September 2, 2020

GI - Bowel Obstruction

Thompson Kehrl, MD, FACEP

Casey Wilson, MD

I. Introduction

- Prevalence: approximately 2% of all ED patients with abdominal pain will be diagnosed with a small bowel obstruction (SBO).1

- Overall SBO ultrasound (US) has high sensitivity (92.4% with 95% CI 89.0% to 94.7%) and specificity (96.6% with 95% CI 88.4% to 99.1%) with associated +LR of 27.5 (95% CI 7.7 to 98.4) and -LR of 0.08 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.11).2 It consistently outperforms X-ray, and has similar diagnostic accuracy to computed tomography (CT).

- Bowel ultrasound goes beyond just identifying obstruction. Other applications include diagnosing intussusception, appendicitis, pneumoperitoneum, gastrostomy tube placement, fecal burden, upper GI bleed, esophageal food impactions, and more.3-7

II. Anatomy

- Small bowel is approximately 6.5 meters in length in the average person, extending from the pylorus of the stomach to the ileocecal junction, and is divided into three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. There is no clear anatomic division between the jejunum and ileum.8

- Small bowel contains circular folds (plicae circulars or valves of Keckring). These folds are very prominent in the jejunum and taper off in their distribution in the ileum, with few if any folds present in the distal ileum. Compared to the haustra of the large bowel, plicae circularis are much closer together and run the entire circumference of the small bowel.9

III. Scanning Techniques, Normal Findings, and Common Variants

- A large-footprint curvilinear 3.5-5 mHz probe is appropriate for larger adult patients. A higher frequency probe may be more optimal for pediatric or thin adult patients.

- The patient should be comfortable and in a supine position to relax the abdominal wall and apply gentle pressure.

- The entire abdomen should be scanned in sagittal and transverse planes using the “lawn mower technique,” including all four quadrants and the epigastrium.10 Bowel loops should be visualized in each region and assessed with regards to diameter, wall thickness, and peristalsis.

- Normal findings: Normal bowel should be filled with digestive contents and air. Normal peristalsis is generally unidirectional and extra-luminal fluid should be absent. Normal adult bowel wall thickness is typically </= 3mm and </= 2 mm when distended.11

- Video 1. Normal bowel

- Particular efforts should be taken to visualize the stomach (LUQ/epigastrium) and the terminal ileum (RLQ), as this can reveal obstruction at the gastric outlet or ileocecal junction.

- The sonologist should also evaluate for intra-abdominal free fluid interspersed between loops of bowel and in typical locations such as Morison’s pouch.

IV. Pathology

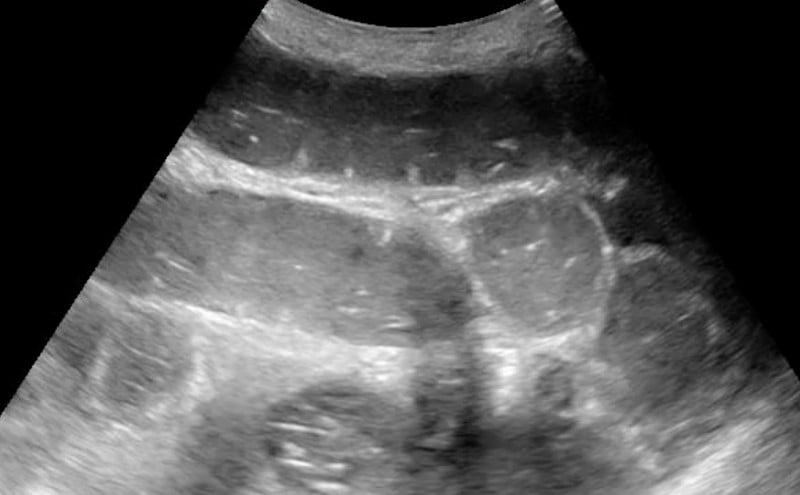

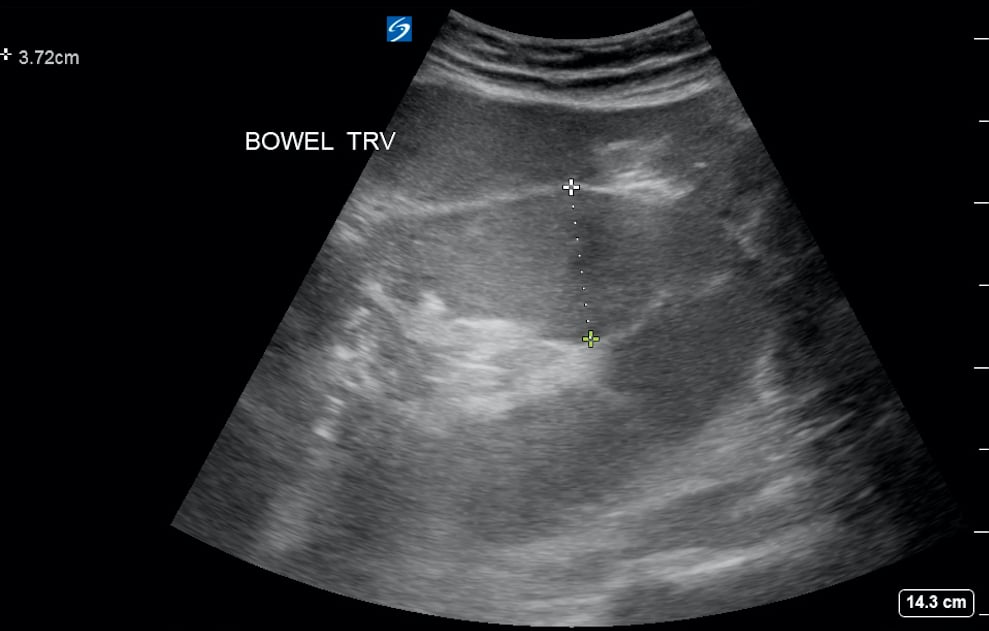

- The diagnosis of SBO is additive. Pathologic findings include dilation of small bowel > 2.5 cm (see Fig. 1), abnormal (“to and fro”) peristalsis (see Video 2), bowel wall thickening, and the presence of extraluminal free fluid between loops of bowel (see Video 3).

- Figure 1. Significantly dilated loop of small bowel. Also note free fluid interposed between loops of bowel (white arrow).

- Video 2a. Abnormal “to and fro” peristalsis in SBO

- Video 2b. Abnormal “to and fro” peristalsis in SBO

- Video 2c. Abnormal “to and fro” peristalsis in SBO

- Video 3a. SBO with interposed free fluid (dashed arrows)

- Video 3b. Extraluminal free fluid in SBO

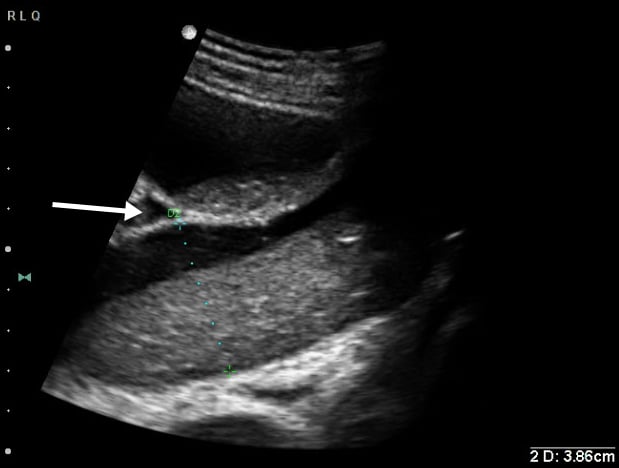

- The identification of a transition point between proximal distended, fluid-filled bowel and distal decompressed bowel is pathognomonic for small bowel obstruction but can be difficult to locate sonographically.12

- If dilated, fluid-filled bowel is identified, the probe should be rotated to visualize the segment in a longitudinal axis and assess peristalsis. Abnormal peristalsis in SBO is generally described as “to-and-fro” with a shuttling or swirling appearance to the luminal contents.

- The small bowel can be identified by visualizing the plicae circularis. Bowel wall edema in SBO can accentuate these structures, creating the “piano key sign” or “keyboard sign.” Of note, the analogous haustra of the large intestine are sparser and spaced much further apart.

- Video 4a. Jejunal keyboarding in a patient with a SBO

- Video 4b. SBO with “piano key sign”

- Free fluid interposed between loops of bowel suggests higher grade SBO and makes the need for surgical intervention more likely.13

- Of the different sonographic findings in SBO, bowel dilation has the highest specificity and abnormal bowel peristalsis has the highest sensitivity.14

V. Pearls and Pitfalls

- Tips

- Bypass bowel gas by looking laterally or using graded compression

- Be wary of gastric bypass patients

- LUQ views can help identify gastric outlet obstruction without distal SBO; image the LUQ where a distended stomach without peristalsis suggests the former.

- Video 5. Dilated stomach in gastric outlet obstruction

- To distinguish between SBO and LBO, try to identify the haustra that characterize large bowel. Large bowel also typically has a larger diameter than small bowel, up to 4-5 cm, and often massively dilated in obstruction.15

- Common mistakes

- Mistaking gastroenteritis for SBO: In gastroenteritis, bowel loops can be fluid filled, but are not typically dilated. Peristalsis may be increased but remains unidirectional.

- Mistaking an ileus as SBO: Distinguishing between the two can be difficult. Fluid filled, distended loops of bowel can be seen with ileus, but peristalsis may be reduced. Clinical correlation is key.?

- Video 6a. Ultrasound image of ileus (diagnosed on CT). Note fluid filled loops of bowel with somewhat decreased but still present peristalsis. Bowel is not significantly distended.

- Video 6b. Ileus

- Diarrheal states will often consist of fluid filled loops that can mimic SBO but bowel loops will often be normal size and have normal peristalsis.

- Video 7. Diarrheal state

- SBO US often cannot routinely distinguish the cause of SBO, unless clinically evident.

- Video 8. Incarcerated hernia as transition point in SBO

- Video 9. Increased bowel wall thickness and diameter in SBO

- Video 10. SBO with dilated small bowel loops and subtle “to and fro” movement of bowel contents

- Figure 2. Dilated small bowel in setting of SBO

VI. References

- Taylor MR, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528-44.

- Gottlieb M, Peksa GD, Pandurangadu AV, et al. Utilization of ultrasound for the evaluation of small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(2):234-42.

- Zhou AZ, Toporowski A, Tsung JW. Sonographic evaluation and monitoring of pneumoperitoneum after air enema reduction for intussusception. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Jul;35(7):e133-e134.

- Shahbazipar M, Seyedhosseini J, Vahidi E, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound exam performed by emergency medicine versus radiology residents in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2019 Aug;26(4):272-276.

- Myatt TC, Medak AJ, Lam SHF. Use of point-of-care ultrasound to guide pediatric gastrostomy tube replacement in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(2):145-8.

- Yabunaka K, Matsumoto M, Yoshida M, et al. Assessment of rectal feces storage condition by a point-of-care pocket-size ultrasound device for healthy adult subjects: A preliminary study. Drug Discov Ther. 2018;12(1):42-6.

- Singleton J, Schafer JM, Hinson JS, et al. Bedside sonography for the diagnosis of esophageal food impaction. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(5):720-4.

- The Small Intestine. Source: The Teach Me Series. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Circular Folds. Source: Wikipedia. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Atkinson NSS, Bryant RV, Dong Y, et al. How to perform gastrointestinal ultrasound: Anatomy and normal findings. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Oct 14;23(38):6931-41.

- Wale A, Pilcher J. Current role of ultrasound in small bowel imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2016;37(4):301-12.

- Pourmond A, Dimbil U, Drake A, et al. The accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound in detecting small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med Int. 2018;3684081.

- Grassi R, Romano S, D’Amario F, et al. The relevance of free fluid between intestinal loops detected by sonography in the clinical assessment of small bowel obstruction in adults. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(1):5-14.

- Barzegari H, Delirooyfard A, Moatamedfar A, et al. A new point of care ultrasound in disposition of patients with small bowel obstruction in emergency department. Intern J Pharm Res Allied Sci. 2016;5(2):200-7.

- Hollenweger A, Wustner M, Dirks K. Bowel obstruction: Sonographic evaluation. Ultrashall Med. 2015;36(3):216-38.