Anterior Knee Pain - A Guide and Differential Diagnosis

Nicholas Cochran-Caggiano, MD, MS, PGY2

SUNY Upstate, Dept. of Emergency Medicine

Marissa Smith, MD, MS

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics

SUNY Upstate, Dept. of Emergency Medicine

Paul Klawitter, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Fellowship Director- Sports Medicine

SUNY Upstate, Dept. of Emergency Medicine

Case

A 14-year-old male cross-country runner and baseball player presents to the sports medicine clinic for recurrent right anterior knee pain. He reports that, for approximately six months, he has had aching pain superior to his patella. He does not recall any specific injury occurring to the knee. His pain is most severe during periods of prolonged sitting. He first noticed it while at a movie theater. It was particularly bad on a cross-country flight. He notices pain and clicking while running, and he has been unable to train for the upcoming cross-country season. He reports that on a few occasions, the knee has painlessly “buckled.” He was able to walk immediately after without difficulty. He has not had any noticeable swelling of the knee. He has seen his pediatrician, who recommended rest and NSAIDs for a few weeks, but he felt that he has had little to no improvement in that time. He is hopeful that you will be able to relieve his pain.

He has no significant medical history. He is limited by pain but does not endorse weakness. There is no change in sensation described. His pain is unilateral, with no pain to the left knee. He has never had this pain before six months ago. There is no radiation.

On examination, there is no visible or palpable swelling. He has full ROM in extension flexion bilaterally, though with crepitus on extension of the right knee. There is tenderness to palpation of the quadriceps tendon, as well as the medial patellar facet. No patellar apprehension or abnormal laxity. Patella tendon is not tender. No laxity with varus and valgus stress, negative Lachman’s and negative McMurray’s. No pain along the medial or lateral joint line. Strength 5/5 with flexion and extension bilaterally. Gait is non-antalgic.

Differential Diagnosis

Patellofemoral Syndrome (PFS)/Idiopathic anterior knee pain syndrome

Quadriceps tendinopathy

Osteochondritis Dessicans

Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease

Sindig-Larsen Johansson Disease

Discussion

Anterior knee pain (AKP) is a common complaint in primary care offices, emergency departments, and sports medicine clinics. There is a broad differential, which can include tendinopathy, bursitis, synovial plica syndrome, idiopathic anterior knee pain syndrome, as well as osseous malignancy and referred pain. Age is critical for ruling in, or out, certain diagnoses, as well. In pediatric patients, it is important to also consider pathology seen in skeletally immature athletes, including Osgood-Schlatter, Sinding-Larsson-Johansson and bipartite or multipartite patella and juvenile osteochondritis disease. In adults, the differential may broaden to also include osteoarthritis, the most common cause, or osteochondritis dissecans. Patellar dislocation is the only common traumatic etiology of chronic anterior knee pain.1

AKP affects up to 40% of adolescent athletes and is significantly more common in females than males.1,2 Overall, it affects >20% of the general population nationwide and is associated with poorer quality of life. Persistent pain has been associated with depression and represents a significant loss of productivity, both directly and indirectly.1,3

The differential diagnosis for painless giving way of the joint should include a transient patellar malposition or subluxation, a trapped synovial plica, an unstable cartilage flap, or any other ligamentous or meniscal instability. Post-surgical patients require additional considerations.1

Clinical Exam

Careful inspection for alignment, displacement, and atrophy is important before more focused assessment. Gait, genu valgum, genu varum, and joint laxity and rotation are all important characteristics which may direct further investigation. Q-angle, the vector of quadriceps pull, has been suggested as possibly helpful for assessment of patellofemoral syndrome. Crepitus is not specific for any one condition and is often insignificant. Referred pain from the back, hip, or pelvis must always be considered.1,4 It is important to localize the pain both with dynamic activity and point tenderness. Anterior knee pain grossly breaks down to retro patellar or peripatellar in most patients (Osgood-Schlatter breaks this mold).1 Isolated muscle weakness can be helpful to identify referred pain as well as specific AKP etiologies. There are numerous specific tests which may help elucidate specific diagnoses suggested by the aforementioned findings.

Patella-femoral syndrome/idiopathic anterior knee pain

This patient’s symptoms clearly fit this vaguely named condition, referring to a condition causing pain around or behind the patella, particularly with activities that compress the patellofemoral joint. It represents the most common cause of knee pain in young athletes. Commonly taught as a disease of adolescents, it remains a common cause of anterior knee pain through adulthood and may precede the onset of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Incidence is as high as 6%.6 Pain is often non-specific and is generally activity-related, being exacerbated by activities such as with squatting, walking up and down stairs, or jumping. Pain with prolonged sitting, the so-called “theatre sign”, is also a classic presenting symptom.

While poorly understood, biomechanical and anatomical contributions are likely part of the etiology of this syndrome. The largest meta-analysis to date of biomechanical findings related to PFS identified that differences in control of quadriceps and hamstrings, tightness of the hamstrings and weakness of quadriceps or hamstrings are correlated with patellofemoral pain. There is also growing evidence that weakness of the hip abductors and extensors play a part in patellar control, which can contribute to this pain syndrome. In addition to the pain, patients may report catching, locking, or giving way. These patients should be assessed for asymmetry of the patella or quadriceps, joint effusion, gait disturbance, or other suggestions of referred pain. Good clinical assessment for PFS should include inspection for muscle atrophy and alignment of the patella. Evaluating patellar glide, patellar tracking (such as the J sign) can also help support this diagnosis. Tenderness to palpation may or may not be present but, if present, can often be noted at the patellar facets or at the femoral condyles.1 Strength testing of quadriceps, hip abduction, and hip extension should be noted. Functional weakness, such as seen with squatting or single leg press, should also be included in evaluation. Clustering of these physical exam findings has been suggested as a means of improving the low sensitivity and specificity of the previously described methods. The described clusters have been suggested to be 93% specific and 96% sensitive.4 While imaging is not routinely indicated, as this is often a clinical diagnosis, use of x-ray and other imaging can help support the diagnosis and rule out other potential causes of pain.5 Musculoskeletal ultrasound (US) is increasingly useful, and effusions, muscle volume, and tendon thicknesses have all been shown to be markers of potential value in the investigation of PFS.4

Treatment initially consists of rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy (PT). The purpose of PT is to strengthen hip flexors, trunk, and knee muscle groups and is frequently required to allow the patient to return to higher levels of physical activity. Isolated hip strengthening has been shown to be equivalent to traditional knee strengthening,6 though there is evidence that using it as part of physical therapy program leads to good clinical outcomes that can be maintained after PT is completed.7,8 Immobilization is not indicated, but kinesiotaping may help although evidence is limited at this time. Unfortunately, chronic pain remains in up to 78% of patients despite rehabilitation, and rates of arthritis are higher.4 Surgery is usually only indicated as a last resort.5,9

Clinical Pearls

- PFS is a common condition which presents in up to 6% of adolescents

- History and physical is sufficient for making the clinical diagnosis

- NSAIDs may help with pain, but PT is the treatment of choice for strengthening of hips, trunk, and knee muscles to attempt to resolve the underlying issues

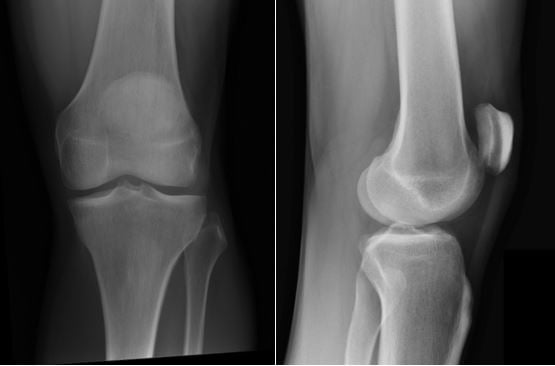

This is a normal knee X-ray as would be expected with PFS

Case courtesy of Dr Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 36689

Juvenile Osteochondritis Dessicans

Despite the nomenclature, the disease process is related to bone delamination and necrosis rather than cartilaginous injury or disease. Lateral aspect of the medial condyle of the femur is the most common site. This condition is not unique to athletes. Plain radiographs are indicated if the condition is suspected, as the lesion will be demonstrated as an area of lucency on x-ray. MRI may be obtained to assess for additional injury, as well as more detailed evaluation of the chondral lesion. However, this may be more useful in adults as compared to children and adolescents.9 The criteria for use in children have not yet been well defined, and adult criteria may not be applicable.10 Patients often present with anterior or medial knee pain. There may be small effusion on exam and often, but not always, tenderness to palpation of the femoral condyle. If a lesion is visualized, rest and activity restriction is the approach of choice and typically leads to spontaneous resolution in 8-12 weeks in children. The patient should be pain free, and x-ray should demonstrate healing. Spontaneous resolution is more common in children and adolescents than in adults. Knee immobilization can be indicated in severe cases as can surgical intervention for unstable versions.9 Stable lesions without adequate healing in 3-6 months warrant evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon for possible operative intervention.11

Clinical Pearls

- Rare condition usually diagnosed on x-ray

- Rest and activity restriction lead to resolution in the majority of patients

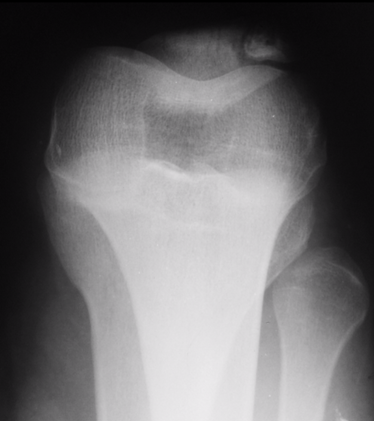

Case courtesy of Dr. Maulik S. Patel, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 10668

Patellar Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy of the patellar tendon is common, due to repetitive use and, in particular, high impact jumping. High body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, arch height, and quad and hamstring flexibility are risk factors.12 Pain is activity-related, and patients present with point-tenderness over the proximal patellar tendon, most notably during knee extension and which decreases with knee flexion.13 Assessment of weak or tight quads or hamstrings can be helpful to identify a possible etiology and identify areas to strengthen and stretch to reduce recurrence.

History and physical (as above) are the primary methods of diagnosis. If imaging is to be considered, US has been shown to be superior to MRI. Conservative treatment should be performed for up to six months. Eccentric squat therapy has been shown to improve symptoms and be appropriate for long-term improvement.14 During competitive periods, when short-term relief is key, isometric exercises may provide temporary improvement of pain. Use of a knee patellar strap, in addition to physical therapy, can also be helpful. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) and platelet rich plasma (PRP) have some data to support their use, but the data remain inconclusive. Dry needling has moderate data to support its use with little cost or downside.12 Surgical management is controversial and may or may not be associated with improvement in patients with chronic symptoms.

Clinical Pearls

- Clinical history is highly suggestive, and physical exam typically confirms diagnosis

- Six months of conservative treatment is indicated - consider recommendations of isometric exercises and a patellar strap

Quadriceps Tendinopathy

The most common anterior knee tendinopathy. Pain is typically at the insertion on the proximal patella. The approach is grossly similar to patellar tendinopathy described above. Pain and tenderness are common in the distal quadriceps, anterior knee, and proximal patella. Weakness of the quadriceps in extension may be present. Rest, ice, NSAIDs, and stretching are indicated. Temporary activity modification is usually required. Like patellar tendinopathy, a formal physical therapy treatment period can help improve these symptoms, working on both stretching and strengthening exercises.

Clinical Pearls

- Diagnosed by history and physical

- Rest, NSAIDs, and stretching are the mainstays, and PT may be helpful

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

This condition is an example of a juvenile apophysitis - inflammation of the area around the growth plate. It is a common overuse condition in children which presents as inflammation of the tibial tubercle apophysis with repetitive extension.15 The exact mechanism of this is unclear, though likely due to repetitive strain across the apophysis due to imbalance of the pull of the quadriceps muscle. The resulting inflammation presents with tenderness as well as pain, with forceful extension directly over the tibial tubercle. While traditionally taught as a condition of males, recent literature reveals no sex difference.16 History and clinical exam is sufficient for diagnosis, but x-rays can be obtained if it is part of a larger differential or if there is concern for a full avulsion. X-rays may demonstrate avulsion so should be obtained if this is considered.9 NSAIDs, rest, and ice are typically effective. Quadriceps and hamstring stretches should be incorporated into routine for all young athletes who have an open physis. Use of a patellar strap can also help decrease pain in some patients. The condition is generally self-limited with resolution after closure of the physis. Conservative management is successful in >90% of patients but operative management is indicated in some patients.16 Prominent tubercle can become permanent and can be a cosmetic concern. Arthroscopy can be performed to intervene on particularly resistant cases.15

Clinical Pearls

- Common condition of young athletes

- >90% respond to NSAIDs, rest, ice, and activity modification

Case courtesy of Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org From the case rID: 7511

Sinding-Larsson-Johansson Disease

This eponymous condition is another example of a juvenile apophysitis, pathophysiologically similar to Osgood-Schlatter. It occurs from the overuse of the inferior growth plate of the patella, resulting in inflammation and calcification. Excess stress from muscle pull over the apophysis during growth is associated with this condition. Patients present with inferior patellar pain with flexion when the patella is force loaded, such as running or jumping. There is often associated swelling and limitations on activity and/or performance. Plain radiographs can be helpful to differentiate bipartite patella from patellar fracture.17 US has been shown to be effective in identifying the condition. There are no long-term sequelae, and participation can be continued as tolerated. Pain may be persistent and may respond to NSAIDs. Similar to other apophysitis, rest in addition to stretching and strengthening can help improve symptoms. In some patients, prolonged rest is the best treatment.17 Steroid injections should not be performed.9

Clinical Pearls

- Less common but similar to Osgood-Schlatter

- US may help diagnose

- Activity as tolerated as there are no long-term sequelae

Case courtesy of Dr. Alan Jossimar Zavala Vargas, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 80636

Knee Bursitis

Bursae are fluid filled sacs that cushion large joints. Inflammation is most commonly due to chronic microtrauma but can also be due to acute injury, infection, or inflammatory arthritis. There are four bursae in the knee, and any one can be affected, leading to pain.12 Prepatellar bursitis is the most common and has a strong association with compression, especially due to kneeling. Swelling may be sufficient to limit range of motion, and effusion may be apparent grossly or on US.18 If there is concern regarding the etiology, laboratory workup can be helpful to rule out signs of infection.12 Fluid aspiration can also be helpful in identifying crystal or infectious inflammation, although this is rarely indicated. Chronic bursitis can be enduring despite NSAIDs, rest, and ice. Range of motion exercises and stretching should be performed, as well. Corticosteroid injection can be effective at relieving symptoms but is not without risks, particularly for superficial bursae.

Clinical Pearls

- Consider prepatellar bursitis in any patient with repeated kneeling and knee pain

- Can endure despite optimal conservative treatment. Steroid injection may help but is not without risks

Synovial Plica

A benign embryologic remnant, this condition has a prevalence of up to 50%. It commonly presents as chronic pain with intermittent “locking” or “catching” of the joint in adolescents and athletes. It most commonly is associated with flexion-extension movements, but why some people develop significant symptoms when the prevalence is so high in the general population remains unclear. MRI, while not necessary, typically reveals the remnant. Conservative management is indicated for most patients and consists of analgesics, NSAIDs, and PT. Efficacy varies widely in the literature, with reports as low as 40% and as high as 87%. Operative management to resect the structure is indicated for individuals with recalcitrant pain.

Clinical Pearls

- Extremely common finding that idiosyncratically causes pain and knee problems

- Response to conservative treatment is varied

This is an MRI diagnosis and is best appreciated with the full set of images

Case courtesy of Dr. Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 41239

Bipartite or Multipartite Patella

The patella typically arises from a single center of ossification. In some cases, it arises from two or more centers with connection of these segments by fibrous segment of tissue. Incidence is 90% male, and it is typically unilateral.9 Presentation is typically characterized by localized pain and swelling. X-ray is diagnostic, showing incomplete ossification. Most cases of bi- or multipartite patella are found incidentally.19 Rest of activity for a prolonged period and use of NSAIDS is indicated to manage conservative, and many patients have relief in three-four weeks. If necessary, orthopedic surgery may be necessary in some patients, but evidence on the optimal approach is lacking, and there are at least seven approaches found in the literature.

Clinical Pearls

- Most cases are found incidentally and typically respond well to conservative management

- Despite traditional teachings, this condition tends to be unilateral

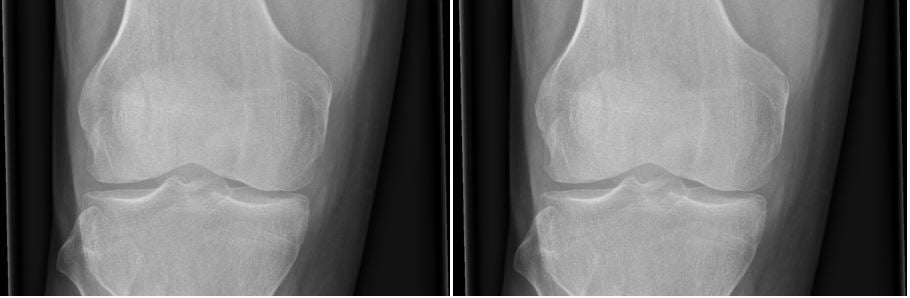

This is a subtle bipartite patella with lateral abnormality

Case courtesy of Dr. Sumit Verma, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 74103

Case courtesy of Dr. Aditya Shetty, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 27156

Summary

Anterior knee pain is a common presenting symptom with a broad differential. We present a broad overview of the differential diagnoses which must be considered with a patient presenting for AKP. History and physical are the most important factors in making the diagnosis. Imaging can be helpful in further characterization but is not usually necessary. The mainstay of treatment is rest, NSAIDs, and PT, but surgical intervention may be necessary in some cases.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s presentation is overall reassuring against fracture or surgical pathology. The presence of anterior knee pain in an adolescent runner, worse with prolonged flexion (the “theatre sign”), is highly suggestive of PFS. He is referred to PT and has significant improvement in symptoms after strengthening of the hip and knee.

References

- D'Ambrosi R, Meena A, Raj A, et al. Anterior knee pain: state of the art. Sports Med Open. Jul 30 2022;8(1):98. doi:10.1186/s40798-022-00488-x

- Lipman R, John RM. A review of knee pain in adolescent females. Nurse Pract. Jul 15 2015;40(7):28-36; quiz 36-7. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000466496.11555.ec

- Rice DA, McNair PJ, Lewis GN, et al. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: the effects of experimental knee joint effusion on motor cortex excitability. Arthritis Res Ther. Dec 10 2014;16(6):502. doi:10.1186/s13075-014-0502-4

- Kasitinon D, Li WX, Wang EXS, et al. Physical examination and patellofemoral pain syndrome: an updated review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. Dec 2021;14(6):406-412. doi:10.1007/s12178-021-09730-7

- Gaitonde DY, Ericksen A, Robbins RC. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician. Jan 15 2019;99(2):88-94.

- Na Y, Han C, Shi Y, et al. Is isolated hip strengthening or traditional knee-based strengthening more effective in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome? a systematic review with meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. Jul 2021;9(7):23259671211017503. doi:10.1177/23259671211017503

- Ferber R, Bolgla L, Earl-Boehm JE, et al. Strengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Athl Train. Apr 2015;50(4):366-77. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.70

- Khayambashi K, Fallah A, Movahedi A, et al. Posterolateral hip muscle strengthening versus quadriceps strengthening for patellofemoral pain: a comparative control trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. May 2014;95(5):900-7. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.022

- Patel DR, Villalobos A. Evaluation and management of knee pain in young athletes: overuse injuries of the knee. Transl Pediatr. Jul 2017;6(3):190-198. doi:10.21037/tp.2017.04.05

- Uppstrom TJ, Gausden EB, Green DW. Classification and assessment of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans knee lesions. Curr Opin Pediatr. Feb 2016;28(1):60-7. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000308

- Kocher MS, Tucker R, Ganley TJ, et al. Management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current concepts review. Am J Sports Med. Jul 2006;34(7):1181-91. doi:10.1177/0363546506290127

- Kuwabara A, Fredericson M. Narrative: review of anterior knee pain differential diagnosis (other than patellofemoral pain). Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. Jun 2021;14(3):232-238. doi:10.1007/s12178-021-09704-9

- Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R. Patellar tendinopathy: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. Dec 2016;24(12):e184-e192. doi:10.5435/jaaos-d-15-00703

- Catapano M, Babu AN, Tenforde AS, et al. Knee extensor mechanism tendinopathy: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Curr Sports Med Rep. Jun 1 2022;21(6):205-212. doi:10.1249/jsr.0000000000000967

- Circi E, Atalay Y, Beyzadeoglu T. Treatment of Osgood-Schlatter disease: review of the literature. Musculoskelet Surg. Dec 2017;101(3):195-200. doi:10.1007/s12306-017-0479-7

- Ladenhauf HN, Seitlinger G, Green DW. Osgood-Schlatter disease: a 2020 update of a common knee condition in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. Feb 2020;32(1):107-112. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000842

- Valentino M, Quiligotti C, Ruggirello M. Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome: A case report. J Ultrasound. Jun 2012;15(2):127-9. doi:10.1016/j.jus.2012.03.001

- Basha MAA, Eldib DB, Aly SA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in the assessment of anterior knee pain. Insights Imaging. Oct 1 2020;11(1):107. doi:10.1186/s13244-020-00914-2

- Soini V, Raitio A, Virkki E, et al. Treatment of congenital bipartite patella in pediatric population - a systematic review of the published studies. Acta Orthop Belg. Mar 2022;88(1):87-93. doi:10.52628/88.1.11