Tips and Tricks: Using Ultrasound to Ace Your Next Lumbar Puncture

Background

Lumbar puncture (LP) is a commonly-performed procedure in the Emergency Department (ED), with a failure rate as high as 50% (particularly in pediatric and obese patient populations).1-3 The use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for lumbar puncture has been gaining increasing support in the literature, as it has been shown to improve the ability to obtain cerebrospinal fluid,4-7 improve first-attempt success rates,6,7 reduce needle retractions and redirections,5 reduce traumatic LPs,5-7 and shorten the procedural duration.6 In this article we will discuss how to perform an ultrasound-assisted LP in the ED setting.

Image Acquisition

Ultrasound-assisted LP is typically performed as a static technique, using ultrasound to identify and evaluate the intervertebral spaces, marking the skin overlying the desired location, and then performing the LP at the marked site using conventional LP technique.4,5,7,8

The patient should be positioned for the procedure prior to image acquisition, to avoid movement of skin markings after imaging. Ultrasound can be used with patients in either the upright or lateral decubitus positions. In pediatric and non-obese adult patients, a high-frequency linear transducer is the probe of choice. In patients with several centimeters of tissue overlying the spinous processes, the curvilinear probe may be more optimal for identifying the relevant anatomy.

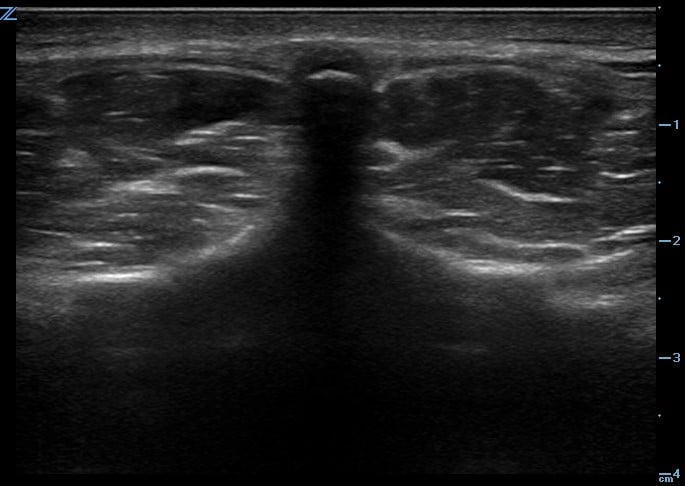

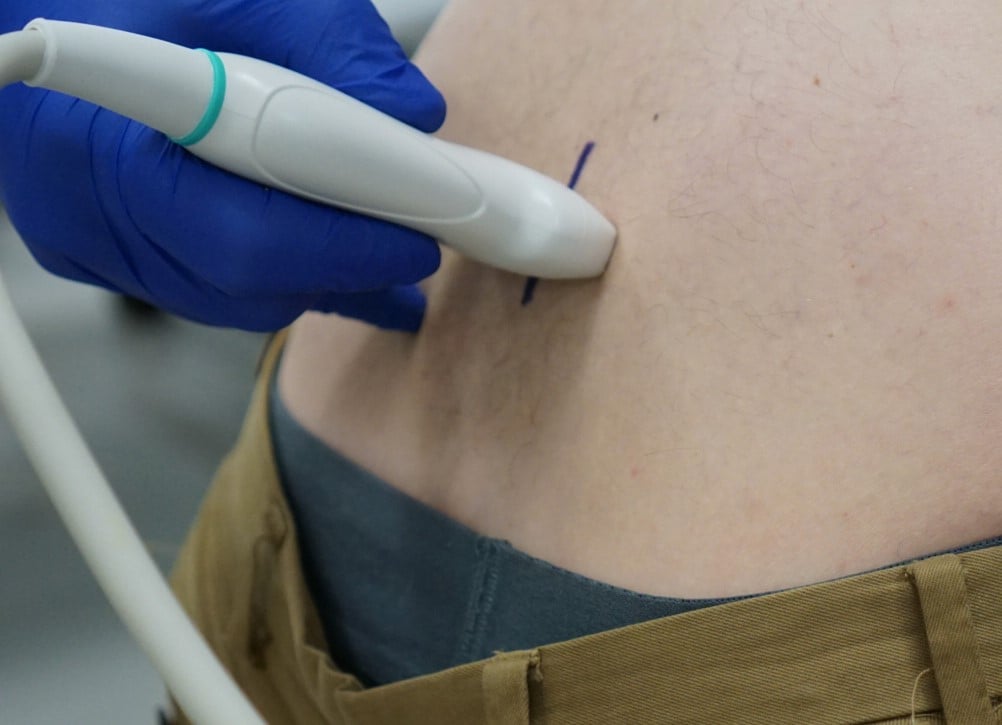

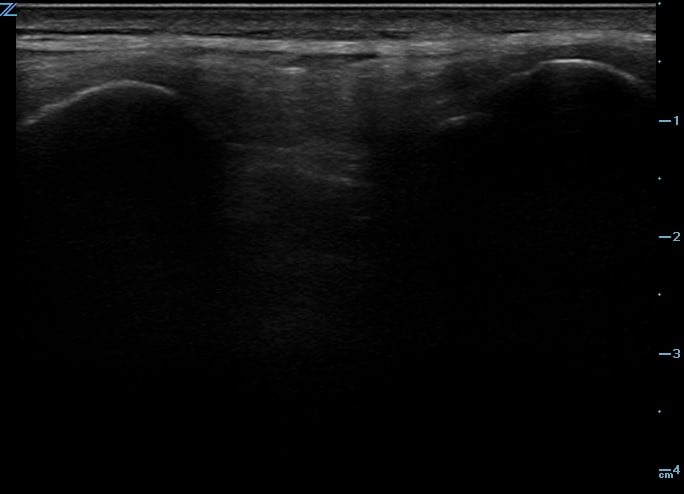

One recommended approach is to start with the probe in transverse position at the level of the sacrum and scan superiorly, sequentially identifying the spinous processes of L5, L4, L3, and L2. In the transverse orientation, spinous processes are seen as small, hyperechoic marks with dense vertical shadowing (Figure 1). With the probe centered over a spinous process, the operator uses a clean towel to wipe off excess gel, and a skin marker to place a vertical hash mark above and below the midline of the probe (Figure 2). Next, the probe is placed in longitudinal orientation over the same spinous processes, with the indicator toward the patient’s head. In this view, spinous processes will appear as wider, hyperechoic areas with distal shadowing (Figure 3). When two or more spinous processes are simultaneously visualized, the space between them is the area available for needle insertion. The skin is marked again, this time with horizontal hash marks extending outward from the midline of the probe (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Ultrasound image of spinous process in transverse plane.

Figure 2. Ultrasound transducer in transverse plane with midline hash marks

Figure 3. Ultrasound image of spinous processes in longitudinal plane.

Figure 4. Ultrasound transducer in longitudinal plane with midline hash marks

With the probe removed, the operator uses the skin marker to create a straight line connecting the vertical hash marks, and another line connecting the horizontal hash marks. This creates a crosshatch, the center of which should be directly above a spinous process (Figure 5). This process of imaging and marking is repeated on the spinous process above or below, creating a second crosshatch. The final step is to draw a vertical line connecting the two crosshatches. (Figure 6 and 7) This vertical line between the hatches identifies the intervertebral space available for needle insertion.

Figure 5. Both hash marks immediately after identification with the ultrasound probe.

Figure 6. Crosshatch identifying the first spinous process

Figure 7. Crosshatches identifying two spinous processes.

While obtaining long-axis images of the spinal column, the proceduralist should identify the widest and most superficial intervertebral space. The chosen space should be inferior to the termination of the conus medularis, which typically ends at the level of L2 in adults.8 In neonates, the conus can extend as low as L4 and may be visualized during image acquisition.9

Limitations

As with any ultrasound application, the skill is operator-dependent. Procedural success may be limited by the skill level of the sonographer, as well as the proceduralist’s experience with performing an LP. The other significant limitation to this technique is the potential for patient movement and repositioning to translate skin markings away from the intended puncture site.

Application in the ED

Lumbar punctures are frequently performed in the Emergency Department,3,7 and it is often possible to perform the procedure successfully without the guidance of imaging. While it is not necessary to incorporate ultrasound into every LP, it has been shown to be of particular benefit with pediatric patients and obese adult patients. As the use of POCUS by Emergency Physicians is increasingly commonplace,10 ultrasound-assisted LP is a natural extension of our skill set, with multiple studies in the literature shown to increase LP success rate, increase first-attempt success rate, reduce the number of traumatic LPs, and shorten the time to successful LP. Ultrasound-assisted LP is a valuable skill that all Emergency Physicians should have in their arsenal.

References

- Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Neuman MI. Risk factors for traumatic or unsuccessful lumbar punctures in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Jun;49(6):762-71.

- Glatstein MM, Zucker-Toledano M, Arik A, et al. Incidence of traumatic lumbar puncture: experience of a large, tertiary care pediatric hospital. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011 Nov;50(11):1005-9.

- Kessler DO, Arteaga G, Ching K, et al. Interns' success with clinical procedures in infants after simulation training. Pediatrics. 2013 Mar;131(3):e811-20.

- Nomura JT, Leech SJ, Shenbagamurthi S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted lumbar puncture. J Ultrasound Med. 2007 Oct;26(10):1341-8.

- Shaikh F, Brzezinski J, Alexander S, et al. Ultrasound imaging for lumbar punctures and epidural catheterisations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f1720.

- Gottlieb M, Holladay D, Peksa GD, et al. Ultrasound-assisted Lumbar Punctures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Jan;26(1):85-96.

- Neal JT, Kaplan SL, Woodford AL, et al. The Effect of Bedside Ultrasonographic Skin Marking on Infant Lumbar Puncture Success: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 May;69(5):610-619.

- Soni NJ, Franco-Sadud R, Schnobrich D, et al. Ultrasound guidance for lumbar puncture. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016 Aug;6(4):358-368.

- Muthusami P, Robinson AJ, Shroff MM. Ultrasound guidance for difficult lumbar puncture in children: Pearls and pitfalls. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(7):822-830.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound guidelines: Emergency, point-of-care and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine [policy statement]. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 May;69(5):e27-e54.

Jacob Holton, MD

Michael Gottlieb, MD

Rush University Medical Center