Soft Tissue Ultrasound

Brian D. Euerle, MD, FACEP

I. Introduction and Indications

- Many patients come to the emergency department with complaints related to the soft tissues, such as infection, injury, and abnormal masses.

- Traditionally, computed tomography and magnetic resonance have been used when imaging studies are needed in these patients; however, ultrasound is generally more readily available and in some instances is the preferred imaging study.1

- The most common use of bedside ultrasound in patients with soft-tissue abnormalities is in the evaluation of infections, including cellulitis, abscess, and necrotizing fasciitis. Other soft-tissue indications include the evaluation of cysts and lymph nodes. Ultrasound is also used to locate foreign bodies.

- Although the majority of abscesses are treated with incision and drainage, in certain cases, usually because of cosmesis, treatment with needle aspiration and antibiotics becomes an option. Ozseker and colleagues found that ultrasound-guided aspiration and irrigation of breast abscesses was preferred to surgical drainage for abscesses with a diameter less than 3 cm.2 Ultrasound provides dynamic real-time guidance for needle aspiration, increasing the likelihood of success.

II. Anatomy

- The structures that are imaged in soft-tissue bedside ultrasound are primarily the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle.

- The skin consists of two layers: the superficial epidermis and the deeper, thicker dermis.

- The subcutaneous tissue, located beneath the dermis, consists of connective tissue septa and fat lobules.3

- Fascia, a deeper structure, is a dense, fibrous membrane.4

- Muscle consists of long fibers grouped together into fascicles. Various layers of connective tissue surround the individual muscle fibers, fascicles, and entire muscles.

III. Scanning Technique, Normal Findings, and Common Variants

Equipment

- Selection of the appropriate transducer is an important aspect of soft-tissue bedside ultrasonography. Because most structures to be imaged are relatively superficial, a high-frequency (7–12 MHz) linear transducer is most useful and provides a good balance between imaging depth and resolution.

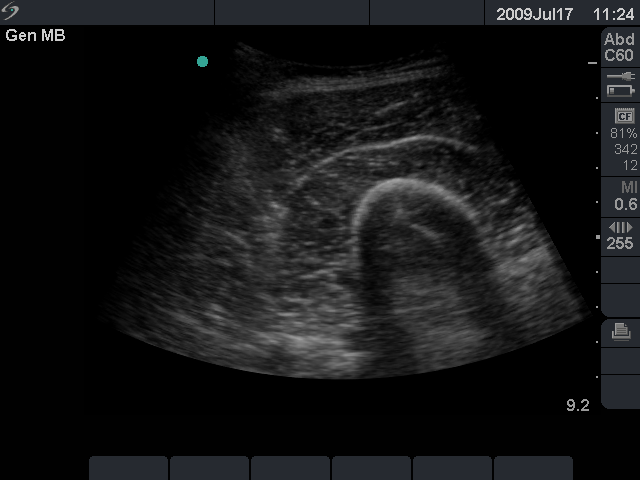

- On occasion, deeper structures need to be visualized; in these cases, a lower-frequency transducer is required. If a lower-frequency linear transducer is not available, then a curvilinear transducer may be used (Fig. 1).

- Figure 1. To image deep structures such as the thigh muscles, as shown here, a low-frequency curvilinear transducer may be used.

Scanning Technique

- The sonographer’s grip on the transducer is especially important in soft-tissue ultrasound because fine, controlled movements are often required. The transducer can be stabilized by resting part of the hand, such as the small finger or ulnar aspect, against the patient’s body.5

- In many cases, it is helpful to begin scanning a short distance away from the area of interest to gain an appreciation of the appearance of the normal, uninvolved anatomy. Then the transducer can be slid toward the area of interest.

- Images should be obtained in both longitudinal and transverse planes, which will provide the most information and allow accurate localization.6

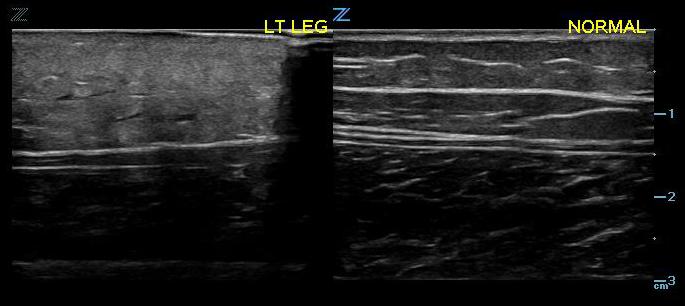

- It may be helpful to view the contralateral side of the patient’s body to obtain information about the normal appearance of structures.6

Normal Findings

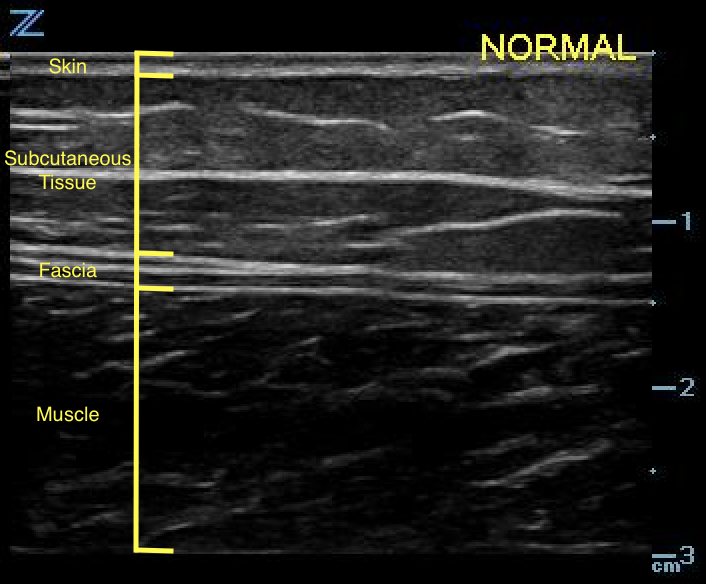

- With the equipment typically used for bedside ultrasonography, the epidermis and dermis cannot be differentiated. They appear together as a thin, hyperechoic layer.3

- The subcutaneous layer appears hypoechoic on ultrasound, with two components: hypoechoic fat interspersed with hyperechoic linear echoes running mostly parallel to the skin, which represent connective tissue septa (Fig. 2).3

- Veins and nerves can be visualized within the subcutaneous layer.

- Figure 2. Normal skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia

- Fascia appears as a linear hyperechoic layer. Its thickness will vary depending on the location.4

- Muscle fascicles can be visualized as hypoechoic cylindrical structures, with hyperechoic connective tissue (perimysium) surrounding them (Videos 1 and 2).4

- A characteristic feature of muscle is that its appearance on ultrasound changes with contraction; when contracted, it appears thicker and more echoic on short-axis planes.7

Video 1. Longitudinal image of muscle

Video 2. Transverse image of muscle - Lymph nodes are hypoechoic and generally oval.8

Video 3. Lymph node

IV. Pathology

Cellulitis

- Cellulitis is the pathologic condition very frequently encountered during soft-tissue bedside ultrasonography. The ultrasound appearance of cellulitis varies depending on its stage and severity.

- The initial appearance may be generalized swelling and increased echogenicity of the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 5).9,10

- Figure 3. Early cellulitis (left) compared with normal (right)

- As cellulitis progresses and the amount of subcutaneous fluid increases, hyperechoic fat lobules become separated by hypoechoic/anechoic fluid-filled areas. This later stage of cellulitis is most typical and has been described as having a cobblestone appearance (Fig. 6).9

Video 4. Cobblestone appearance of advanced cellulitis - The appearance of fluid-filled interlobar septae is not specific for cellulitis but, rather, is indicative of generalized subcutaneous edema, which can result from conditions such as congestive heart failure.9

- Color and power Doppler are advanced ultrasound modalities that can help determine whether the inflammation characteristic of cellulitis is present. However, their use in the emergency department is beyond the skills of some emergency practitioners, who will instead rely on the physical examination for clinical correlation.

- Tayal and colleagues studied the use of bedside ultrasound in emergency department patients with signs of cutaneous soft-tissue infection but no signs of obvious abscess.11 The use of ultrasound changed the management of a significant percentage of the study group. By routinely utilizing ultrasound in the evaluation of these patients, the physicians were able to avoid unnecessary drainage procedures as well as detect occult abscesses. Other researchers have since found similar results.12-16

Necrotizing Fasciitis

- Necrotizing fasciitis is an uncommon, severe, life-threatening infection that involves the subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle.

- On ultrasound, it appears as thickened distorted fascia with an adjacent hypoechoic fluid collection, along with swelling of the subcutaneous tissue and muscle.9

- Small foci of gas appear as bright echogenic areas with posterior acoustic shadowing.3,9,17

- Morrison et al17 used ultrasound to evaluate emergency department patients with Fournier’s gangrene and found subcutaneous scrotal gas in all cases. The authors concluded that bedside ultrasound was very useful

Video 5. Fournier’s gangrene with gas evident surrounding the testicle

Cysts

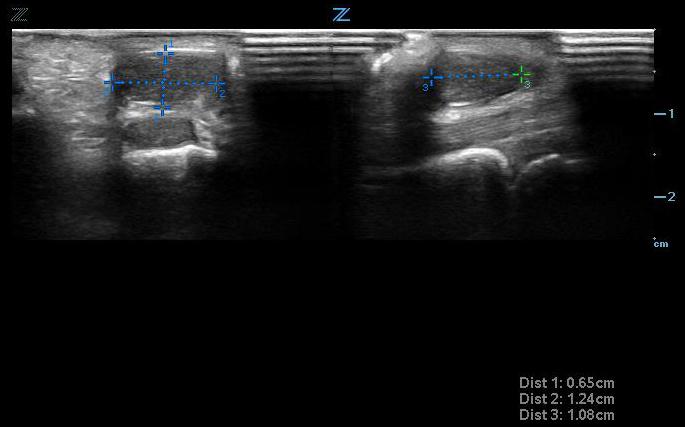

- Ultrasound can help differentiate solid from cystic masses. Ganglion cysts are a common cystic mass that arises from tendon sheaths and joints (Fig. 7). They are filled with a gelatinous material. On ultrasound, they appear anechoic and can cause posterior acoustic enhancement.18 It might be possible to trace the cyst to its origin from the tendon sheath or joint space.

- Figure 4. Small ganglion cyst seen transversely (left) and longitudinally (right) above tendon

Video 6. Small ganglion cyst above tendon

Lymph Nodes

- Normal and reactive lymph nodes have the same ultrasound appearance: they are hypoechoic, with an echogenic hilus, and are generally oval (See Video 3).8

- Malignant lymph nodes are usually hypoechoic, without an echogenic hilus, and round. This distinction is beyond the skill and experience of most emergency physicians, who should not attempt to differentiate these two entities. However, they can use ultrasound to identify a mass as a probable lymph node.

Foreign Bodies

- Ultrasound is useful in the evaluation of wounds and other soft tissue that might contain foreign bodies. It is especially useful in the search for radiolucent foreign bodies, which are difficult or impossible to detect by plain radiography or computed tomography. Please see the Foreign Body Chapter (LINK TO THAT CHAPTER) for more information.

V. Pearls and Pitfalls

- Holding the transducer so that part of the examiner’s hand rests on the patient provides stability and allows the fine, controlled movements that are necessary.

- Start scanning on nearby, uninvolved body areas to gain an appreciation of normal anatomy. Scanning the contralateral corresponding body part can also help in this regard.

- Small echogenic foci of gas are highly suspicious for necrotizing fasciitis.

The author thanks Linda J. Kesselring, MS, ELS, for her assistance with preparing the manuscript.

VI. References

- Nazarian LN. The top 10 reasons musculoskeletal sonography is an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(6):1621-6.

- Ozseker B, Ozcan UA, Rasa K, et al. Treatment of breast abscesses with ultrasound-guided aspiration and irrigation in the emergency setting. Emerg Radiol. 2008;15(2):105-8.

- Valle M, Zamorini MP. Skin and subcutaneous tissue. In: Bianchi S, Martiloni C, eds. Ultrasound of the Musculoskeletal System. Springer: Berlin; 2007:19-43.

- O’Neill J. Introduction to musculoskeletal ultrasound. In: O’Neill J, ed. Musculoskeletal Ultrasound: Anatomy and Technique. Springer: New York; 2008:3-17.

- Jacobson JA. Fundamentals of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound. Saunders: Philadelphia; 2007.

- Kaplan PA, Matamoros A Jr, Anderson JC. Sonography of the musculoskeletal system. Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155(2):237-45.

- Zamorini MP, Valle M. Muscle and tendon. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, eds. Ultrasound of the Musculoskeletal System. Springer: Berlin; 2007:45-96.

- Ahuja AT, Ying M. Sonographic evaluation of cervical lymph nodes. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1691-9.

- Chau CL, Griffith JF. Musculoskeletal infections: ultrasound appearances. Clin Radiol. 2005;60(2):149-59.

- Chao HC, Lin SJ, Huang YC, Lin TY. Sonographic evaluation of cellulitis in children. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19(11):743-9.

- Tayal VS, Hasan N, Norton HJ, Tomaszewski CA. The effect of soft-tissue ultrasound on the management of cellulitis in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):384-8.

- Sivitz AB, Lam SH, Ramirez-Schrempp D, et al. Effect of bedside ultrasound on management of pediatric soft-tissue infection. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(5):637-43.

- Berger T, Garrido F, Green J, et al. Bedside ultrasound performed by novices for the detection of abscess in ED patients with soft tissue infections. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(8):1569-73.

- Adams CM, Neuman MI, Levy JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pediatric soft tissue infection. J Pediatr. 2016;169:122-7.

- Gaspari RJ, Sanseverino A. Ultrasound-guided drainage for pediatric soft tissue abscesses decreases clinical failure rates compared to drainage without ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(1):131-6.

- Iverson K, Haritos D, Thomas R. The effect of bedside ultrasound on diagnosis and management of soft tissue infections in a pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(8):1347-51.

- Morrison D, Blaivas M, Lyon M. Emergency diagnosis of Fournier’s gangrene with bedside ultrasound. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(4):544-7.

- Hwang S, Adler RS. Sonographic evaluation of the musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Ultrasound Q. 2005;21(4):259-70.