Exercising the First Year Efforts of a Regional Disaster Health System Pilot Grant

In the early summer of 2018, the US Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) released a funding opportunity announcement for a new program designed “to better identify and address gaps in coordinated patient care during disasters through the establishment and maturation of a Regional Disaster Health Response System (RDHRS).” As defined by the FOA, the primary objectives of the RDHRS program are “to: 1) improve bidirectional communication and situational awareness of the medical needs and issues of the response between healthcare organizations and local, state, regional, and federal partners, 2) leverage, build, or augment the highly specialized clinical capabilities critical to unusual hazards or catastrophic events, and 3) augment the horizontal (whole of community) integration of key stakeholders that comprise healthcare coalitions with readily accessible and clinical capabilities that are largely missing from the current configuration of such coalitions.” In the first year of the pilot projects, recipients are asked to ensure whole-of-state coordination of highly complex clinical care in disasters; in future years the pilot sites will expand their lessons learned to become multi-state regional collaborations capable of coordinating patient care and transfers across state lines.

In September 2018, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Nebraska Medicine were notified that they had been selected as the initial participants in this pilot program to build regional partnerships, develop plans and policies of excellence, improve local and regional patient capacity in the event of a disaster, improve situational awareness and develop metrics to test the system’s readiness. The “Massachusetts/Region 1 Partnership for Regional Disaster Health Response” was thus created, and the Massachusetts/New England program convened all 8 of the tertiary care hospitals of Massachusetts, the state department of public health, the state emergency management agency, all of the healthcare coalitions in the state, all of the EMS regional directors in the state, the American Burn Association (ABA), and several others including public health emergency preparedness leaders from the other New England States to work on these challenges of medical disaster response.

The Partnership started the grant year by polling its members and others to identify and prioritize work on perceived gaps in clinical disaster care and response systems. The top three gaps identified in this work were 1) improving coordination of healthcare system surge planning across the state and region, particularly for specialized clinical scenarios involving surge in trauma, burn, pediatric, or other special types of victims, 2) creating a system that can provide public health and emergency management leaders with specialized medical and technical expertise related to patient movement and care during disasters, and 3) improving the Essential Elements of Information (EEIs) related to medical care and healthcare operations that are used by local, state, regional and federal partners to monitor and manage response. In response to these gaps, the Partnership identified three main goals for its first year of work, which included building a network of technical disaster medical advisors from participating tertiary health care institutions to improve the medical and healthcare system operational planning and expertise in support of patient care and resource movement during disasters, establishing a 24/7/365 deployable center with integrated disaster medical expertise to support incident response and medical situational awareness, and developing rapidly deployable general and specialty medical response teams that can support local, state and regional efforts during these events. The Partnership has also convened a subset of stakeholders to suggest improvements to EEIs used in disasters and is coordinating this work with the team at Nebraska Medicine to minimize conflicts or gaps.

Over the past 10 months, the MA/Region-1 Partnership team has convened many different stakeholder groups and response partners in meetings, workshops, and other venues to work towards the goals above, and has developed a variety of different plans, protocols, tools, ideas, and other products. On August 27, 2019, the Partnership conducted its first test of its efforts through a statewide functional exercise.

The functional exercise started with the scenario of a large burn event similar to the 2015 Taipei water park explosion at a fictional 30,000-person family music festival where the propane tanks of adjacent food trucks exploded as well. The fictional disaster created more than 1,500 injuries to adults and children, who had burns, penetrating trauma, blunt trauma from trampling, and other injuries. More than 450 of the patients were critically injured and required care in the state’s trauma centers, burn centers, and pediatric specialty hospitals. However, following the disaster epidemiology of other historic disasters, many of the exercise patients self-evacuated or were taken by private vehicles, ride share services, law enforcement, and EMS first to nearby community hospitals and other facilities, and needed subsequent transfer to the specialized clinical centers.

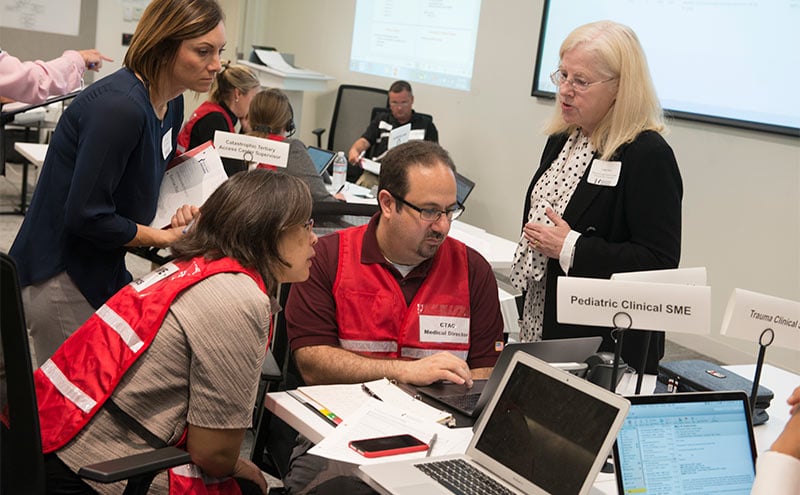

In response to the simulated mass casualty disaster, the MA Partnership activated its newly developed RDHRS Response Center (RC) and several associated new plans during the exercise. The RDHRS RC activated a Catastrophic Tertiary Access Center (CTAC), which centrally managed and coordinated all of the interfacility transfers from community hospitals using a single point of access to direct the patients equitably using clinical capability and capacity criteria to the available trauma, burn, and pediatric hospitals. The CTAC was staffed with a disaster-trained medical director and advised by trauma, burn, and pediatric experts, as well as by a number of patient placement expert nurses and admitting staff all drawn from the member RDHRS hospitals. Using specially developed technologies for the RDHRS, the CTAC established communication with the RDHRS receiving hospitals through a Capacity Management Coordinator (CMC), who helped the CTAC identify and continuously monitor appropriate capacity and capability in the system in real-time and direct patient movement appropriately. The CTAC burn specialist also actively coordinated with the Regional and National ABA resources to augment the burn expertise and resources available to the Massachusetts response. These activities of the CTAC directly addressed the identified gaps of expert clinical involvement in the medical response and decision-making, as well as in the coordination of patient movement and care in a wide range of facilities with differing specialty capabilities and capacities to accept patients.

The RDHRS also activated a telemedicine center which connected community emergency department physicians with trauma and burn specialists as they managed the critically ill patients in their care while awaiting transfer. For the exercise, the telemedicine efforts were tested with use of hospital simulation centers remote from the RDHRS RC. Lastly, the RDHRS RC also tested its activation processes to utilize a state or regional-deployable disaster medical team to assist the overwhelmed local emergency departments in the care of the lesser-injured patients over the first 12-24 hours following the event.

Overall, the exercise was extremely successful in demonstrating the potential value of an RDHRS. The RDHRS was able to utilize specialized disaster medical experts to guide and support the healthcare system response and the use of specialized clinical resources in real time. In addition, the CTAC was highly effective in streamlining and coordinating disaster patient interfacility transfers across the entire system, guiding patients to the most appropriate available specialized medical centers quickly by using technology and a common, coordinated healthcare system approach spanning the entire state. When the exercise scenario presented a volume of burn and pediatric patients far exceeding the capacity of the local specialty tertiary care centers, the RDHRS expert clinicians successfully determined how the state’s burn, trauma, and pediatric specialty beds and other resources would coordinate most effectively in real time to save the most lives and produce the best outcomes. Further, the RDHRS was later able to coordinate with the ABA’s Regional burn center to support national-level tertiary patient redistribution once additional burn beds outside of the area were identified in the exercise. In future years, the plans and tools being developed for the RDHRS should be very well-suited to supporting a multi-state regional approach to healthcare system disaster response. By engaging the tertiary care and other specialized hospitals across an entire region, future RDHRS programs will be able to expand their pool of available clinical experts who can participate in response, as well as to engage more specialized facilities with more capabilities and more capacity in this more coordinated disaster healthcare response system. The common technologies, plans, and protocols being developed within the RDHRS system will allow greater collaboration and coordination by healthcare disaster responders themselves across a larger region, and will help to ensure that all of the region’s healthcare capabilities and capacity is most effectively used in response to disaster.

Needless to say, there were also many lessons learned that identified areas for improvement that will be important as the initial draft programs, procedures, and systems that have been developed in the first year of the RDHRS program are formalized, implemented, and integrated with all the appropriate response agencies and partners in the state and Region. In the coming months, both the Massachusetts and the Nebraska RDHRS programs will have the chance to review their initial year’s work, review the results of their first exercises testing the systems, and to continue to speak with local, state, regional, and federal stakeholders and partners and further refine the best roles, capabilities, and plans for an RDHRS entity. In preparation for the next funding year, the RDHRS sites are also investigating the best ways to translate and apply their lessons learned in neighboring states in order to achieve the vision for multi-state regional capability and capacity articulated by the RDHRS program.

Paul D. Biddinger, MD, FACEP