Cases That Count: Rapid Bedside Diagnosis of a Rare but Dangerous Diagnosis

Questions:

- What sonopathology is demonstrated in these videos?

- What are the ultrasound criteria for this pathology?

- What are the potential pitfalls of this Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) study?

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old G2P1001 woman (6 weeks 1 day pregnant by last menstrual period) presented to the emergency department at midnight with abdominal pain. She had a history of a low transverse Cesarean section three years prior. The day before presentation, she had sudden onset abdominal pain associated with dysuria and flank pain. She was started on nitrofurantoin by her primary physician. She initially felt mildly improved, but then presented at midnight to the emergency department the following day with worsening, sharp, right lower quadrant abdominal pain associated with nausea and lightheadedness.

The patient was notably pale in triage and was immediately transferred to a resuscitation suite. Her blood pressure was 111/64, heart rate 81, and afebrile. On examination, the patient was pale and in mild distress and cool to touch. Her abdomen was distended, diffusely tender, with a healed, low transverse Cesarean section scar.

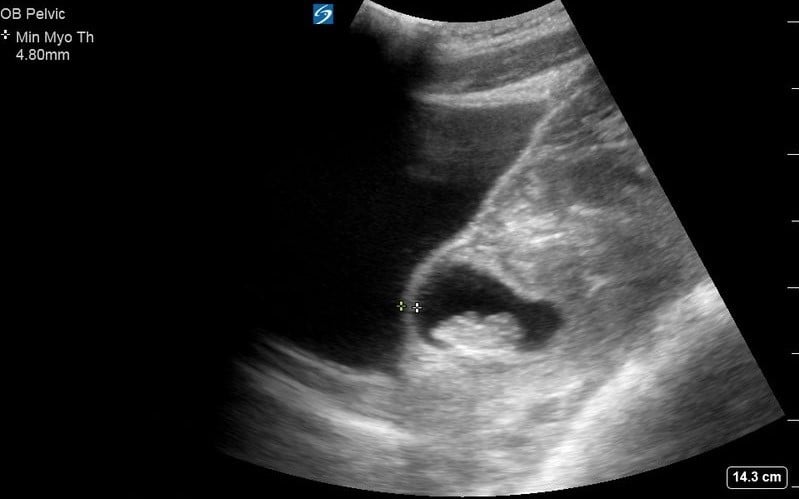

At the same time of the initial emergency physician evaluation, an ultrasound examination using a curvilinear transducer of the right upper quadrant revealed a large amount of intraperitoneal fluid (Figure 1, Video 1). The visualized uterine cavity was empty with mixed echogenicity surrounding the uterus. A bulging abnormality was noted in the anterior myometrium in the lower uterine segment, corresponding to the site of her prior Cesarean section (Figure 2). A gestational sac was visualized in the lower anterior uterine segment with a visible embryo and fetal heart movement. There was a thin amount of tissue between the sac and maternal bladder measuring 4.8 mm (Figure 3, Video 2).

Figure 1. Right upper quadrant ultrasound demonstrating large amount of free fluid.

Figure 2. Transabdominal transverse pelvic ultrasound demonstrating mixed echogenicity surrounding the uterus with a bulging abnormality noted in the anterior myometrium in the lower uterine segment.

Figure 3. Transabdominal sagittal uterus with a gestational sac visualized in the lower anterior uterine segment with a visible embryo and fetal heart movement.

Answers:

1. What sonopathology is demonstrated in these images and videos?

Hemoperitoneum from ruptured Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSP).

2. What are the ultrasound criteria for this pathology?

The ACEP Ultrasound Guidelines outline use of ultrasound in first trimester pregnancy, and therefore emergency physicians should be aware of previously described transvaginal ultrasound diagnostic criteria for CSP including: 1,2,5,7-8,12

- an empty uterine canal

- an empty cervical canal

- a gestational sac between the bladder and the anterior lower segment of the uterus with absent or diminished myometrial thickness between the sac and maternal bladder

- discontinuity in the anterior wall of the uterus on a sagittal view running through the gestational sac

The diagnostic modality of choice of CSP is ultrasound using an endovaginal approach with color flow Doppler and can be confirmed in stable patients by magnetic resonance imaging, or during laparoscopy and/or laparotomy.4,8 In one case series, endovaginal ultrasound diagnosed 94/111 cases with a sensitivity of 84.6% (95% CI 76.3% - 90.5%).4 As in this case, the diagnosis can and has been made by using a transabdominal approach.11

3. What are the potential pitfalls of this Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) study?

The criteria listed above help to distinguish from other diagnoses such as cervical or cervicoisthmic implantation, normal pregnancy with low uterine implantation, or spontaneous abortion in progress.7,12 The use of color Doppler can further confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating peri-trophoblastic perfusion surrounding the gestational sac as compared to a spontaneous abortion, which will lack normal surrounding color doppler flow.2,3,5 In addition, authors have described a negative ‘sliding organ sign’, or the inability to displace the gestational sac with gentle pressure using the endovaginal probe, to help differentiate from a spontaneous abortion or low implanted pregnancy.3 Some authors advise that this technique should be used with caution as it can theoretically provoke vaginal bleeding or rupture.8 It has also been noted that CSP has been mistaken as a fibroid on initial ultrasound evaluation of the pregnancy.9

It is recommended to use a combined endovaginal and abdominal approach to diagnose CSP. However, in using a transabdominal approach alone, a practitioner should suspect the diagnosis if they can identify an embedded mass between the bladder wall and the anterior lower portion of the uterus with thinning of the myometrium between the sac and the bladder.8 Using an abdominal approach with a full bladder can allow for a clearer image of the uterus and the bulging gestational sac in the lower uterine segment and its relation to the scar than images using a vaginal probe.5,8 Finally, it is important to emphasize the requirement of an endomyometrial mantle of at least 8 mm to rule in intrauterine pregnancy.

Summary

Cesarean scar pregnancy is an uncommon form of ectopic pregnancy in which implantation occurs within the myometrial scar tissue of a prior Cesarean section at the anterior, lower uterine segment. Estimated incidence ranges from 1:1800 to 1:2216 pregnancies according to one case series, or approximately 6.1% of all ectopic pregnancies or less than 1% of all pregnancies.3-5 CSP is thought to be the rarest location for ectopic pregnancy, but incidence is increasing, likely due to the rise in number of Cesarean sections and more widespread use of sonography and improved detection.3-8 Complications from CSP include life-threatening hemorrhage, uterine rupture, and hysterectomy.9 In this case, the patient required hysterectomy to control the hemorrhage which has been reported to occur in 2-12.5% of CSP.10

References

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. [policy statement]. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:e27-e54

- Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a Cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000;16:592-593.

- Jurkovik D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, et al. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003;21:220-227.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1373-1381.

- Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2004;23:247-253.

- Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. Int J of Obstet Gynecol 2007;114:253-263.

- Fylstra DL, Pound-Chang T, Miller G, et al. Ectopic pregnancy within a Cesarean delivery scar: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:302-304.

- Maymon R, Halperin R, Mendlovir S, et al. Ectopic pregnancies in caesarean section scars: the 8 year experience of one medical centre. Human Repro 2004;19:278-284.

- Selvaraj L, Rose N, Ramachandran M. Pitfalls in Ultrasound Diagnosis of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2018; 68:164-172

- Collins K, Kothari A. Catastrophic consequences of a ceasarean scar pregnancy missed on ultrasound. Australas J Ultrasound Med 2015; 18:150-156

- Smith A, Ash A, Maxwell D. Sonographic diagnosis of Cesarean scar pregnancy at 16 weeks. J Clin Ultrasound 2007;35:212-215.

- Godin PA, Bassil S, Donnez J. An ectopic pregnancy developing in a previous caesarian section scar. Fertil Steril 1997;67:398-400.

Sophia Bodnar, DO;

Troy Foster, MD

University of Illinois - Chicago