November 29, 2021

Pericardiocentesis

Michael Mirza, MD

Christopher Bryczkowski, MD, FACEP

I. Introduction and Indications

- The pericardial space usually contains 15-50 ml of fluid, which serves as lubricant between the visceral and parietal layers of the pericardium.

- Several systemic conditions can cause an increased amount of fluid in this space. Blood can also collect in this space following trauma.

- Clinical manifestations are highly dependent on the amount and rate of accumulation of this fluid or blood.

- The worst outcome is ventricular collapse causing a precipitous drop in cardiac output, hypotension and possible cardiac arrest.

- Using bedside echocardiography allows the emergency physician to rapidly evaluate the pericardium and identify the presence of a pericardial effusion.

- Identification of a pericardial effusion causing collapse of the right ventricle is diagnostic of pericardial tamponade and mandates immediate pericardiocentesis.1-3

- Presence of a pericardial effusion in shock and/or cardiac arrest may indicate the need for emergent pericardiocentesis.4

Indications

- Cardiac tamponade or cardiac arrest in the setting of pericardial effusion large enough to be a contributing factor.

II. Anatomy

See cardiac chapter for anatomy details.

III. Scanning Technique and Sonographic Findings

Commonly attempted ultrasound views for this procedure are the subxiphoid (SX) and parasternal long axis (PSLA) view. However, the optimal position of the probe depends on multiple factors including patient position and body habitus, and oftentimes good results can be achieved with an apical or apical/PSLA approach.

(See also cardiac chapter for more details.)

- Subxiphoid

- The probe is placed transversely at the left costal margin at the level of the subxiphoid process with the ultrasound beam aimed at the patient’s left shoulder.

- Probe indicator should be to the patient’s right.

- The structures closest to the probe will appear on top of the screen display with the liver being a landmark.

- The liver borders the right ventricle of the heart.

- A pericardial effusion will appear as an anechoic area surrounding the heart.

- Video 1. Subxiphoid view of the heart with pericardial effusion causing tamponade

- Parasternal

- The transducer is placed in the left parasternal area between the 2nd and 4th intercostal spaces.

- Probe indicator should be facing the patient’s left hip.

- Provides good images of left atrium, mitral valve, left ventricle, proximal ascending aorta.

- Look for anechoic area surrounding the heart.

There are several advantages to performing this procedure with the transducer on the anterior chest adjacent to the needle as opposed to the transducer positioned in the subxiphoid position distant from the needle entry point:

- In the subxiphoid view, the heart and hence the effusion you are trying to drain is located perpendicular (out of a direct in-line plane) to the ultrasound beam making it difficult to visualize the needle tip without dynamic movement of the probe to confirm that what is visualized is actually the tip (and not a 2D cut of any other portion of the needle). This is analogous to the long axis vs short axis techniques used for vascular access.

- Placing the transducer on the chest wall in the parasternal long axis aligns the beam in the same plane as the structure of interest with close proximity to the needle giving you excellent visualization.

- In addition to being closer to the skin surface and hence the effusion, the parasternal approach steers clear of other vital structures such as the liver and lung. In addition, being able to visualize the needle tip confidently in a PSLA approach prevents inadvertent penetration of heart chambers.5-7

- Video 2. PSLA view of the heart with pericardial effusion causing tamponade

- Apical

- The transducer is placed near the patient’s point of maximal impulse under the left breast or inframammary fold.

- Probe indicator should be facing the patient’s right hip.

- Look for anechoic area surrounding the heart.

- Advantages and approach are similar to parasternal long approach above.

- Video 3. Apical view of the heart with pericardial effusion causing tamponade

III. Pathology

Procedure Technique

- The chest wall is prepped and draped in standard surgical fashion.

- The ideal site of skin puncture is where the fluid accumulation is closest to the skin surface (chest wall). A curvilinear or phased array transducer covered in a sterile sheath with frequency ranging from 2.5 – 3.5 mHz is placed on the left anterior chest wall in the parasternal long axis.

- Look for the anechoic area on the top of the screen above the right ventricle.

- The distance from the transducer to the center of the effusion can be measured using the measuring tool on the machine.

- Video 4. Measuring distance to pericardial effusion and heart

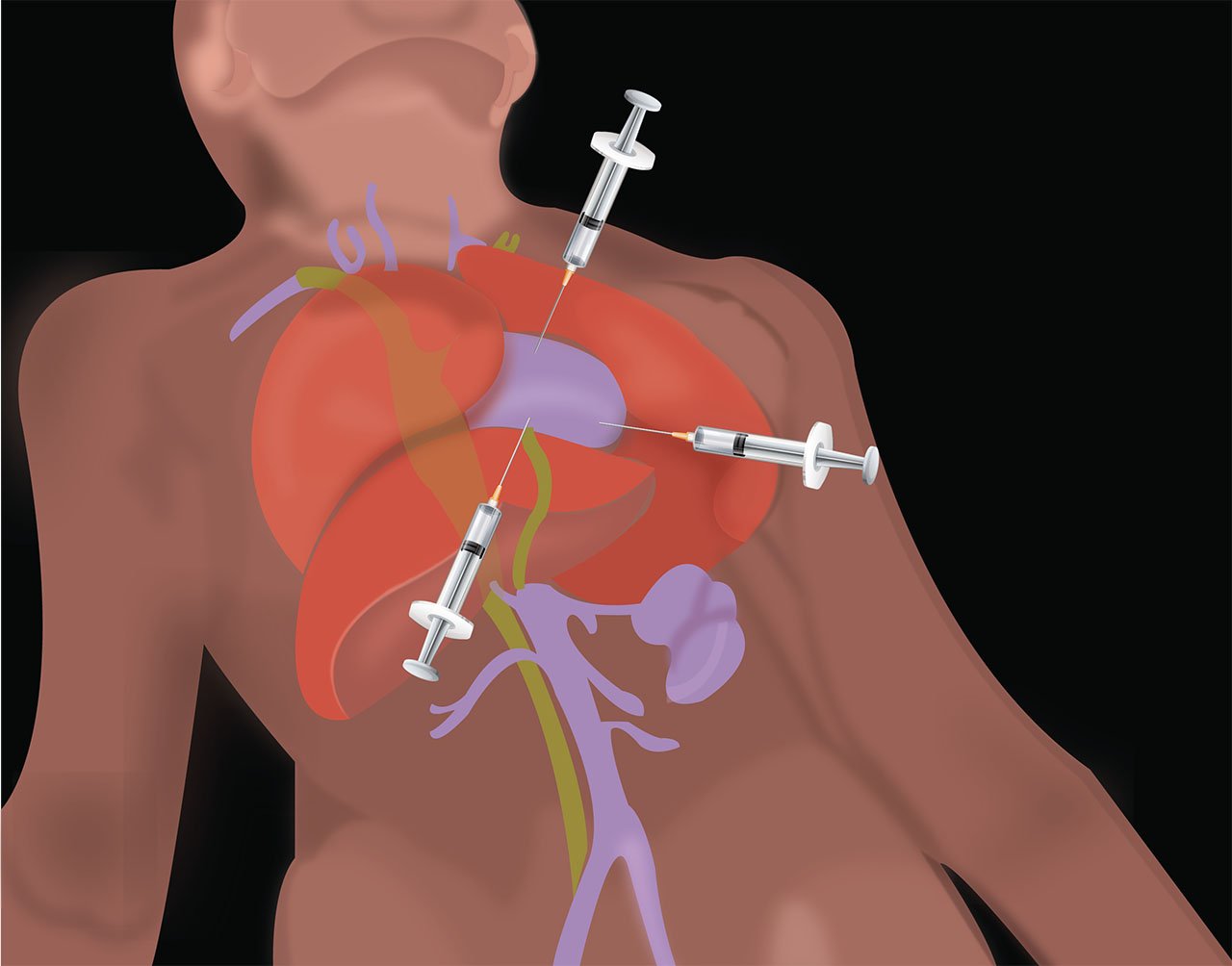

- A 16–18 gauge needle attached to a syringe is inserted in the same plane as the transducer in the PSLA or apical view through the chest wall and into the pericardium.

- It is key to keep the needle in line with the transducer when utilizing a PSLA or apical view and to be oriented as to where the echogenic needle tip will first be seen.

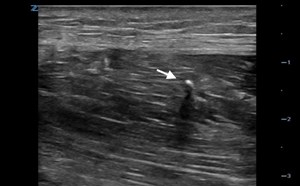

- Figure 1. Position of the ultrasound probe for parasternal ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis

- Illustration 1. Schematic view of pericardiocentesis

- It is key to keep the needle in line with the transducer when utilizing a PSLA or apical view and to be oriented as to where the echogenic needle tip will first be seen.

- If using a SX view, the needle will be placed perpendicular to the probe.

- For placement confirmation, it is also recommended to use the ‘activated saline technique.’

- Here the position of the needle is confirmed by injecting agitated saline through the needle, creating a ‘bubble appearance’ within the pericardial effusion and confirming placement within the fluid-filled pericardial sac.

- Video 5. Pericardiocentesis (visualizing the needle entrance through the chest wall and seen entering in the middle of the screen) (Courtesy of Dr. Srikar Adhikari)

- Video 6. Agitated saline being injected into the pericardial effusion

- Video 7. Agitated saline filling entire pericardial space in setting of pericardial effusion

- Here the position of the needle is confirmed by injecting agitated saline through the needle, creating a ‘bubble appearance’ within the pericardial effusion and confirming placement within the fluid-filled pericardial sac.

IV. Pearls and Pitfalls

- Confusing the epicardial fat pad with pericardial effusion. Remember the fat pad is an anterior structure and effusions are usually circumferential.

- Overlooking large pericardial effusions because they are clotted. Remember that clotted blood appears less anechoic than fresh blood, or can even be isoechoic to surrounding structures.

- Video 4. Pericardial Clot (Courtesy of Dr. Srikar Adhikari)

- Normal pericardium will appear as a single, brightly echogenic stripe next to the myocardium.

- Add a flexible sheath to permit repeated drainage.

V. References

- Singh S, Wann S, Schuchard GH, et al. Right ventricular and right atrial collapse in patients with cardiac tamponade: a combined echocardiographic and hemodynamic study. 1984;70: 966–71.

- Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28; 113(12):1622-32.

- Jung HO. Pericardial effusion and pericardiocentesis: role of echocardiography. Korean Circulation J. 2012;42(11):725-34.

- Tayal VS, Kline JA. Emergency echocardiography to detect pericardial effusion in patients in PEA and near-PEA states. Resuscitation. 2003;59(3):315-8.

- Tsang TS, Enriques-Sarano M, Freeman WK, et al. Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis. Clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002. 77(5):429-36.

- Dewitz A, Jones R, Resnick J. et al. Additional Ultrasound-Guided Procedures. In: Ma O.J, Mateer JR, eds. Emergency Ultrasound. 3rd edition, 645-708. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2014.

- Tibbles CD, Porcaro W. Procedural applications of ultrasound. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(3):797-815.