An Ethical Basis for Building Resilience by Education and Communication in a Catastrophic Biologic Event

Part 2 of a Continuing Dialogue

“FEMA will not save you,” said Michael Brown, former director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, at the National Press Club 21 June 2011. The government will not always be there, Brown warned. “There needs to be an understanding of the role of government and the role of the individual,” he said. “It is the individual’s responsibility to be prepared for disasters,” he said. “People need to be prepared to take care of themselves,”

“Government officials consistently warn Americans to be prepared but the American people ignore warnings from government officials because they don’t want to think about disasters happening,” Brown said. “We become very complacent and comfortable with the way we live. We have a belief that we are Americans and nothing bad can happen to us.”

Nothing has affected our society more than the pandemic of 1918 and we do not know how another event of this magnitude in today’s society will affect our population. We surmise it will affect all levels of society and the economy. It will affect interpersonal and governmental relationships and will respect no boundaries. It will begin locally, continue as a local event, and end locally.

So how do we build community resilience? Resilience is born of independence and self-reliance. It is a dynamic process by which positive behavioral adaptation occurs in spite of significant adverse events, real or perceived. It is the ability to cope with stress in a healthy manner, holding the belief that something can be done about the situation, feeling like a survivor, learning from the past, and holding a positive outlook for the future. Resilience in not inbred, but rather a learned pattern of behaviors.

Among the problems facing planners today is the fact we live in a socially fragmented society, geopolitically isolated, ethnically intolerant, with many religious beliefs, and with an innate fear of government intervention. We have variable education levels in our communities and multiple languages spoken within and outside the family unit. Family units may be a single parent household or blended family, or a community of the homeless. Each will have variable ways to obtain communication from the outside world. Most have no reserves, living paycheck to paycheck, with only a few days’ supply of food, water, or medication available if systems fail.

Most States like Texas are comprised of an amalgam of counties, special interest districts, home rule cities, general rule cities, each with limited responsibility one to another. Due to the diversity, there is no standardized approach to First Response or Healthcare.

The truth of the matter is that the threats are real but often not perceived. Our economy is based on “just in time production” without any reserve. We operate at maximum surge most of the time. Fiscal responsibilities determine the maximum workforce and supplies. The workforce may be so affected by an event as to limit the production capacity of the population. And, any deficit in the supply chain will cause resources to be scarce.

Communities need to be working on and continuing to review a sustainable plan and mitigation actions to ensure continuity of community services and maintain the supply chain. Plans must be innovative in managing the impending/worsening catastrophic event. By developing plans now and maintaining surveillance, time is saved when disaster occurs. Delays in providing services results in needless anxieties and suffering for individuals and families affected as well as placing additional burden on responders. Effective planning leads to timely and effective disaster relief operations.

Authorities must have the public’s trust. Communications must therefore be open, non-distorted or manipulated. Messages and actions must be consistent across jurisdictions, among agencies and organizations, and assure a coordinated and effective response. There must be a social media monitoring strategy to circumvent prejudicial and conflicting stories.

Communications for responders and the public must emphasize personal preparedness. It must create a sense of self-reliance to prevent infrastructure overload and prevent economic collapse. Messages need be preplanned with special consideration given to language barriers, religion and cultural beliefs, educational level, single parent and blended families, ethnicity, and the homeless and impaired. There must be a phased approach to communication consistent with the situation in real time.

Intense media coverage and public interest will provide opportunities and challenges. Effective public communications and risk communication should empower the public to respond appropriately, to protect themselves and care for each other. Education must emphasize the ME, the WE, and the THEY. The individual is his/her own first responder. Emphasize you must be able to protect your family /team before you can take care of everyone else. The plan must be available and practiced in advance of the event. It is important to have someone to discuss the issues with and look out for you. Therefore, you need a Disaster Buddy.

Resources may be less than optimal. It therefore behooves us to have a tiered scalable framework for scarce resource allocation. It must provide guidelines and policy implemented on a regional basis, with liability protections, applied equally to all, implemented in a stepwise fashion, based on objective criteria (modification from Hick and O’Laughlin, Academic Emergency Medicine 2006 13:223-229). Triage protocols will then be used to guide resource allocation. Such a plan will equitably provide every person the opportunity to survive, but not guarantee either treatment or survival (Christian et al, Ontario, Canada).

Ethical considerations involved in the allocation of scarce resources revolve around:

Duty to Care: There is a fundamental obligation to care, but population care may take precedent to personal care.

Duty to Steward Resources: The balance to save the greatest number of lives must be weighed against the obligation to care for each individual.

Duty to Plan: Failure to plan amounts to a failure of responsibility.

Distributive Justice: Collaborative agreements should be completed to pool scarce resources and alleviate shortages.

Transparency: The plan must be open and available to all extent possible inclusive of educating responders and the general public.

Preserving the function of society will receive the greatest priority. Those individuals essential to the provision of healthcare, public safety, and the functioning of key aspects of society should receive priority in the distribution of scarce resources. They are involved in the day to day operations responsible for the maintenance of basic societal functions. This Social Worth criterion is only justified under these limited circumstances

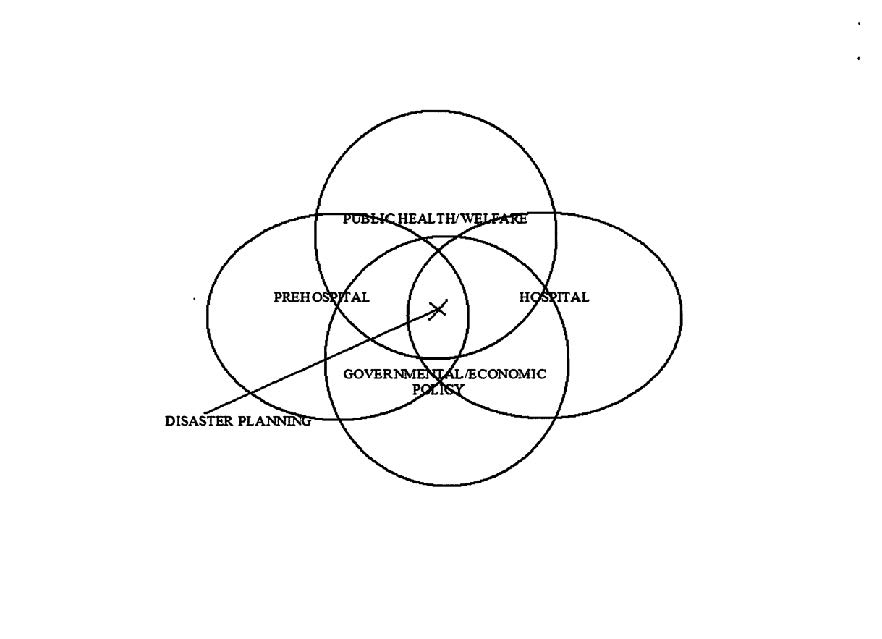

There is an intimate relationship between service sectors representing Public Health and Welfare, Government and Economic Policy, Hospital Agencies, and Pre-Hospital Emergency services. Their intersection representing Disaster/Emergency Preparedness and Prevention.

An efficient and effective disaster response system encourages multi-organizational participation and preparation, cooperating with all entities, agencies, and organizations, embracing all aspects of the critical infrastructure and key resources of the community.

We need to develop a culture of awareness where cooperation between entities is essential. Support of integrated plans between agencies and providers is essential, with cross sectoral training and shared resources and personnel.

No one really knows how things will work when critical resources (equipment/supplies) run out, staffing is down to a fraction of normal, critical systems fail, or healthcare becomes diminished or inaccessible. Large segments of the population may become mobile looking for assistance (mass migration). The system may become overwhelmed by potentially infected individuals or contaminated human remains or cannot care for estranged or ill animals and have to deal with accumulated carcasses.

Today, we have a resurgence of measles in the Americas, Europe, and the former republics of the Soviet Union. Ebola is spreading in the DRC of West Africa and the WHO has declared a public health emergency of international concern. Measle has also established a firm foothold. New cases of polio are turning up in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 1918 longshoremen working at the port of Philadelphia resupplying ships returning from the theatre of war, without personal contact or direct line of sight vision to anyone on the ships, contracted the flu and 40% died. In 1970, one of the last cases of smallpox was treated at a Catholic Hospital in the Ruhr Valley in Germany by designated Nuns. A very few were designated as care givers and were not to have contact with any others in the Convent. Again, without personal contact or direct line of sight to the patient, others cloistered in other areas of the hospital, came down with smallpox, 17 new cases with a high mortality rate. Modern science has proved to be a benefit and a curse. We do have vaccines, but compliance is voluntary, and cultural and ethnic beliefs alter acceptance. Cities are more densely populated and transmission of disease more rapid than 100 years ago. And we are just not prepared for the potential numbers that may be affected by new or resurgent organisms.

As a community, we do have the precepts to formulate plans and develop processes ensuring the survivability of our society. We have the intellect to formulate ideas and understand the consequences. And we have the passion to see through to the end. By reviewing our existing strategies, conops, guidelines, protocols, and mechanisms we can better coordinate with each other. We can do better at training and exercising. And we can communicate with everyone what they can expect during a major catastrophic event.

Mitch Moriber, DO- Secretary, Disaster Section, ACEP