Leadership and Advancement in EM-CCM: Can We Change the Landscape

Featuring Marie-Carmelle Elie, MD, FACEP, FCCM.

Read Video Transcript

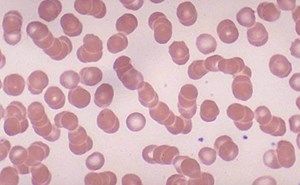

- [Marie-Carmelle] All right, so just to start off, I'll be sharing my personal journey in emergency medicine and critical care. But also describing some current metrics in diversity and equity and emergency medicine. I'll illustrate some examples of challenges and adversity that I've experienced in medicine. And describe some strategies for advancement from my perspective as an emergency medicine critical care physician. I'll also be leveraging some strategies that I've learned from this book that I read on The 48 Laws of Power and hoping that it might help all of us to think of strategies that we can use in our own professions. Some disclosures, I've no financial conflicts of interest. I neither endorse nor reject the opinions of the author from the book Power, Robert Greene. But I do believe that power is a construct. It's perceived by the very many people that are in our workplaces and in our environments. And it's important for us to understand how that plays a role in our environment as leaders. My pronouns are listed. I'm Black. Certainly not an expert in diversity and inclusion and health equity, but I'm hoping that my perspectives and experience as my own will resonate with some of you who are on the call. Now, some of the evidence regarding a lot- actually all the evidence regarding gender in my slides are binary. So may have limited relevance to members of the LGBTQ community. So I'm born and raised, I was born and raised in New York City. Never thought I'd leave. And I pretty much thought of the world this way, until I left New York. And many of you may be asking why in the world would I be in Birmingham, Alabama? Yes, there is a lot of football here, no shortage at all. But it's actually an incredibly beautiful campus. It has thousands of thousands of students and faculty with schools of nursing, medicine, dentistry. And it's actually an incredibly collaborative environment. And contrary to the city that I came from in Gainesville, Florida, before getting here, it's actually quite cosmopolitan and I've enjoyed all the restaurants out here since I've been here. But again, really beautiful place to live. And so, there's my plug for Birmingham for those of you that might wanna consider coming down here just to visit or to deliver a lecture in our space. So what's the state of diversity in academia? So gender, we know that the vast majority of physicians in medicine still are male compared to female. And when we look at the emergency medicine specialty in particular, women still represent the minority. Although there is a larger proportion that's represented in emergency medicine. Now when we look at the differences in salary in US public medical schools, there is quite a difference. This study demonstrated that there was approximately $20,000 difference across all specialties, with a preference towards paying men more money than women. And what's interesting is that over time, there has not only been a persistent gap that exists between men and women salaries. The gap has actually widened over time, suggesting that we really haven't made any progress in terms of ensuring that we can bridge that gap that exists between men and women in academic medical centers. When we look specifically at emergency medicine, those gaps exist here specifically. So this is data that comes from the AAAEM and it's about 24,000. So pretty comparable to the gaps that we see across all the other specialties. When we look at representation of women across medicine and along the leadership trajectory, you'll see that while in medical school, the majority of students that are graduating are female. You'll see that there is an attrition over time across the trajectory of medicine, leadership and medicine into those senior roles. And so, there is not only a gender gap that exists at the graduate level, but it continues to widen as we get to more senior leadership levels as well. When we look at faculty specifically, this study that was published in Academic Emergency Medicine was very interesting because what it did is it actually controlled for a number of factors that might be considered to be the reason why there might be a gap between the faculty rank in males and females. And so they controlled for things like age, years in residency, publications, grants, clinical trials. They even looked at RVUs. And after controlling for all of those things, males still had a much higher likelihood of being promoted to a higher rank compared to females in academic emergency departments. So how does looking at race fair in medicine? As you can see here, the vast majority of physicians in medicine are of the White race. And when we think about race and promotion, when we talked about this a little earlier, AAMC data demonstrates that while 26% of women are full professors and 19% of medical school department chairs are women, when you look specifically at the African American and Latino populations, they represent 4.6 and 6.9% of department chairs. I'm sorry, 4.6% of full professors and 6.9% of department chairs. A pretty substantial minority compared to their represented groups across medicine. In emergency medicine, the majority is White. But when you look at promotion, you'll see that while there's a pretty equal distribution of all of the races of the instructor and even at the assistant professor level, you start seeing the gaps when you move up to the associate professor and the professor level. So, one of the reasons why we suspect perhaps that, especially with gender that, you know, there is a gap and perhaps not as much of a representation of women in positions of leadership is that we worry that people leave. And we do know that this is happening. And in fact, AAAEM looked at this very specifically about three years ago. And what they found was compared to males and females, while males and females may very well leave for the same reasons, when specifically looking at females, there is a tendency to leave because of family, family balance. There is certainly some folks that are leaving for involuntary reasons are dissatisfied, but that's weighted heavily with the women as opposed to, oh, sorry, with the females compared to the males. So, this study was actually published, looking at a group of underrepresented minorities and women. And it was a qualitative survey and then interview that was performed amongst this group of faculty members from one academic medical center in the Southeast. And what they found were several themes around barriers to promotion and advancement in women, as well as in African-American and Latino faculty. Amongst women, what they found was women felt that their advancement was getting better over time. They were choosing family over advancement. Working mothers had difficulty meeting the demands of advancement. Bias impacted their advancement. Underrepresented minorities felt that advancement was also getting better. But they felt that because of their, because of lack of a pipeline, there were issues with them to get advancement. They also felt that there was bias and it was much harder to advance. The institutional climate however, it was, was pretty interesting. Because while those themes existed, the institution's perception was there was equal opportunity to advance. They felt that all of their groups were being treated with respect, but they also noticed that there was some racial tension within their organization. So, you have these sort of antithetical themes that present themselves between these groups, right? So the women and the faculty feel that there's bias and that there's barriers, but the institution themselves feel that, the institution perceives that those barriers don't quite exist and equal opportunity is present for advancement. So, what can we propose as a toolkit to help us to navigate this space? The toolkit that I'm going to present actually starts with the individual. And so, I mean, all individuals. All individuals that are a part of the community of academicians. And so, what I always tell people to do is to think about who they are and how they are represented or seen or present themselves in the academic environment. So what do you value? What's your personality? What are your threats, your triggers? What brings you a sense of respect and entitlement in your space? Then explore your bias. Because unless each of us are willing to explore our biases, then it's really hard for us to address biases that might exist in our environment, or that might be preventing us from being able to advance in our own space. There are also other things that we may wanna consider, especially amongst women. This is very well documented, that when they are in the clinical space they're treated differently compared to men. So thinking about what types of preparation rituals that you can sort of adopt in the clinical space that allows you to command the space, take care of your patients, is really important. And so this is a great article that walks through a perhaps a ritual that people can take on, or women specifically can take on to ensure that they get the respect, attention, that they require in order for them to take care of their patients. So in this example, what they state is that you should reaffirm sources of legitimate power, wear your white coat in the space, assume a code persona, adopt a powerful code stance. So, shoulders back, stand straight up, even pull out a stool and stand up a little higher than everyone else to give yourself a little bit more height, pull back your hair. And then give yourself permission, and I really like this, give yourself permission to suspend social norms. So, the reality is and I love this, that, you know, I've heard this before, that women will often get labeled as being bitchy witchy. And so, sometimes we are afraid of raising our voice or saying what we need to say in a commanding tone, because we don't wanna be labeled. But it may be appropriate if we're trying to take care of a patient. And so you might wanna suspend the social norms that you recognize might get you labeled and do what you need to do in the moment. But remember to go back and apologize afterwards. And take some accountability and say, I raised my voice. I used a very sharp tone, but please understand I did that for the patient care. I apologize if anyone may have been offended by the tone that I was using. But by no means was that meant to offend anyone here. There is stereotype threat amongst everyone, and it's not just those that are women and those from underrepresented groups that experience stereotype threat. But it's really important to acknowledge that it exists and identify ways of navigating it. So naming it, acknowledging it, admitting imperfection, but also, you know, patting yourself on the back and taking note of your achievements and focusing on your strengths are really great ways to navigate the stereotype threat and create a persona of confidence. So that takes time and practice. And so you gotta keep learning how to do that. Other things you might wanna consider is thinking about mentorship. And who's mentoring you and getting you to get beyond your stereotype threat and your imposter syndrome. I myself know that I've been in positions where perhaps I was offered a position or an opportunity for advancement. And I would always tell this person that I wasn't quite ready. I didn't think that I had done what I needed to do up to that point in order to take on this role. And having a mentor that had been with me for a very long time was great because he was able to encourage me to go ahead and pursue the thing that perhaps I wouldn't have pursued had he not helped me to identify that I personally had a stereotype threat. The other thing is, is that I put down on the bottom of the slide privilege is power. And oftentimes, especially as people of color, women, we don't necessarily feel like we have the privilege to ask for things or the privilege to step into the role, or the privilege of advancement. And changing again, our perception of where that privilege comes from and the idea that we deserve to be able to move up into these positions of an advancement is something that again, takes practice. And it's something that perhaps if we remind ourselves of, that we all have the privilege and we all are entitled to advancement and to be recognized, helps us to perhaps move past this space where perhaps we are our own worst enemies and not wanting to advance because we don't believe that we're ready, or don't believe that we're worthy. So specifically for faculty and leaders, you may be asking, well, we're talking about diversity, we're talking about leadership. Maybe I'm from a group that doesn't represent women or underrepresented minorities. What's in it for me? The reality is what's in it for you is a diversity bonus. What we know about diversity is that teams that are diverse actually perform homogeneous groups. So these bonuses include improved complex problem solving, innovation and more accurate predictions. And it's not only that, but if you wanna convert this into, or at least translate this into our clinical space, there are studies that suggest that creating diverse environments or in this particular case, having women take care of patients, we can see that they're actual mortality benefits when women are in the clinical space. In this particular study, where they looked at elderly patients that were hospitalized and specifically looked at the patients that were cared for by female versus male internists, there was a lower mortality and fewer readmissions compared to those that were taken care of by male internists. And they simulated the, they took the entire population of patients that were seen, and they calculated that there would've been about 32,000 fewer deaths had they all been taken care of by women versus men. Now mind you, we can never know that that's the case, but that's a pretty astounding figure when thinking about the impact that women have on the care space. There are other studies have also demonstrated that when women have been in a position to take care of a patient of another woman that that was having chest pain, that that woman was more likely to survive their care compared to if that same woman that was presenting with acute coronary syndrome MI was taken care of by a man. And as it turns out, while we're talking about the clinical space, a lot of the financial corporations have already figured this out. So this is a study that was performed by the McKinsey company. And there's actually several other reports just like this. But when they look at diversity by gender, or diversity by gender and ethnicity, they actually have a higher performance, financial performance in those corporations because of added diversity for gender and ethnicity. And there again, several other studies that look at this and what they all find is that by ensuring that there is diversity in their companies, it actually increases their ability to excel financially. So other strategies for faculty and leaders to think about is allyship. And so what is this? So allyship is when a colleague or a peer affirms, acknowledges, or celebrates and amplifies the achievements of the individual. And they do this openly and publicly in front of other people so that essentially the person's achievements are amplified in a way that everyone can see. Other ways that faculty and leaders can think about increasing diversity, but also setting our teams up for advancement, thinking about mentorship and coaching. Mentorship takes time, and it takes commitment. But it also takes an alignment of the goals of the mentee. And so I don't think that anyone should take for granted that mentorship does, it does take effort. And if you're not prepared to do this, you might, you know, definitely make sure that you're getting some, coaching yourself in the space to make sure that you're doing this the right way. But this is a great book, Athena Rising, written by Dr. Johnson. And in this book, he really describes how and why men should specifically mentor woman. And I learned a lot from this book. Men are, in this book he describes how men are really reluctant to mentor women. A lot of this has to do with the fact that they don't feel that they have the coaching. And a lot of them are just worried and anxious around the #MeToo movement. When in fact, this anxiety is definitely not valid for most men that do choose to mentor women. And men, most often are praised for this work. And rewarded when they do mentor women. What's notable also is specifically women of color, 59% of them have never had an informal interaction with a senior leader. And so, just pointing out that there there's an opportunity there for men to step up and do more mentorship, or provide more mentorship and allyship for women. And specifically women of color are isolated, and perhaps don't have as many opportunities. Coaching, coaching is not mentorship per se. Coaching is probably what we would describe that happens at the bedside every time we're with one of our residents, guiding them through a procedure, helping them to work through a pathway, a clinical pathway with a patient. And coaching is actually more advanced than mentorship in many ways, for those that are interested in leadership, and can be used to really focus on a particular area in which you are struggling, or perhaps identify a barrier or challenge. I personally have taken on coaching and have found it to be extremely, extremely helpful in my advancement in leadership. The other thing we wanna make sure that we're doing is that we're educating ourselves as best as we can. So we're picking up those books on mentorship and we're learning as much as we can about underrepresented minorities, about women, and not necessarily relying on them to tell us what they need. There's plenty of toolkits that are out there through the AAMC that can also assist in the space. We definitely wanna think about being anti-sexist, anti-racist in educating ourselves, but also being humble about the spaces that we don't understand. Making sure that we don't have policies that discriminate or bias. And look at ourselves, as well as our departments very carefully. In our department, as a chair, I had to do a pretty extensive salary assessment and analysis and identify ultimately that we did have a problem with gender bias in our department. And our salaries were, there was clearly a salary gap in our department, and I'm working on ensuring that we can eliminate the policies that exist that were not necessarily designed to be gender biased, but ultimately that was the outcome in our department. We wanna be able to create pipelines as well. So this is the study that was published between, amongst faculty that were at Emory and at Morehouse. And what they defined is that when they identified students in the undergraduate years, they were able to usher them through their graduate years in residency and encourage more admission of students, of underrepresented backgrounds into emergency medicine. And so, again, a really good example of how pipelines can actually help to produce more leaders and more physicians of a diverse background. There are other pipeline programs that have worked out like this, but other things that have worked really well, Indiana University actually has a program where they take on a junior faculty and they place them into professional development sessions twice a year. So not much time and not much of an investment from the institution, but twice a year. And what they found is after three years, that many of those faculty members that traditionally would not have advanced actually were in positions where they could advance in academic appointment. And I believe in that same study that was performed at Indiana University, there were at least two or three of them that went on to attain tenure. So, creating programs that specifically target and provide professional development and mentorship to members of the underrepresented minority groups and women have been shown to improve advancement. So the other thing you wanna think about doing is engaging your stakeholders. It's really hard to do a lot of the work that we're talking about without resources. And so engaging your stakeholders on everything you do is going to be important as you think about advancing those who are traditionally not advanced in your organization. And then, we can't do this work without engaging the women and the members of the underrepresented groups, who quite frankly are seeking these opportunities for advancement. So invite them for discussion. Respect, and value and protect their time. And I say protect their time once again, because oftentimes these groups are taxed to do a lot of the work around building these initiatives on their own, but don't necessarily get the time protected to do that kind of work. We also wanna seek feedback from them, but communicate the strategy when the strategy is present so that they know what to do. And then if there are some wins, or even if there aren't any wins, it's important to communicate those outcomes as well. And then finally investment. It's really important to think about investing resources, whether that's money or time, protecting people's time, encouraging independent funding and investing in allowing folks to travel and go to career development workshops, creating development workshops at your own institution, defining a mentoring or coaching program within your institution in order to align these individuals with a person that can help them to achieve their goals. And then finally, if there is truly a gap in salary, to invest in leveling that wage gap. So, why did I choose emergency critical care? When I was a PGY3 I was working with a gentleman that, actually with one of my favorite attendings, and there was a gentleman that had come in who was hypoxic and who we intubated. And this was an x-ray that looked just like his, and those were his post-intubation vitals. I was ready to put in a central line, get some more labs, start him on suppressors. I mean, this was like the perfect patient for me to resuscitate in the emergency department. And unfortunately, my attending looked at me and said, Carmelle, we can't do this. The patient has to leave right now. They have to go up to the ICU. Well, it turns out the ICU that I had already rotated through six months ago as a PGY2, had a PGY2 up there who was less- who basically didn't have the expertise to take care of this patient. And for whatever reason, my attending felt it was better at two o'clock in the morning to send this patient up there than to manage the patient in the emergency department. So as a PGY3, I encountered the notion that my attending was afraid of taking care of this patient in the ED. He didn't feel comfortable. Now mind you, I'm dating myself. So this was a long time ago. But there was a time in the emergency department where patients, the patient's illness perhaps exceeded what we felt we can do in the emergency department. And I thought it was important to learn what the next step was, and how to pursue taking care of that patient, if that bed wasn't available. Or if that patient had to wait an extra hour in our department. And as it turns out, you know, I think that's far more common now than it had been 20 years ago. So, I wanted to pursue critical care. And then this article came out and I thought, hold on. So someone is actually endeavoring to perform critical care in the emergency department. Well, I wanna do this. And so this article had come out only months after I had had this epiphany about the fear of taking care of sick patients in the emergency department. And I knew after reading this article, that that's exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to start critical care in the ED. The problem was is that my dilemma was that there were few graduates in the country. There was no peer group for consultation. There was no EM specific resource. There was no defined career path. There were like two fellowships. And so I was trying to do all this data gathering. And so I spoke to a lot of my peers. I spoke to junior faculty, senior faculty, and some said there was nothing to gain by doing this. I mean, there's nothing that you can do as a critical care physician that you couldn't do as emergency medicine. Others were really excited about the idea. But you know, most people just said, well, you're not gonna get a job. Ultimately, I made a cold call. I called the chief of trauma at Shock Trauma, Dr. Scalea, and I left a message with his secretary. And three days later, he called me at five o'clock in the morning. Actually, I'm pretty sure he did this on purpose. Woke me up and he said, hi, this is Dr. Scalea, how can I help you? And I woke up right away. And I said, well, sir, I'm interested in applying for your fellowship. So he talked to me about it and said, all right, well, I have a spot that just opened. If you're really interested, come on down. And I interviewed, and I got accepted into the program. Definitely one of the most intense years that I did. And then finally it was time for me to look for a job. And this is what didn't exist back then. There was no help wanted sign. There was no one looking for an EM-CCM graduate. And so I had to hustle. And in hustling, I traveled pretty much up and down the Eastern Corridor and couldn't really find anyone that was really in- I mean, people were intrigued, but not really interested. So, what did I have to do? So this is Law number 13, out of The 48 Laws of Power. When asking, appeal to their interest. So this is really all about negotiation. I really had to figure out, as a unicorn, what I was going to do to find a job. And what I identified was there were a lot of institutions that didn't necessarily have a sepsis program. And in the institution that I was applying, a lot of the sepsis patients were actually not surviving the hospital. In fact, I think at the time I'd started, the mortality from septic shock was 65%. It was something absurd. And I wanted an office, I wanted time in the ICU. I wanted ultrasounds, you know, I wanted stuff. And how was I gonna get all of this stuff? Well, I proposed that if they gave me ICU time and an office and bought a couple of ultrasounds, that I would build them a sepsis program and I would help with their mortalities. And they said, hmm, okay. Bet, you can join our department and we'll see how this goes. So I was able to get those things by negotiating. However, within a month of my arriving, and mind you at the time, this was the surgical department division of surgery, the emergency department, where they were going to give me time in a surgical ICU. Within a month of being there I encountered a person who didn't quite, was not quite pleased with my management in the emergency department. So Law number 19, The 48 Laws of Power, Robert Greene, know who you're dealing with, do not offend the wrong person. So apparently, after coming from a trauma institution, I really, I was very good at managing trauma patients. And so it turns out that I got a diagnosis that the chief of trauma didn't get at the bedside. And so this created a little bit of conflict. And I didn't recognize that this was gonna create a threat for me. And within two weeks I found that I was not going to be allowed to work in the surgical ICU. And so, conflict is not foreign to us in emergency medicine, but when you're an outsider, you have to recognize that you're an immediate threat. And you may not know who's threatened, but you've gotta know that it may exist out there. And you gotta sort of figure out where it is and sort it out and make sure that you're not threatening someone inadvertently, because I certainly did do that. So next Law, do not build fortresses to protect yourself, avoid isolation. So I went back to my surgical chair and said, you know, this is really important to me. I wanna work in the ICU. And we talked about the consideration of me working in the medical ICU. And he says, well, I can't promise you that you can go up there, but you can go up there and if they agree, then I'll allow it. So I go up to the medical ICU and I meet the chief and he's intrigued. I brought out my negotiation skills and I said, look, if you let me come up here, I'll continue working on sepsis. And I can teach your fellows advanced airway procedures and ultrasound and palliative care. And they said, all right, well, that sounds intriguing. And they let me start working in the MICU. By the end of my first year, I was the highest RVU generator in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. And they offered me a full time job in the MICU. My chair, my surgical chair renewed my contract instead. So Law 23, concentrate your forces. So, as it turns out, I left that institution and went to another institution and actually encountered the exact same threats when I arrived there, that I had in the previous institution. Essentially, I'm this outside entity. And so, rather than engage them initially, I basically created an alliance with these individuals, performed research with them, helped them with teaching. I taught them lots of lectures, but I didn't work in their ICU. And so over time, what I did is I established lots of stakeholders in the institution. With internal medicine, by building a sepsis program, with intensive care, by streamlining all the protocols, with administration, by designing algorithms and reducing the mortality and the length of stay for our sepsis patients, and with graduate medical education, by helping to develop palliative care in the ICU. So in transitioning to this institution and learning how to deploy this strategy, soon enough, I was often named, or people knew my people knew my name in the C-suite. And they knew that if my name was being mentioned, that they could say it with confidence and that I would deliver results. Ultimately over time, it became my brand. And so, Law number five, so much depends on your reputation, guard it with your life. So I'll stop there because I know that we're gonna be short on time. But I do think that it's important to think about strategically about leadership and where it leads you. I think that there, we know that there are lots of challenges and adversity that exists in leadership and in medicine, but it is important to think, not only strategically, but in thinking strategically, also making sure that you're aligning yourself with a mentor, thinking about coaching in order to navigate challenges, identifying those stakeholders to, again, fortify your forces and concentrate your forces and protect yourself. And with time, you'll find that those opportunities arise, and maybe any one of you can become a chair. So I'll stop there and answer any questions that folks may have.

[Moderator] Thanks, Dr. Elie. I think what you're not quite hearing is the roaring applause that you would likely hear if we were all in a room together, but there are people clapping in the background there. That was just incredibly inspiring. You covered a ton of ground in your stories, just awesome. Maybe we'll just take two minutes for some questions now, and then we'll head off into our breakout room. And questions can come either by unmuting and just asking the old fashioned way, or I guess not quite the old fashioned way, or putting them in the chat.

[Woman] Have there been any programs as chair that you have kind of spearheaded or inherited and further developed to retain female faculty members because of that rate of attrition and lack of progression?

[Marie-Carmelle] Yeah, absolutely. So in arriving, I've only been here for about a year and we had 15, I'm sorry, 20% females, right? So we actually have a lower population of women in our department than we do in the discipline of emergency medicine. So the answer to your question is absolutely yes. I think we have to be intentional about this. I talk about it to our department and I ensure that they understand that this is not a capricious ask. So that book that I mentioned, Athena Rising, I'm purchasing it for all of the men so that they have the opportunity to mentor female residents, female medical students, female junior faculty, and they won't be afraid of doing it. But what we're also doing is we're also focusing on some of the needs of the women faculty here. So, when I talked about people's authentic self and knowing how to sort of find your own, acknowledge your own privilege, that's hard for a lot of people, but especially for women, when oftentimes they feel as if, you know, they often feel very lucky to be in a position that they're in. They will not negotiate. And they'll wait to be asked, rather than pursue opportunities. So, we actually have some programs on campus that are designed to help women to transition from junior to mid-career faculty. But we're actually going to be establishing a biannual retreat here in the department where we have facilitators that specifically work with women and help them work and coach through some of the issues that they are encountering in our environment. Now, there are very few women in my department, so I have an opportunity to do that right now. Hopefully in recruiting more women to the department, I'll have an opportunity to make it, to do this on a much broader scale down the road.

[Woman] Thank you.

[Woman] Dr. Elie, can you think or talk about some of the specific training or programs that you've participated in? I think a lot of us have enthusiasm and opportunity, but there is a certain skill set that is important and effective in implementing things. Is there anything that you've done that you would recommend?

[Marie-Carmelle] So a few, not very specific to this space, but I'll tell you that I've done a lot of training in communication, around difficult conversations with patients. And it turns out that that is very translatable into our space as providers, that often deal with microaggressions and knowing how to navigate through a discussion with a peer that perhaps says something that might be offensive. But also in dealing with anger or other perhaps overt reactions that may make it difficult as any provider to work in the environments that we work in. So I've learned how to use silence a lot. I've also learned how to deflect, and I've also learned a lot about allyship when I'm really just amplifying the words and the accomplishments of the other people that are in the room that often get discounted. So, that's one. But specific courses, the AAMC actually has a great course for junior and mid-career women. So I would say that was, if you can get into that course through your institution, I would highly recommend it. I'm applying for ELAM. I've heard of a lot of women that are in positions of leadership within their organization that have gone through that program that have done very, very well. And have found that has been very uplifting for them and has helped them on their career trajectory. So I'm applying and I plan on going to that program. But I'll have to be honest, I was really lucky that I was able to have my own funding in my department for professional development and coaching. So I had a coach who I met once a month, and that coach helped me to navigate through specific challenges. Specifically, I think there was a point where I got to, I didn't know how to interpret what was happening in my organization and why I wasn't moving along the career trajectory or perhaps the advancement trajectory that I would've liked. And that coach helped to coach me through some of the relationships I had within the organization, but also helped coach me through which opportunities I should take on, and which ones I should probably set to the side. And I can tell you that it really was beneficial to have coaching during that time. And again, and it also helped me to identify perhaps what some of my own personal barriers were and my stereotype threat, and my imposter syndrome that I had. So other than the AAMC program, I think coaching is highly, highly, highly, highly valuable and mentorship.