Mastering the Intussusception Ultrasound - Tips and Tricks

EUS Section Pediatric EM Subcommittee

Introduction

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children less than 2 years of age. While it should be considered in older children as well, 80-90% of cases occur in children younger than 2 years.1 It occurs when a segment of bowel telescopes into another segment of bowel, and most often occurs at the ileocecal junction. As intussusception develops, the mesentery is dragged into the bowel which leads to venous and lymphatic congestion and ultimately leads to ischemia, perforation, and peritonitis if untreated. While lead points such as lymphoid hyperplasia, polyps, and tumors are sometimes identified, these account for only about 25% of cases. The majority of cases in children are idiopathic.2

The presentation of intussusception can be variable and age dependent. Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom but can be difficult to interpret in younger non-verbal children. Vomiting is also common across age groups. Classically, intermittent episodes of screaming and abdominal pain are described with a drawing up of the knees towards the chest. Mental status changes have also been described as alternating periods of lethargy and irritability. Bilious vomiting and lower gastrointestinal bleeding are late findings with the classic ‘currant jelly’ stools occurring in less than 50% of cases. Occasionally, a sausage-shaped mass may be palpated in the right upper quadrant, but this is appreciated in less than a third of patients.1

Ultrasound Imaging for Diagnosis

While X-rays may be helpful to evaluate for the presence of intussusception, ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice. In experienced hands, ultrasonography has excellent test characteristics with both sensitivity and specificity of >97% and a negative predictive value of 99.7%.3 At the bedside, pediatric emergency physicians with limited and focused training are also able to accurately diagnose ileocolic intussusception with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 97%.4

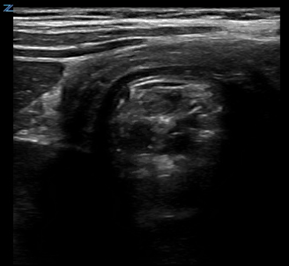

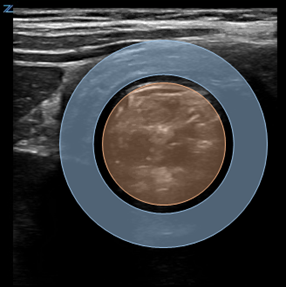

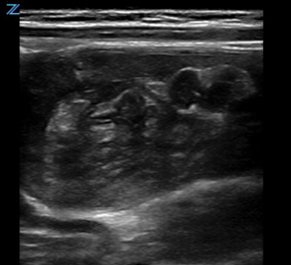

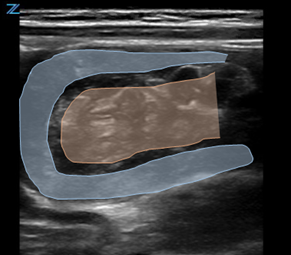

Classically, intussusception manifests in the transverse orientation as a ‘target sign’ or ‘donut sign’ (Figure 1) representing layers of intestine within the intestine. In the longitudinal orientation, the layers of intestine appear as a ‘pitchfork’ or ‘submarine sandwich’ (Figure 2). These findings are most commonly seen in the right lower quadrant for ileocolic intussusception, which is the most common type of intussusception. Small bowel intussusceptions can be differentiated by their size, which are often ≤3 cm.5 While small bowel intussusceptions often spontaneously reduce, if symptoms and findings persist, computed tomography (CT) may be necessary to determine management. POCUS is useful in differentiating variants of intussusception that range from a surgical emergency to a transient source of abdominal pain allowing clinicians to better manage these patients.6

Technique

- Prepare your patient!

- These children may be fussy - enlist the parents to help comfort and distract

- Use warm gel

- Position your patient supine - may be best on parent’s lap

- Use a high frequency linear probe (7.5 – 10 MHz)

- Start in the right lower quadrant to scan.

- Scanning pattern -

- Picture frame pattern (Figure 3) - hold the probe in transverse to scan from RLQ to RUQ, sagittal to scan from RUQ to LUQ, and then rotate back to transverse to scan from LUQ to LLQ

- Lawnmower pattern (Figure 4)- hold the probe in transverse orientation and scan up and down from left to right across the patient's abdomen

- Ensure that your depth is adequate (approximately 5-6cm depth to start)

- Use graded compression to push bowel gas out of the way

- Scanning pattern -

- Once the intussusception is identified, measure the diameter to differentiate between small bowel or ileocolic intussusception ( >3cm likely ileocolic)

- Prognosticate with color Doppler and assess for free fluid.

- Add color Doppler to look for ischemia and assess for decreased perfusion and bowel infarction.

- Free fluid in the abdomen can suggest late stage of disease.

Limitations

Some processes that cause bowel wall thickening such as infectious or inflammatory colitis can be misinterpreted for multiple layers of bowel wall seen in intussusception. Intermittent intussusception can be missed if it self-reduces before the scan. An operator that does not adequately adjust their depth or systematically scan the abdomen may miss an intussusception.

Take Home Points

- Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children under 2 years of age and should be on the differential for any fussy baby without an obvious source.

- Set up for Success! Enlist the parents to help distract and comfort, and use warm gel for your scan.

- Look out for a target sign or pitchfork sign indicating layers of bowel inside bowel.

- Repeat ultrasound in patients you have a high clinical suspicion for intussusception, especially if the patient has an active episode of crying and abdominal pain.

Figure 1. Target Sign on cross-sectional image of intussusception

Figure 2. Pitchfork Sign on longitudinal image of intussusception

Figure 3. Picture frame pattern to scan the abdomen. In 1 and 3 above your probe should be in the transverse orientation with the marker pointing towards the patient’s right. In 2 above, the prove marker should be in the sagittal orientation with the marker pointing towards the patient’s head

Figure 4. Lawnmower pattern to scan the abdomen. In this scanning pattern, the probe stays in the transverse orientation with the probe marker remaining towards the patient's right side.

References

- Mandeville K, Chien M, Willyerd FA, et al. Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(9):842-4. PMID: 22929138.

- Ntoulia A, Tharakan SJ, Reid JR, et al. Failed intussusception reduction in children: correlation between radiologic, surgical, and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(2):424-33. PMID: 27224637.

- Hryhorczuk AL, Strouse PJ. Validation of US as a first-line diagnostic test for assessment of pediatric ileocolic intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(10):1075-9. PMID: 19657636.

- Riera A, Hsiao AL, Langhan ML, et al. Diagnosis of intussusception by physician novice sonographers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):264-8. PMID: 22424652

- Ko SF, Tiao MM, Hsieh CS, et al. Pediatric small bowel intussusception disease: feasibility of screening for surgery with early computed tomographic evaluation. Surgery. 2010;147(4):521-8. PMID: 20004447.

- Park BL, Rabiner JE, Tsung JW. Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of small bowel-small bowel vs. ileocolic intussusception. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1746-50. PMID: 31257125.

Lorraine K. Ng, MD

Associate Professor, Asst Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York

Maytal Firnberg, MD

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York