially unstable. Please refer to Table 2 for more information regarding the 2023 RVU allocation. The time does not have to be continuous to count towards critical care. Time spent documenting, reviewing labs and radiographs, and speaking with medical staff also counts towards total critical care time. Time spent on separately billable procedures, like CPR (92950), doesn't (1). You must have provided at least 30 minutes of services to bill. Additional time increments over the initial 74 minutes are billed with 99292 for each additional 15-30 minute segment. Some procedures are “bundled” within critical care meaning you cannot separately bill for it.

The bundled codes are included in the list below:

Any procedures not on this list can be billed separately, and the time spent performing additionally billed procedures must be deducted from Critical Care time and indicated in the record. A statement such as "Critical care time spent in direct management of this patient was 75 minutes exclusive of separately billed procedures" is recommended (1). For more information on critical care documentation, please refer here.

Table 5. Critical Care Documentation

A Tip for Documenting on Your Next Shift: Macros

When using an electronic medical record, it is common for a physician to use a macro for some portions of the documentation required for a patients visit. Providers should ensure that any information contained in a macro is appropriate for the patient being seen and accurately reflects the work done. Make sure each chart is unique. The EMR should contain patient specific information that is sufficient to support the medical necessity of the service provided. Beware that casual use of macros can lead to errors in documentation such as “LMP normal” in a male or “No focal neuro deficit” in a patient seen for chest pain but whose exam reveals extremity weakness from a prior stroke.

Shared Visits

Advanced Practice Practitioners (APP’s), also called Non-Physician Practitioners (NPP) by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid, are Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners. Both professions play a unique and valued role within emergency medicine. Per CMS guidelines, NPPs are at 85% of the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (7). When the emergency physician and the NPP share in the care of a patient (i.e. performance of the E&M service), it is allowed to be reimbursed at 100% of the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, only if the physician performs the substantive portion of the care of the patient. Thus, recall our discussion of the components of reimbursement for the emergency physician and the 2023 documentation guideline updates. The physician must perform the substantive portion of the visit (i.e., MDM components) for appropriate reimbursement.

Top 15 Tips Regarding Documentation, RVUs, and Reimbursement

Conclusion

This paper is designed to give the graduating resident an overview of the basics of emergency physician reimbursement. Further information is available through a variety of sources including the ACEP website: ACEP Reimbursement FAQs. The website has nearly 40 Frequently Asked Question sets on emergency medicine coding and reimbursement topics and guidance on compliance and documentation issues.

Updated: January 2024

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Mr. David McKenzie, Jeffrey Davis, and Adam Krushinskie for their wisdom and guidance. Thank you to Dr. Nicholas Cozzi, Dr. Jamie Shoemaker, Dr. Michael Granovsky, Dr. Steve Kailes, Dr. Bryan Graham, Dr. Lisa Maurer, Dr. Alexa Golden, Dr. Brian Hiestand, Dr. Becky Parker, and Mr. Todd Thomas for expert consultation as this resource was created. Special thanks to ACEP’s Reimbursement Committee and Coding and Nomenclature Advisory Committees as well as Mr. Ed Gaines.