How to Diagnose Appendicitis in a Child

Jennifer Purcell, DO, Ultrasound Fellow, Grand Strand Medical Center, Myrtle Beach, SC

Justin Hanson, DO, Emergency Medicine Resident, Grand Strand Medical Center, Myrtle Beach, SC

Casey Wilson, MD, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Grand Strand Medical Center, Myrtle Beach, SC

Case

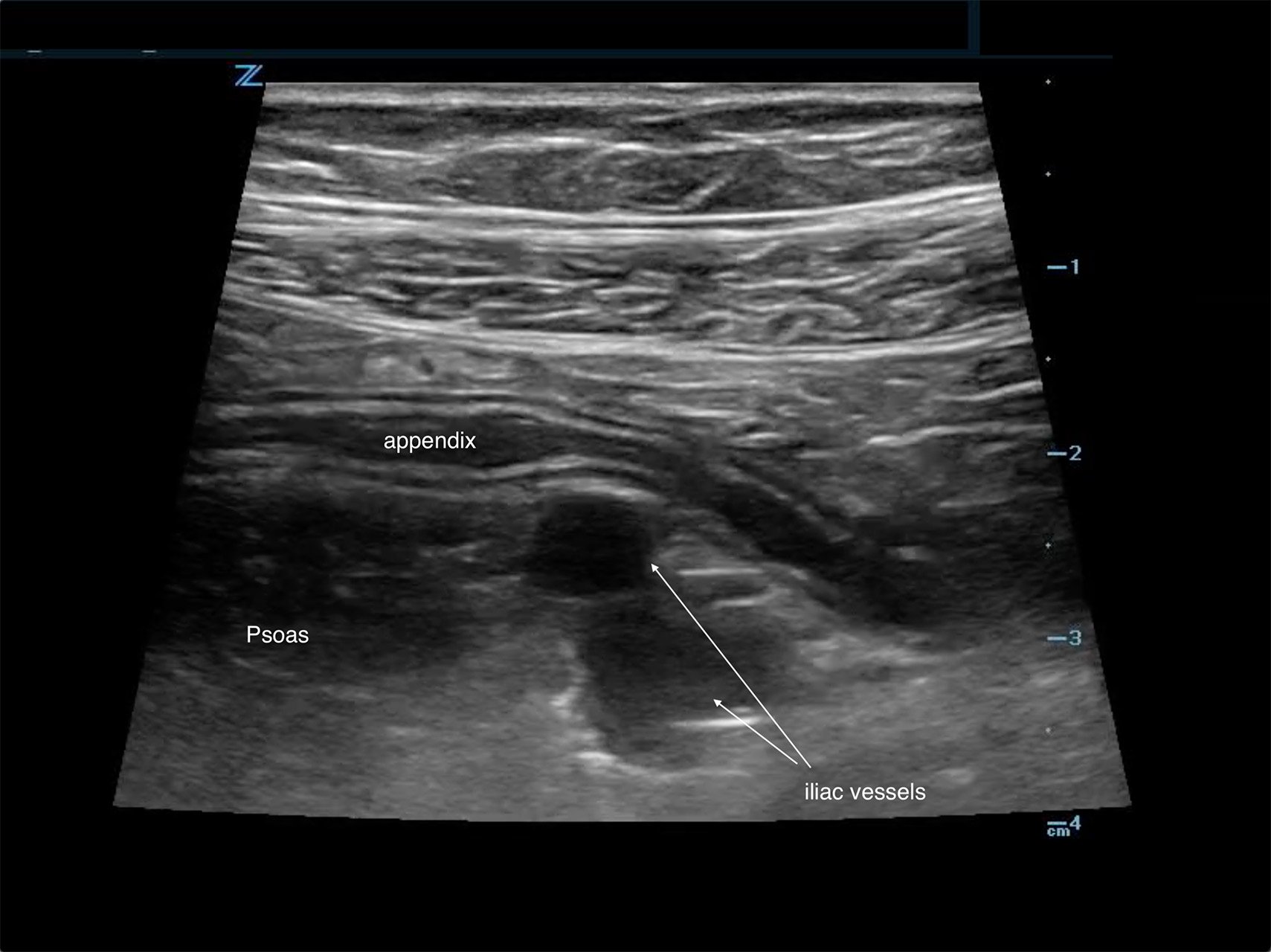

A 14-year-old female with a past medical history of anxiety and bipolar disorder presented to the emergency department with constant, sharp, non-radiating right lower quadrant abdominal pain. The pain began suddenly two nights ago and worsened with movement. She denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fevers, or chills. On physical exam, her abdomen was tender to palpation in RLQ and RUQ with rebound and guarding. Labs demonstrated a leukocytosis of 12.9k with no other remarkable abnormalities. Given the broad differential of appendicitis vs ovarian torsion vs gallbladder disease, bedside ultrasound was performed. A non-compressible dilated appendix 7.3mm in diameter with an appendicolith present. (Image 1) Comprehensive radiology ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated a non-peristalsing 6.5 x 1.1 x 1.6 cm tubular structure in the right lower quadrant concerning probable appendicitis. General surgery was consulted, and the patient underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy the same day. She underwent the procedure without complication and was discharged the following day.

Image 1. Image from case showing a dilated appendix suggestive of acute appendicitis with appendicolith and target sign present.

Introduction

Appendicitis often presents in the pediatric population to the emergency department, and is the most common pediatric surgical emergency, with a lifetime risk of 7%.1 But appendicitis pain can be difficult to differentiate clinically from other causes of abdominal pain, leading to misdiagnosis.2 Clinical scoring systems have been developed to help clinicians rule in and rule out appendicitis, but when used without adjunctive imaging they have lower sensitivity and specificity.2 Although CT is highly accurate in evaluating for appendicitis, it is estimated that the lifetime risk of developing cancer after one abdominal CT scan in a 1-year-old child is increased by 0.18%.3 Therefore, ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality in children to avoid the harmful effects of radiation.1 Recent trends in CT utilization in children show reduction over the last ten years, though this is largely driven by Pediatric EM physicians.4 The tools and skill set are available to decrease CT utilization for all emergency medicine providers. For clinicians working in rural and critical access settings, free-standing emergency departments, or facilities that lack access to 24/7 radiology ultrasound, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can rule in acute appendicitis for definitive management and may obviate the need for CT.5 Discovering acute appendicitis on bedside ultrasound can help to expedite surgical consultation or transfer in times when radiology ultrasound is not readily available.

Bedside ultrasound is highly specific for diagnosis of acute appendicitis and is increasingly used in pediatric and adult emergency departments for the pediatric patient presenting with abdominal pain.6 With ultrasound training becoming more prolific and machines more readily available, emergency physicians should be utilizing point-of-care ultrasound to attempt to diagnose pediatric appendicitis. One recent study reported pediatric emergency physicians had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 93% for diagnosing appendicitis with bedside ultrasound.7 With training and practice, we surmise that all emergency medicine physicians can add this advanced point-of-care ultrasound skill to their clinical toolkit in emergency care. In this article, we will discuss the key techniques and findings on ultrasound to diagnose appendicitis both efficiently and accurately, all while potentially reducing radiation exposure to pediatric patients.

Pediatric patient positioning

It is optimal to perform the exam while the pediatric patient is supine, (Image 2), with pain medication given and some sort of distraction. If bowel gas or a retrocecal appendix makes visualization difficult in this position, try placing the child in the left lateral decubitus or the left posterior oblique position, then scan through the right flank in a coronal plane, parallel to the long axis of the psoas muscle. (Image 3) This position has the added benefit of distracting the child by having them lie on their side and look at the ultrasound machine (or tablet) as you scan.

Image 2. Patient supine and starting in the RLQ

Image 3. Left lateral decubitus or the left posterior oblique position

Equipment and Procedure

Consider your patient and their unique developmental and age-appropriate needs before you begin your ultrasound exam; this informs the physical set-up of the room and who you need on hand to assist with your ultrasound exam. Having distraction techniques at your disposal such as a child life specialist, tablets, toys, or a sheet to hold up and block the child’s view may help to quell an anxious pediatric patient – flexibility is key. Depending on the child’s age, they may enjoy playing with the ultrasound gel or watching the images on the machine “like a video game.” Parents can sometimes be instrumental in distraction; otherwise, they may need to be excused to obtain optimal images in a short window of time. Some children enjoy holding the probe, “taking selfies,” and helping you to obtain images.

The high-frequency linear transducer (8-15 MHz) is ideal for pediatric patients due to their smaller body habitus. For larger children and teenagers, a low-frequency curvilinear transducer (2-5 MHz) might optimize image resolution to demonstrate the appendix at greater depths. Another example of a lower frequency transducer that is ideal for pediatric abdomens is the 8C microconvex probe (4-10 MHz). Use your identification of landmark anatomy (as described below) to increase or decrease your depth for better visualization of the appendix depending on the patient's size and where their appendix lies.

When imaging pediatric abdomens, we adopt the mantra “scan now, measure later.” You will want to focus on the greatest area of concern and save high yield clips that you can later evaluate in detail and provide measurements after exam completion. You may only be afforded several seconds of investigation with a minimally compliant child, so focus your effort on finding the relevant anatomy and saving clips rather than interpreting simultaneously.

Asking a verbal child where they are experiencing the most pain will likely allow you to begin your exam at a location where the appendix is irritating the peritoneum. (Image 4) The most common anatomic position is a retrocecal or pelvic appendix, so starting in the right lower quadrant is a safe bet.8 Once the point of maximal tenderness is identified, use graded compression to visualize the bowel and evaluate for pathology. “Graded compression” is a technique to gradually put more pressure on the probe to displace the underlying bowel gas to visualize the appendix and assess compressibility. If no appendix is identified at the point of maximal tenderness, move the probe to a transverse RLQ position with the indicator toward the patient’s right, and identify the anatomic landmarks: the iliac vessels and psoas muscle. The appendix is often located ventral or medial to these structures. If you are having trouble finding the relevant anatomy, sometimes beginning in the midline to identify the bladder, and sliding the probe to the patient’s right can help you identify your landmarks of the psoas muscle and iliac vessels more readily. Looking between the bladder and the iliac vessels is also advised to identify a deep pelvic appendix. If the child has a full bladder, it can augment visualization of surrounding structures by providing a better acoustic window.

Image 4. Appendicitis causing irritation peritoneum of the internal oblique and sartorius muscles

Color flow can help delineate the iliac artery and vein from bowel and musculature and should be utilized during the appendix ultrasound. An emphasis should be made to continue using graded compression, as consistent pressure can fully compress a normal appendix making it more difficult to locate. You should save clips and still images with and without compression in multiple planes and apply color flow over the appendix as well.

Appendicitis Identification

The appendix is most reliably found in the right lower quadrant; the base extends from the proximal cecum and lies anterior to the psoas muscle and the right iliac vessels. Most of the time the distal tip is retrocecal, though the challenge in localization is augmented as the appendix can be pelvically oriented (Images 5 and 6) or directed elsewhere in the abdomen. The normal appendix is tubular, non-peristalsing, compressible, and blind-ended, measuring less than 6 mm. (Image 7)

Image 5. Normal appendix

Image 6. Normal appendix (Yellow: Appendix, Red: Iliac Artery, Blue: Iliac Vein)

Image 7. Normal appendix, longitudinal view; appendix ending in blind pouch

When appendicitis is present, the appendix will measure greater than 6 mm from outer wall to outer wall, with a wall thickness greater than 3 mm and lack compressibility. (Images 1, 8, and 9) (Remember, you may want to do these measurements after you have obtained your images, given your patient a high five and a sticker, and stepped aside to perform measurements on the machine.) An inflamed appendix can demonstrate a “ring of fire” with enhanced color flow. Secondary findings you may see include: an appendicolith, (Image 1), periappendiceal free fluid (Image 10), a target sign (Image 1), enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, thickening and hyperechogenicity of the overlying peritoneum (Image 8), dilated and hypoactive small bowel, and thickening of the apical cecal pole.

Image 8. Dilated appendix with peri-appendiceal rupture

Image 9. Blind pouch, longitudinal view of acute appendicitis, measuring outer wall to outer wall

Image 10. POCUS showing a dilated, non-compressible appendix (*) with periappendiceal fluid (^)

Discussion

Although appendicitis could be considered a clinical diagnosis, few surgeons in today’s environment of medical litigation and highly accurate imaging will proceed to the OR without imaging confirmation. A recent publication promotes the use of ultrasound in pediatrics and using MRI or CT scan for non-diagnostic or equivocal cases.9 Ultrasound can be done quickly at the bedside and your pediatrics patients can receive an expedited diagnosis at your hands. One study demonstrated that patients with a non-visualized appendix on ultrasound and otherwise normal scans are at lower risk of appendicitis.10 Therefore, clinical observation should be considered before ordering a CT scan in this population. By becoming more comfortable with your pediatric appendix ultrasound you will be able to augment your clinical gestalt, narrow your differential quickly with a positive scan, have healthy conversations with consultants, and nail the diagnosis. If you can avoid even one abdominal CT scan in a small child, you should feel accomplished!

References

- Petroianu A. Diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Int J Surg. 2012; 10(3):115-9.

- Hao T, Chung N, Huy H, et al. Combining ultrasound with a pediatric appendicitis score to distinguish complicated from uncomplicated appendicitis in a pediatric population. Acta Informatica Medica. 2020; 28(2):114-8.

- Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, et al. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001; 176(2):289-96.

- Hryhorczuk AL, Mannix RC, Taylor GA. Pediatric abdominal pain: Use of imaging in the emergency department in the United States from 1999 to 2007. Radiology. 2012; 263(3):778-85.

- Khan U, Kitar M, Krichen I, et al. To determine validity of ultrasound in predicting acute appendicitis among children keeping histopathology as gold standard. Ann Med Surg. 2019; 38:22-7.

- Talley BE, Ginde AA, Raja AS, et al. Variable access to immediate bedside ultrasound in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011; 12(1):96-9.

- Tollefson B, Zummer J, Dixon P. Emergency physician-performed bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of acute appendicitis in a pediatric population. J Miss State Med. Assoc. 2017; 58(1):10-4.

- Zacharzewska-Gondek A, Szczurowska A, Guzinski M, et al. A pictoral essay of the most atypical variants of the vermiform appendix position in computed tomography with their possible clinical implications. Pol J Radiol. 2019; 84;e1-e8.

- Lawton B, Goldstein H, Davis T, et al. Diagnosis of appendicitis in the paediatric emergency department: An update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019; 31(3):312-6

- Stewart JK, Olcott EW, Jeffrey B. Sonography for appendicitis: nonvisualization of the appendix is an indication for active clinical observation rather than direct referral for computer tomography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2012; 40(8):455-61.