Updated Considerations for Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation

Tristan Beeson, MS4

Rush Medical College

Note: While we are currently facing a temporary shortage of IV fluids in the United States, knowing the basics of IV fluid selection is important for any emergency/critical care physician.

Background

Intravenous fluids (IV) are routinely given in the emergency department (ED) for a wide variety of conditions, in order to replete intravascular volume. Maintaining intravascular volume is essential for achieving adequate tissue perfusion and preventing end-organ damage. To this end, IV fluids have been in use for several centuries. The first recorded use of IV fluids was in 1831 during an outbreak of cholera in Sutherland, England.1 Fluids with varying compositions were subsequently developed in the following decades. Lactated Ringer’s (LR) was discovered in 1883 by Sydney Ringer when a solution that was accidentally made with tap water instead of distilled water was found to sustain cardiac activity for longer periods in frog hearts.2 Lactate was later added by Alexis Hartmann in 1930 to mitigate acidosis. Normal saline (NS) was likely first formulated by Joseph Hamburger in 1896, who found that a 0.9% sodium-chloride solution had a similar freezing point to human blood compared to other fluids with similar tonicities.3 More recently, Plasma-Lyte was developed by Baxter International in 1982 in order to make a balanced electrolyte solution that would be very similar to the physiologic composition of plasma.4.

Having several options from which to choose has led to ongoing debates surrounding the proper selection and usage of IV fluids. Given that intravascular resuscitation is a cornerstone of management of life-threatening conditions such as sepsis, traumatic blood loss, and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), it is important for emergency/critical care physicians to make informed decisions about the use of this crucial interventional tool.

Crystalloid vs. Colloid Solutions

Fluid types fall under general categories, such as crystalloid (eg, NS, LR, Plasma-Lyte) or colloid (eg, albumin, FFP, dextran) solutions. Crystalloid solutions contain water and electrolytes which expand intravascular volume and increase hydrostatic pressure. By contrast, colloid solutions contain large molecules that increase oncotic pressure and pull fluid into the vasculature.

Colloid solutions are more expensive and typically less available than crystalloid solutions. In theory, the use of colloids was justified by the idea that less volume was required to achieve the same effect as crystalloids.5 However, evidence from several studies have shown that, in practice, using colloid solutions does not decrease the total amount of fluid needed for resuscitating critically-ill patients, and certain colloids, such as hydroxyethyl starch, have greater rates of adverse effects.6-8 Explanations for this finding include a revised Starling equation, which emphasizes hydrostatic pressure as a more dominant force than oncotic pressure.9 Additionally, the loss of vascular glycocalyx integrity in critical illness, like sepsis, may lead to a net driving force favoring filtration of fluid out of blood vessels.10 Certain colloids, such as albumin, still have an evidence-based role in specific pathologies, like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome.5 However, crystalloids are now generally the favored solutions for usage in fluid resuscitation.

Crystalloid Composition

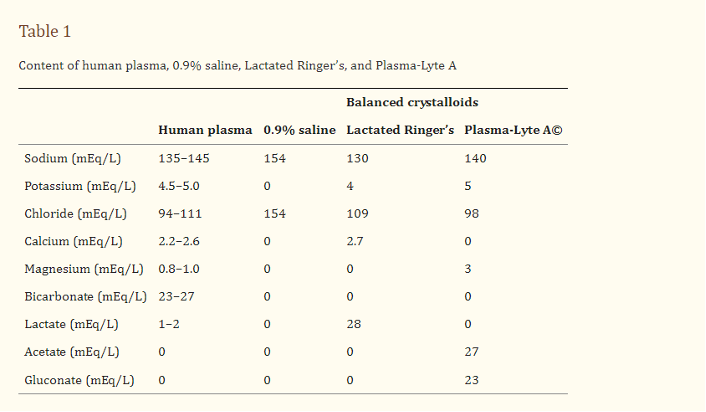

Fluids can further be subdivided into three categories according to their tonicity relative to blood: hypotonic, isotonic, or hypertonic. Hypotonic fluids (eg, 0.45% NS, 5% dextrose) and hypertonic fluids (eg, 3% NS) cause cellular fluid shifts and are only used in select cases, such as severe hypo- or hypernatremia. Isotonic fluids are used for resuscitation in most cases, because they replenish intravascular volume without causing fluid shifts. The three main isotonic crystalloids are 0.9% NS, LR, Plasma-Lyte, and the composition of each is shown below:

Figure 1: Composition of several crystalloid solutions compared to human plasma. Taken from Self et al.11.

It is important to highlight several key differences between these fluids. NS has supra-physiologic concentrations of both Na and Cl (154 mEq/L of each), an acidic pH of 5.8, and an osmolarity of 308 mOsm/L, making it just slightly hypertonic compared to plasma (275-295 mOsm/L).12 LR has near physiologic levels of Na, K, Cl, and Ca with the addition of 28 mEq/L of lactate and an initially isotonic osmolarity of 273 mOsm/L.12 Plasma-Lyte also contains physiologic levels of electrolytes, with the addition of sodium acetate and sodium gluconate, and an isotonic osmolarity of 294 mOsm/L.12.

Fluid Selection

The IV fluid of choice for resuscitation is an active area of investigation. For the past several decades in the United States, 0.9% NS has been the most widely used isotonic crystalloid.13 NS is generally safe and effective; however, it has been well established that the infusion of large amounts of NS can cause a hyperchloremic, non-anion gap metabolic acidosis and worsening renal function due to the high levels of chloride in the solution.14-17 The clinical relevance of this effect has been unclear for some time. While several smaller studies showed worse clinical outcomes with high-volume saline infusion18, results from a large, multicenter, randomized trial called the SPLIT study in 2015 showed no significant difference in AKI rates between NS and Plasma-Lyte in patients admitted to the ICU.19.

More recently in 2018, the results of two large, single center studies provided substantive evidence to suggest that balanced crystalloids may be preferential to NS.20,21 The SALT-ED trial evaluated hospital-free days and major adverse kidney events within 30 days among non-ICU patients who were assigned to receive either balanced crystalloid (LR or Plasma-Lyte) or 0.9% NS. There was no difference in hospital-free days between the two groups, but balanced crystalloids resulted in a lower incidence of major adverse kidney events within 30 days (4.7% vs 5.6%; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.95; p=0.01).20 Similarly, the SMART trial compared balanced crystalloids versus saline in patients admitted to the ICU. The authors found a decrease in the number of major adverse kidney events in the balanced crystalloid group (14.3%) compared to the saline group (15.4%), which was statistically significant (95% CI, 0.84 to 0.99; p=0.04). There was also a decrease in hospital mortality at 30 days from 10.3% in the balanced-crystalloids group compared to 11.1% in the saline group (p=0.06).21 While the absolute difference in mortality and kidney events between groups was not large, the sheer quantity of fluids given annually does make these results clinically significant for patient outcomes.

One confounding factor that may explain differences between study results is the total fluid volume administered. The median amount of fluid given in both groups in the SPLIT trial was a relatively low 2.0 L.19 While the SMART trial also had a low median fluid given to its groups (~1 L each), subgroup analyses revealed that the difference between the rate of the primary outcome between groups was greater among patients who received larger volumes of fluid.21 Indeed, the most profound improvements in mortality were found among patients with sepsis, who typically receive large quantities of fluids. In the SMART trial, patients with sepsis had a decrease of in-hospital mortality from 29.4% with saline to 25.2% with balanced crystalloids (adjusted odds ratio, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.97; p= 0.02). Therefore, the benefits of balanced crystalloids seem to take effect mainly when large volumes of fluid are being infused. This idea is challenged, however, by data from the BaSICS trial, which was published in JAMA in 2021. The results of this trial showed no difference in 90-day mortality among ICU patients in Brazil between balanced crystalloids and NS who were administered a robust volume of fluids.22.

Other studies that have analyzed the use LR and NS for specific conditions have shown that LR is generally equivalent or superior to NS. LR has been shown to decrease mortality rates in patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis compared to NS.23 Another study demonstrated that a chloride lowering strategy was beneficial in sepsis patients.24 In patients diagnosed with pancreatitis, LR was found to decrease the rate of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and CRP levels25, as well as the rate of ICU admissions and overall length of hospital stay.26 A subgroup analysis from the SALT-ED and SMART trials found a decrease in time to resolution of DKA and insulin discontinuation in the LR group.27 Patients with clinical signs of dehydration may also benefit from balanced crystalloids over NS.28 No significant difference in outcomes between isotonic crystalloid fluids has been identified in trauma patients.29

Several misconceptions about LR have previously discouraged physicians from using this fluid more frequently. One misconception is that the potassium contained in LR can cause or further exacerbate hyperkalemia, especially in patients with renal dysfunction. While LR does typically contain 4 mEq/L of potassium, infusion of large amounts of this fluid should theoretically bring the serum concentration towards 4 mEq/L, which would result in a decrease serum potassium concentration in hyperkalemic patients.30 Additionally, the volume of distribution of potassium is high, so it tends to equilibrate among extracellular and intracellular spaces.31 It would, therefore, require a massive infusion of LR in order to cause a significant change in the serum potassium concentration. Lastly, a few studies have shown that NS, rather than LR, is more prone to causing hyperkalemia, even in patients with renal failure.32-34 To explain this effect, it has been suggested that the metabolic acidosis caused by NS can pull potassium into the intravascular space, leading to elevated serum levels, while the alkalinizing effects of LR actually drive potassium intracellularly, thus decreasing serum potassium levels.35

Another concern surrounding LR is that the 28 mEq/l of lactate found in the solution may worsen lactic acidosis. There are several lines of reasoning which argue against this idea. First, lactate is the conjugate base of lactic acid and is therefore a byproduct, not the cause of, lactic acidosis. Second, LR contains sodium lactate, which is metabolized into bicarbonate, and does not increase lactic acid levels.36 Lastly, empirical data demonstrates that while infusions of LR may increase serum lactate levels, it also increases pH and bicarbonate concentrations, therefore improving acidemia.37

There are a few situations in which LR is either an inferior choice or requires additional considerations. In patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), evidence suggests that balanced crystalloids are associated with increased mortality rate compared to NS.38,39 LR is slightly hypotonic compared to NS, which may contribute to the development of cerebral edema in this population. Additionally, patients who have received burn injuries may benefit more from dextrose and normal saline, compared to LR alone, which may be lacking the glucose and sodium these patients require.40 Lastly, LR does contain 2.7 mEq/L of calcium, which may cause calcium precipitation when mixed with other medications (such as ceftriaxone) or blood products. Therefore, ceftriaxone and LR, if administered together, should be given through separate IV lines.41 Similarly, another study recommended that eight other medications (ciprofloxacin, cyclosporine, diazepam, ketamine, lorazepam, nitroglycerin, phenytoin, and propofol) out of a total 94 studied, should be administered through a separate line if LR is also infusing.42 The citrate used in blood products may also cause calcium precipitation with LR, and should likewise also be given through separate lines.43

Fluid Resuscitation Strategies

While the type of fluid administered is important to consider, physicians should also give careful thought to the timing and quantity of fluid administered. The traditional approach to fluid resuscitation involves an initial trial bolus of fluids with additional fluids being given based on the patient’s hemodynamic response. This protocol has limitations. Evidence suggests that the effects of this fluid bolus typically last around 120 minutes, depending on the quantity of fluid infused, and merely reflects a temporary increase in cardiac output and vascular hydrostatic pressure, rather than a definitive improvement in hemodynamic parameters.44

More advanced resuscitation strategies have focused on fluid responsiveness to dictate fluid administration. The data supports that the passive leg raise technique and noninvasive measurements of cardiac output (eg, pulse pressure variation) are accurate methods for determining fluid responsiveness.45 However, resuscitation strategies based on fluid responsiveness have not demonstrated significant changes in mortality rates.46 It is interesting to note another study which revealed that about 90% of healthy volunteers will respond to a fluid bolus with an increase in cardiac output.47 This might suggest that most people exist in a naturally fluid responsive state that does not require fluid administration.12

Furthermore, overly aggressive fluid resuscitation strategies may cause harm. More conservative fluid management has been shown to reduce rates of pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and acute kidney injury associated with more liberal fluid management strategies.48 The injurious effects of excess fluid administration are likely due to pooling of fluid in the venous system, leading to an increase in CVP, and then subsequent extravasation of fluid into interstitial tissues.12 Hypotensive fluid resuscitation strategies have already been successfully utilized in patients with traumatic injuries.49 Administration of the minimum amount of fluid necessary to maintain end organ perfusion decreased coagulopathy, early postoperative death, and improved outcomes in several studies on trauma patients.50-51

The results of the CLOVERS trial were recently published in NEJM in 2023. This study was conducted across 60 U.S. centers and compared the efficacy of a restrictive fluid strategy with early vasopressor use versus a liberal fluid strategy with delayed vasopressor use in patients with sepsis-induced hypotension.52 There was no difference in death from any cause before discharge home by day 90 between the restrictive fluid group (14.0%) and the liberal fluid group (14.9%) (95%CI, -4.4 to 2.6; p=0.61). This data further highlights the idea that restrictive fluid strategies can be as effective as liberal fluid strategies and may avoid the associated adverse effects of large volume resuscitation.

The ideal fluid resuscitation strategy has yet to be determined and will likely continue to be investigated for quite some time. Ultimately, even the best fluid management protocols are simply temporary measures which do not fix the underlying cause of the patient’s hemodynamic instability. Physicians should prioritize the identification and treatment of the illness source, regardless of the specific fluid strategy which is implemented.12

Conclusion

Intravenous fluids have been and will continue to be vital, life saving measures for patients requiring resuscitation. Many different fluid options exist for physicians to choose from. Crystalloid solutions are generally preferable to colloid solutions, with the exception of select cases in which colloids are still used. Among the isotonic crystalloid solutions, normal saline contains a supraphysiologic amount of sodium and chloride and is slightly hypertonic, compared to lactated Ringer’s and Plasma-Lyte which are balanced solutions that more closely resemble physiologic concentrations of electrolytes.

Normal saline has been the standard fluid used for resuscitation in the U.S. for several decades, despite its ability to cause a hyperchloremic, non-anion gap metabolic acidosis. Several studies have been published in recent years which suggest that balanced crystalloids are either as effective or slightly better than normal saline for patient mortality and kidney functioning, especially when infused in large quantities. Previous hesitation to use lactated Ringer’s was based on fears of it causing lactic acidosis and hyperkalemia, both of which are unfounded. Lactated Ringer’s has ample data to support its use in resuscitation, especially in critically ill patients with sepsis/SIRS, pancreatitis, and DKA. The only major exception to this is in patients with traumatic brain injuries, where normal saline has better outcomes. Due to the possibility of calcium precipitation, lactated Ringer’s should probably be infused in a separate IV line when co-administered with certain medications or blood products.

Previous fluid resuscitation strategies centered around a fluid challenge, while modern strategies have focused on fluid responsiveness. There is limited evidence that any particular protocol is superior to another. Giving too much fluid can also be problematic. Fluid restrictive strategies are being actively studied and have been shown to be especially effective in trauma patients. Ultimately, the choice and amount of fluid administered is likely less important than correctly identifying and managing the underlying pathology.

References

- Cosnett JE. The origins of intravenous fluid therapy. Lancet. 1989 Apr 8;1(8641):768-71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92583-x. PMID: 2564573.

- Baskett TF. The resuscitation greats: Sydney Ringer and lactated Ringer's solution. Resuscitation. 2003 Jul;58(1):5-7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00209-0. PMID: 12867303.

- Awad S, Allison SP, Lobo DN. The history of 0.9% saline. Clin Nutr. 2008 Apr;27(2):179-88. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.01.008. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18313809.

- Dawson R, Wignell A, Cooling P, et al. Physico-chemical stability of Plasma-Lyte 148® and Plasma-Lyte 148® + 5% Glucose with eight common intravenous medications. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019 Feb;29(2):186-192. doi: 10.1111/pan.13554. Epub 2019 Jan 8. PMID: 30472805.

- Vincent JL, Russell JA, Jacob M, et al. Albumin administration in the acutely ill: what is new and where next? Crit Care. 2014 Jul 16;18(4):231. doi: 10.1186/cc13991. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2014;18(6):630. Roca, Ricard Ferrer [corrected to Ferrer, Ricard]. PMID: 25042164; PMCID: PMC4223404.

- Perel P, Roberts I, Ker K. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Feb 28;(2):CD000567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub6. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Aug 03;8:CD000567. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub7. PMID: 23450531.

- Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 10;370(15):1412-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305727. Epub 2014 Mar 18. PMID: 24635772.

- Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 27;350(22):2247-56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040232. PMID: 15163774.

- Woodcock TE, Woodcock TM. Revised Starling equation and the glycocalyx model of transvascular fluid exchange: an improved paradigm for prescribing intravenous fluid therapy. Br J Anaesth. 2012 Mar;108(3):384-94. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer515. Epub 2012 Jan 29. PMID: 22290457.

- Chelazzi C, Villa G, Mancinelli P, et al. Glycocalyx and sepsis-induced alterations in vascular permeability. Crit Care. 2015 Jan 28;19(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0741-z. PMID: 25887223; PMCID: PMC4308932.

- Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al. Saline versus balanced crystalloids for intravenous fluid therapy in the emergency department: study protocol for a cluster-randomized, multiple-crossover trial. Trials. 2017 Apr 13;18(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1923-6. PMID: 28407811; PMCID: PMC5390477.

- Gordon D, Spiegel R. Fluid Resuscitation: History, Physiology, and Modern Fluid Resuscitation Strategies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2020 Nov;38(4):783-793. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2020.06.004. Epub 2020 Jul 21. PMID: 32981617.

- Myburgh JA, Mythen MG. Resuscitation fluids. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 26;369(13):1243-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208627. PMID: 24066745.

- Hartmann AF, Senn MJ. STUDIES IN THE METABOLISM OF SODIUM r-LACTATE. I. RESPONSE OF NORMAL HUMAN SUBJECTS TO THE INTRAVENOUS INJECTION OF SODIUM r-LACTATE. J Clin Invest. 1932 Mar;11(2):327-35. doi: 10.1172/JCI100414. PMID: 16694041; PMCID: PMC435816.

- Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, et al. Etiology of metabolic acidosis during saline resuscitation in endotoxemia. Shock. 1998 May;9(5):364-8. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199805000-00009. PMID: 9617887.

- Bullivant EM, Wilcox CS, Welch WJ. Intrarenal vasoconstriction during hyperchloremia: role of thromboxane. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jan;256(1 Pt 2):F152-7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.1.F152. PMID: 2912160.

- Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Glassford N, et al. Chloride-liberal vs. chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration and acute kidney injury: an extended analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Feb;41(2):257-64. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3593-0. Epub 2014 Dec 18. PMID: 25518951.

- Semler MW, Kellum JA. Balanced Crystalloid Solutions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Apr 15;199(8):952-960. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201809-1677CI. PMID: 30407838; PMCID: PMC6467313.

- Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R, et al. Effect of a Buffered Crystalloid Solution vs Saline on Acute Kidney Injury Among Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: The SPLIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015 Oct 27;314(16):1701-10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12334. Erratum in: JAMA. 2015 Dec 15;314(23):2570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15495. PMID: 26444692.

- Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Noncritically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 1;378(9):819-828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711586. Epub 2018 Feb 27. PMID: 29485926; PMCID: PMC5846618.

- Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 1;378(9):829-839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584. Epub 2018 Feb 27. PMID: 29485925; PMCID: PMC5846085.

- Zampieri FG, Machado FR, Biondi RS, et al. Effect of Intravenous Fluid Treatment With a Balanced Solution vs 0.9% Saline Solution on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients: The BaSICS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Aug 10;326(9):1–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11684. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34375394; PMCID: PMC8356144.

- Raghunathan K, Shaw A, Nathanson B, et al. Association between the choice of IV crystalloid and in-hospital mortality among critically ill adults with sepsis*. Crit Care Med. 2014 Jul;42(7):1585-91. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000305. PMID: 24674927.

- Shaw AD, Raghunathan K, Peyerl FW, et al. Association between intravenous chloride load during resuscitation and in-hospital mortality among patients with SIRS. Intensive Care Med. 2014 Dec;40(12):1897-905. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3505-3. Epub 2014 Oct 8. PMID: 25293535; PMCID: PMC4239799.

- Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, et al. Lactated Ringer's solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Aug;9(8):710-717.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.026. Epub 2011 May 12. PMID: 21645639.

- Lee A, Ko C, Buitrago C, et al. Lactated Ringers vs Normal Saline Resuscitation for Mild Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2021 Feb;160(3):955-957.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.044. Epub 2020 Nov 4. PMID: 33159924.

- Self WH, Evans CS, Jenkins CA, et al. Clinical Effects of Balanced Crystalloids vs Saline in Adults With Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Subgroup Analysis of Cluster Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2024596. doi:

- Hasman H, Cinar O, Uzun A, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing the effect of rapidly infused crystalloids on acid-base status in dehydrated patients in the emergency department. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(1):59-64. doi: 10.7150/ijms.9.59. Epub 2011 Nov 23. PMID: 22211091; PMCID: PMC3245412.

- Kaczynski J, Wilczynska M, Hilton J, et al. Impact of crystalloids and colloids on coagulation cascade during trauma resuscitation - a literature review. Emerg Med Health Care. 2013;1:1.

- Piper GL, Kaplan LJ. Fluid and electrolyte management for the surgical patient. Surg Clin North Am. 2012 Apr;92(2):189-205, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.01.004. Epub 2012 Feb 9. PMID: 22414407.

- Winkler AW, Smith PK. The apparent volume of distribution of potassium injected intravenously. J Biol Chem. 1938;124(3):589-598.

- Khajavi MR, Etezadi F, Moharari RS, et al. Effects of normal saline vs. lactated ringer's during renal transplantation. Ren Fail. 2008;30(5):535-9. doi: 10.1080/08860220802064770. PMID: 18569935.

- Modi MP, Vora KS, Parikh GP, et al. A comparative study of impact of infusion of Ringer's Lactate solution versus normal saline on acid-base balance and serum electrolytes during live related renal transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012 Jan;23(1):135-7. PMID: 22237237.

- O'Malley CMN, Frumento RJ, Hardy MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of lactated Ringer's solution and 0.9% NaCl during renal transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2005 May;100(5):1518-1524. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000150939.28904.81. PMID: 15845718.

- Farkas, Josh. “Myth-Busting: Lactated Ringers Is Safe in Hyperkalemia, and Is Superior to NS.” EMCrit Project, 25 Feb. 2018, emcrit.org/pulmcrit/myth-busting-lactated-ringers-is-safe-in-hyperkalemia-and-is-superior-to-ns/.

- Gladden LB. Lactate metabolism: a new paradigm for the third millennium. J Physiol. 2004 Jul 1;558(Pt 1):5-30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058701. Epub 2004 May 6. PMID: 15131240; PMCID: PMC1664920.

- Zitek T, Skaggs ZD, Rahbar A, et al. Does Intravenous Lactated Ringer's Solution Raise Serum Lactate? J Emerg Med. 2018 Sep;55(3):313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.05.031. Epub 2018 Jul 20. PMID: 30037514.

- Zampieri FG, Machado FR, Biondi RS, et al. Effect of Intravenous Fluid Treatment With a Balanced Solution vs 0.9% Saline Solution on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients: The BaSICS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Aug 10;326(9):1–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11684. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34375394; PMCID: PMC8356144.

- Rowell SE, Fair KA, Barbosa RR, et al. The Impact of Pre-Hospital Administration of Lactated Ringer's Solution versus Normal Saline in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016 Jun 1;33(11):1054-9. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3478. Epub 2016 Feb 25. PMID: 26914721; PMCID: PMC4892214.

- Bedi MK, Sarabahi S, Agrawal K. New fluid therapy protocol in acute burn from a tertiary burn care centre. Burns. 2019 Mar;45(2):335-340. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.03.011. Epub 2019 Jan 25. PMID: 30686697.

- Burkiewicz JS. Incompatibility of ceftriaxone sodium with lactated Ringer's injection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999 Feb 15;56(4):384. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.4.384. PMID: 10690221.

- Vallée M, Barthélémy I, Friciu M, et al. Compatibility of Lactated Ringer's Injection With 94 Selected Intravenous Drugs During Simulated Y-site Administration. Hosp Pharm. 2021 Aug;56(4):228-234. doi: 10.1177/0018578719888913. Epub 2019 Nov 18. PMID: 34381254; PMCID: PMC8326865.

- Singh S, Kerndt CC, Davis D. (2023, August 14). Ringer’s Lactate. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500033/

- Glassford NJ, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R. Physiological changes after fluid bolus therapy in sepsis: a systematic review of contemporary data. Crit Care. 2014 Dec 27;18(6):696. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0696-5. PMID: 25673138; PMCID: PMC4331149.

- Bentzer P, Griesdale DE, Boyd J, et al. Will This Hemodynamically Unstable Patient Respond to a Bolus of Intravenous Fluids? JAMA. 2016 Sep 27;316(12):1298-309. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12310. PMID: 27673307.

- Ehrman RR, Gallien JZ, Smith RK, et al. Resuscitation Guided by Volume Responsiveness Does Not Reduce Mortality in Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Explor. 2019 May 23;1(5):e0015. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000015. PMID: 32166259; PMCID: PMC7063966.

- Miller J, Ho CX, Tang J, et al. Assessing Fluid Responsiveness in Spontaneously Breathing Patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2016 Feb;23(2):186-90. doi: 10.1111/acem.12864. Epub 2016 Jan 14. PMID: 26764894.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network; Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 15;354(24):2564-75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. Epub 2006 May 21. PMID: 16714767.

- Ball CG. Damage control resuscitation: history, theory and technique. Can J Surg. 2014 Feb;57(1):55-60. doi: 10.1503/cjs.020312. PMID: 24461267; PMCID: PMC3908997.

- Morrison CA, Carrick MM, Norman MA, et al. Hypotensive resuscitation strategy reduces transfusion requirements and severe postoperative coagulopathy in trauma patients with hemorrhagic shock: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma. 2011 Mar;70(3):652-63. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e77ea. PMID: 21610356.

- Bickell WH, Wall MJ Jr, Pepe PE, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994 Oct 27;331(17):1105-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701. PMID: 7935634.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Prevention and Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury Clinical Trials Network; Shapiro NI, Douglas IS, Brower RG, et al. Early Restrictive or Liberal Fluid Management for Sepsis-Induced Hypotension. N Engl J Med. 2023 Feb 9;388(6):499-510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212663. Epub 2023 Jan 21. PMID: 36688507; PMCID: PMC10685906.