Medical Considerations for Law Enforcement in Mass Casualty Incidents

Shane Wheeler BA, AAS-P, FP-C, NRP

Chief, Mount Hope Fire Department

Health and Safety Director Summit Bechtel National Scout Reserve

Deputy Emergency Manager Officer and Special Response Incident Commander, National and World Scout Jamborees 2013, 2017, 2019

When the sounds of human agony replace the sound of gunfire, police officers are often left unprepared to manage civilian casualties. Dispatch guidelines, response nimbleness, and the courageous nature of law enforcement often place police officers on the scene first at mass casualty incidents. During a mass casualty event, overburdened communication, no clear incident command, and blocked access often delay EMS, leaving police officers with little or no other choice but to care for and transport the injured in police vehicles.

In the Aurora Theater shooting, 27 people were transported via police cars. 28 minutes elapsed between the arrival at the scene of the fire battalion chief in control of emergency medical services and contact with the police lieutenant in charge of law enforcement issues ("Aurora Theater Shooting Report," 2014). The Pulse Night Club Shooting resulted in officers and deputies placing injured victims in the beds of their trucks and back seats of their cars and driving them to the hospital (Straub et al., n.d.).

At the recent non-violent, mass-casualty incidents such as Astroworld, security carried casualties, including three in cardiac arrest, to a handful of on-site medical staff (Twitter et al., 2021).

EMS staff shortages and hospital overcrowding has recently reduced ambulance availability to respond to events.

Law enforcement has an essential role in casualty survival, whether by design or circumstances. This article highlights how law enforcement agency medical advisors should consider preparing police officers for mass casualty incidents.

Training, planning, and equipping police officers in triage and life-saving medical care can significantly reduce mortality at an MCI incident. Hemorrhage accounts for 40% of trauma deaths worldwide (Curry et al., 2011). Hypoxia and airway mismanagement are known to contribute to 34% of pre-hospital trauma deaths (Khan et al., 2011). Data on active shooter events like Pulse Nightclub shooting reveal a significant number of torso injuries (Smith et al., 2018). Armed with such data, many law enforcement agencies train their officers for these instances. However, often law enforcement medical training programs fall short on triage instruction.

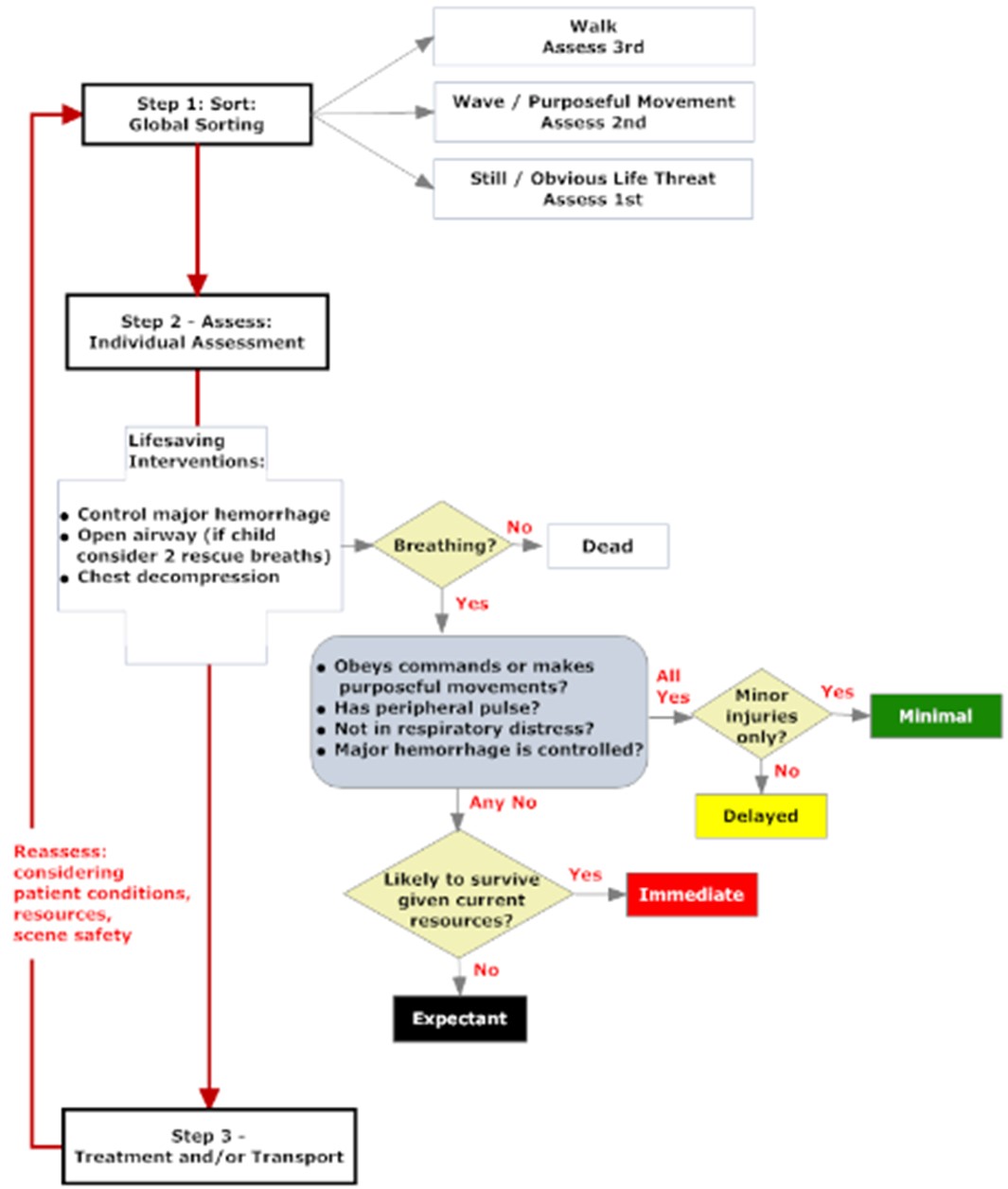

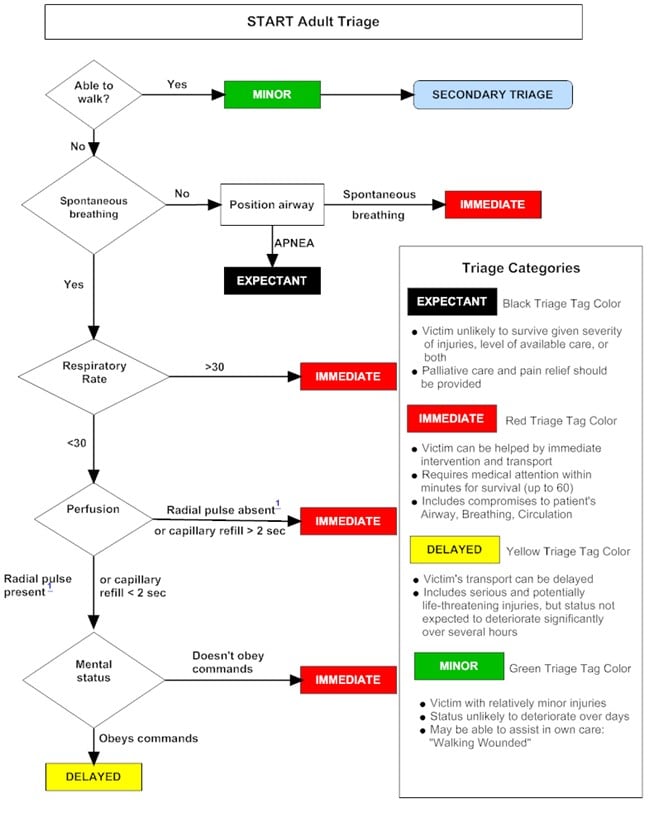

Triage methods such as START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment), and SALT (Sort Assess Lifesaving Interventions Treatment and Transport) are designed to quickly identify casualties that are most in need of care and transport. Training police officers to use START or SALT triage methods will ensure that the injured receive care based on the acuity and survivability of their injuries.

Many law enforcement agencies participate in mass casualty drills, but rarely do the scenarios place police officers at the center of the medical response. Law enforcement and other exercise participants should collaborate to ensure that drills cover triage and medical care by police officers. Regular practice and critique of response and contingency plans are also paramount. Contingency plans are an essential part of any pre-plan; training for plan B, C, or the Z situation prepares police officers for the reality that they will most likely have to deliver some degree of medical care during a mass casualty event.

Along with training, the importance of equipping police officers with mass casualty supplies to render aid to multiple patients can't be overstated. Many officers now carry IFAKs to treat themselves or their partners. However, these small kits are insufficient to treat the numerous victims of a mass casualty event. Also, if medical supplies are used on MCI victims, then the officer is left without the ability to care for themselves in an unsafe situation. Numerous fully stocked commercial products are available for purchase for under $1000.00. Agencies can also construct a mass care kit themselves often for less money.

My recommendations for a mass casualty kit are: a medium-size duffle or backpack style bag filled with 12 one-gallon Ziploc bags each containing two tourniquets, two vented chest seals, 1 Israeli, Oleas or other compression type bandage, wound packing gauze (hemostatic or otherwise), 1 nasopharyngeal airway 28Fr w/ lube, and a pair of trauma shears. The Ziploc bags can be distributed to other responders, by-standers, and the casualty for application. The duffle bag is a convenient throw over your shoulder carrier that can be stowed in the cargo area of the police vehicle.

In closing, medical advisement on MCI response for police agencies should focus on the reality of these situations. Training and equipping police officers to meet the expectations of total response capability and competency regardless of the call is necessary for modern policing.