It’s Not Just the Sniffles: Approach to Diagnosis and Management of Sinusitis in the Pediatric Population

Introduction and Background

Emergency medicine physicians pride themselves on differentiating “sick” versus “not sick” with a rapid assessment. In children, the “sick” can be a profound, albeit horrifying, sight, like an infant that is limp in its mother’s arms or a toddler tripoding and gasping for air with stridor that can be heard from across the department. While these patients become progressively easier to recognize throughout one’s practice, it is harder to identify certain threats simmering just below the surface.

One such example is bacterial sinusitis, an illness that frequently presents as a common cold. It can have the same persistent runny nose and/or cough. In fact, it typically appears as the other 6-8 viral upper respiratory infections (URIs) that young children experience annually.1 While typical viral rhinosinusitis is usually harmless, acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) has the potential to wreak havoc. If left untreated, the complications of ABS can range from local development of preseptal cellulitis all the way to intracranial abscesses.2 In this review, we will discuss the hallmarks of viral rhinosinusitis and ABS, its most significant complications, as well as current guidelines and practical indications regarding initiation of antibiotic treatment.

Anatomy and Development

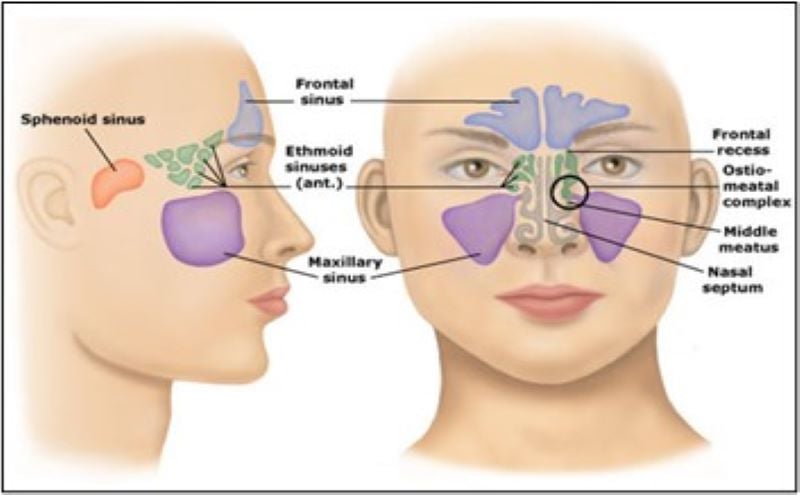

In the adult patient, there are several paranasal sinuses present and worth mentioning: the ethmoid, maxillary, sphenoid, and frontal sinuses3 (Figure). Within a healthy sinus, mucous is produced from mucous glands, which is then mobilized and cleared through the ostia (openings) by constantly beating cilia. The sinuses are largely interconnected through a common point of drainage that is known as the ostiomeatal complex (OMC).4 As we will later discuss, disruption of this system can lead to the accumulation of infectious organisms within the sinuses and subsequent development of sinusitis.

Interestingly, we are not born with this complete sinus system fully developed. In fact, the ethmoid sinuses are the largest of all at birth, while the sphenoid and maxillary sinuses start to develop significantly in early childhood, and frontal sinuses only reach full maturity in early adolescence.5-7 As such, the timing of sinus development determines which sinuses are more frequently infected in different age groups, as well as the potential complications of ABS due to the location of infection.

Definitions, Pathophysiology and Etiology

As the suffix implies, sinusitis refers to the inflammation of the paranasal sinuses. This acute inflammatory process can be secondary to an allergic or infectious process, with the latter including both viral and bacterial etiologies. Most sinusitis is caused by viral infections, with the most common organisms being rhinovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, and adenovirus.7,8 When a bacterial source is identified, the most common organisms involved are akin to those implicated in acute otitis media (AOM), including Streptococcus pneumoniae, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.9 In complicated bacterial sinusitis, infections are typically polymicrobial, although Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are frequently present.10

There are several different factors that may predispose one to the development of sinusitis through the disruption of the normal mucociliary clearance system. These include inflammatory and obstructive processes that prevent normal passage of mucous (ie, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, foreign bodies, tumors), as well those that impact the normal function of the cilia (ie, cystic fibrosis, second-hand smoke exposure). Allergic and viral inflammatory processes are the most significant risk factors for the development of ABS, which ultimately complicates 5-10% of pediatric viral URIs.2,7,9

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The presentation of acute sinusitis is often identical to those of viral upper respiratory infections in children. Some of the most common symptoms include cough, runny nose, congestion, headache, and fever. The first challenge is differentiating the infectious from non-infectious sinusitis, namely, allergic sinusitis. While overlap clearly exists, certain clues of an allergic source include seasonal occurrence, family/patient history of atopy, itchy/watery eyes, and identifiable allergens. On examination, patients will often have conjunctival injection, cobblestoning of the throat, and pale nasal mucosa.11 The next challenge is then differentiating acute bacterial sinusitis from more typical viral etiologies.

Classically, bacterial superinfection from a viral origin follows a biphasic clinical timeline, with more severe fever and symptoms occurring later in a patient’s clinical course. Additionally, when attempting to identify a bacterial source, one might think that purulent nasal discharge, fever and malodorous breath are key components. While this can be the case, ABS can present in a variety of ways with any quality of nasal discharge. Because of this, both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) have provided guidelines to encompass the breadth of presentations of ABS, as well as treatment recommendations. These guidelines were most recently updated/published in 2013 for the AAP, and 2012 for the IDSA. They have proposed that a diagnosis of ABS can be made when any of the following below criteria are met:

- Persistent respiratory symptoms (ie, nasal discharge of any quality and/or cough) for >10 days without improvement

- Biphasic course with worsening/new onset respiratory symptoms/fever following a typical viral URI

- Severe onset fever (>102.2°F/39°C) and purulent nasal discharge for at least 3 days

The aim of these criteria is to provide instances where ABS would be more likely than the usual viral rhinosinusitis. Uncomplicated viral URIs usually last around 5-7 days, with a severity peaking around day 3-6. Symptoms may continue for a longer stretch of time, even past the 10-day mark, but most importantly, are resolving. If a fever is present, it normally is present early in the course of illness, followed by predominance of respiratory symptoms.11,12

The AAP stresses that the diagnosis of ABS is a clinical one, and that imaging should not be routinely used. When plain radiographs, CT or MRI images have been obtained of the sinuses, there were “significant abnormalities” present in both patients with uncomplicated viral URIs as well as patients with ABS. These abnormalities include air fluid levels and generalized mucosal thickening. While imaging could certainly “rule out” sinusitis as a diagnosis, it cannot be reliably used to distinguish ABS from a viral URI. The only setting in which diagnostic imaging should be obtained is if there is concern for either intracranial or ocular complications of ABS.11

Complications

The complications of bacterial sinusitis are caused by local spread of infection to the nearby bone and orbit and can even extend intracranially. Bony involvement leads to osteomyelitis, with the most common sites being the maxillary and frontal bones, the latter sometimes referred to as “Pott’s puffy tumor.”2,11,13 The orbital and intracranial complications are further outlined in the table below.

Table: Orbital and intracranial complications of bacterial sinusitis

| Orbital | Intracranial |

| Periorbital cellulitis | Epidural abscess |

| Subperiosteal abscess | Subdural empyema or abscess |

| Orbital cellulitis | Cerebral abscess |

| Optic neuritis | Meningitis |

| Cavernous sinus thrombosis | Sagittal sinus thrombosis |

Orbital involvement most commonly spreads from the ethmoid sinuses due to their close proximity and, therefore, are particularly prevalent in younger children less than 5 years old.14 Patients who develop periorbital/preseptal cellulitis will present with local swelling and erythema of the eyelid. If the infection spreads further progressing to orbital/postseptal cellulitis or abscess formation, patients may present with proptosis, limited and/or painful extraocular motion, blurry/double vision, and even pupillary defects. Cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) can present with additional features, including cranial nerve III, IV, V and VI palsies (extraocular motion deficits, dilated pupil) or sympathetic chain compression (Horner syndrome). With the exception of periorbital cellulitis, orbital complications are particularly morbid and can lead to blindness.15

Intracranial complications are primarily caused by infection of the frontal sinuses and are therefore more likely to occur in older children.14 As many of the intracranial complications involve the formation of abscesses and even meningitis, patients will typically present more clinically ill, and have higher associated morbidity and mortality.15 Symptoms can include fever, severe headache, focal neurologic deficits, altered mental status, lethargy, nausea/vomiting and seizures. In some cases, patients have even been found to have acute infarctions on MRI because of these infections.14

Treatment and Follow Up

For allergic and viral sinusitis, there are no specific treatments that are universally recommended. Many providers advocate for the use of intranasal steroids, nasal irrigation, mucolytics, antihistamines, and decongestants for symptom management.15 Regarding these adjunctive therapies, there is limited data supporting their use or demonstrating outcome-driven benefit.11,12

For bacterial sinusitis, antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of treatment, with recommendations subdivided based on uncomplicated versus complicated ABS. For uncomplicated ABS, oral antibiotics should cover S. pneumoniae, non-typeable H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. Given this, it is recommended to start with either high-dose Amoxicillin or Augmentin. The IDSA recommends the use of Augmentin given the increasing beta-lactamase resistance in S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae species.11,12,16 For penicillin allergy or prior antibiotic failure, third generation cephalosporins including Cefdinir, Cefuroxime, and Cefpodoxime can be used.11 Dosing recommendations are listed below:

- Amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day divided doses twice daily

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) 90 mg/kg/day Amoxicillin divided doses twice daily

- Cefdinir 14 mg/kg/day either once daily or divided doses twice daily

- Cefuroxime 30 mg/kd/day divided doses twice daily

- Cefpodoxime 10 mg/kg/day divided doses twice daily

If the patient has significant nausea and vomiting and/or cannot tolerate oral antibiotics, a dose of either IV or IM 50 mg/kg Ceftriaxone can be given. Assuming the patient has improvement, oral antibiotic therapy can be initiated 24 hours following Ceftriaxone administration. The total antibiotic course is recommended for a minimum of 10 days or continued for 7 days past symptom resolution.11,12,16

Follow-up is of key importance in ABS and should occur within 72 hours following initial evaluation and initiation of therapy. If the patient fails to improve or has worsening of symptoms, the antibiotic should be changed (for example, transitioning from high dose Amoxicillin to Augmentin or a Cephalosporin). If symptoms have significantly worsened, the development of complications should be considered, with imaging and/or admission for IV antibiotics strongly considered.11,12,16

Patients with complicated ABS include those with any of the orbital, bony, or intracranial complications previously mentioned, and require admission and initiation of IV antibiotics. As previously discussed, these infections are typically polymicrobial, although S. aureus and MRSA are often identified. Because of this, recommendations of parenteral antibiotic regimen include the use of Vancomycin with additional broad spectrum and anaerobic coverage, including either Piperacillin-Tazobactam (Zosyn), Ampicillin-Sulbactam (Unasyn) or Ceftriaxone (Rocephin) + Metronidazole (Flagyl).11,12,16 Dosing recommendations are listed below:

- Vancomycin 40-60 mg/kg/day with Q6 hour dosing PLUS any of the following:

- Piperacillin-Tazobactam 240-300 mg/kg/day of Piperacillin with 3-4 doses daily

- Ampicillin-Sulbactam 200-400 mg/kg/day with Q6 hour dosing

- Ceftriaxone 50-100 mg/kg/day either daily or divided doses twice daily PLUS Metronidazole 22.5-40 mg/kg/day with 3-4 doses daily

Concurrently with the initiation of antibiotics, consultation with certain specialists may be required to determine the need for surgical debridement, washout, or I&D. These include Otolaryngology (ENT), Ophthalmology, and Neurosurgery, depending on the site of infection.

While this review covers current recommendations regarding sinusitis and ABS management, there are a few key remarks. Patients diagnosed with ABS based on the first AAP clinical criterion (persistent symptoms for >10 days) can be managed with a “wait and see” prescription, or with no initial prescription for antibiotics. This assumes that the patient will have guaranteed follow-up within 72 hours for reassessment, with the option to hold antibiotics if clinically improving at that time. One other exception are patients diagnosed with periorbital/preseptal cellulitis. While this technically falls into the category of complicated ABS, it can often be managed with oral, outpatient antibiotics, and admission is often reserved for younger patients, more extensive cases, possible orbital involvement, or those with prior treatment failure.11,12,16

Take Home Points

- The majority of acute sinusitis is caused by allergic or viral etiologies

- Acute bacterial sinusitis complicates roughly 5-10% of viral URIs

- Diagnostic criteria for bacterial sinusitis include:

- Persistent respiratory symptoms (ie, nasal discharge of any quality and/or cough) for >10 days without improvement

- Biphasic course with worsening/new onset respiratory symptoms/fever following a typical viral URI

- Severe onset fever (>102.2°F/39°C) and purulent nasal discharge for at least 3 days

- Advanced imaging should only be performed when there is concern for development of orbital or intracranial complications. These include osteomyelitis, abscesses, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and meningitis

- Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for uncomplicated bacterial sinusitis with options including:

- High-dose Amoxicillin

- Augmentin

- Third generation Cephalosporins

- Patients require follow up within 72 hours for reassessment after initiation of antibiotics

- Most cases of complicated bacterial sinusitis will require admission with IV antibiotics and surgical consultation, with options including:

- Vancomycin + Piperacillin-Tazobactam

- Vancomycin + Ampicillin-Sulbactam

- Vancomycin + Ceftriaxone + Metronidazole

Figure: Reprinted with permission from UpToDate. www.uptodate.com

References

- Fendrick, A. M., et al. "Ekonomsko breme virusne okužbe dihalnih poti, povezane z gripo, v ZDA." Arch Intern Med 163.4 (2003): 487-494.

- Nash, David, and Ellen Wald. "Sinusitis." Pediatrics in review 22.4 (2001): 111-117.

- UpToDate 2022. “Paranasal Sinus anatomy” in Patient education: Acute sinusitis (sinus infection) (Beyond the Basics), Accessed from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image/print?imageKey=ONC%2F78790&topicKey=PC%2F83012&source=see_link on June 21, 2022.

- McLaughlin, Robert B., Ryan M. Rehl, and Donald C. Lanza. "Clinically relevant frontal sinus anatomy and physiology." Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America 34.1 (2001): 1-22.

- Jones, Landon, Cantor, Richard. “Know When the Paranasal Sinuses Develop in Kids”. From ACEPNow 40:2, https://www.acepnow.com/article/know-when-the-paranasal-sinuses-typically-develop-in-kids, Feb 19, 2021.

- Zalzal, Habib G., Daniel C. O’Brien, and George H. Zalzal. "Pediatric anatomy: Nose and sinus." Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 29.2 (2018): 44-50.

- Tan, Ricardo, and Sheldon Spector. "Pediatric sinusitis." Current allergy and asthma reports 7.6 (2007): 421-426.

- Brook, Itzhak. "Microbiology of sinusitis." Proceedings of the American thoracic society 8.1 (2011): 90-100.

- Marom, Tal, et al. "Acute bacterial sinusitis complicating viral upper respiratory tract infection in young children." The Pediatric infectious disease journal 33.8 (2014): 803.

- Mulvey, Carolyn L., et al. "The microbiology of complicated acute sinusitis among pediatric patients: a case series." Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 160.4 (2019): 712-719.

- Wald, Ellen R., et al. "Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years." Pediatrics 132.1 (2013): e262-e280.

- Chow, Anthony W., et al. "IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults." Clinical infectious diseases 54.8 (2012): e72-e112.

- Patel, Neha A., et al. "Systematic review and case report: intracranial complications of pediatric sinusitis." International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 86 (2016): 200-212.

- Wiersma, Alexandria J., and Tien Vu. "Intracranial complications of pediatric sinusitis." Pediatric Emergency Care 34.7 (2018): e124-e127.

- Carr, Tara F. "Complications of sinusitis." American journal of rhinology & allergy 30.4 (2016): 241-245.

- Fang, Andrea, Jasmin England, and Marianne Gausche-Hill. "Pediatric acute bacterial sinusitis: Diagnostic and treatment dilemmas." Pediatric Emergency Care 31.11 (2015): 789-794.

Alexis Luedke, MD and Jaryd Zummer, MD