June 10, 2020

Gallbladder

I. Introduction and Indications

- Gallbladder (GB) disease is very common, affecting 8% of men and 17% of women.1,2

- Biliary tract disease is the 3rd most common cause of acute abdominal pain presenting to the ED.3-5

- It is important to differentiate biliary causes of pain from other common causes such as gastritis, renal disease and idiopathic abdominal pain.

- The primary focus of biliary point-of-care ultrasound is examining for the presence of gallstones.

- Other aspects of the study can include examining for sonographic Murphy’s sign, gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid and common bile duct dilation.

- Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice in patients with suspected gallbladder pathology.

- Indications include upper abdominal pain, right flank pain, jaundice and appropriate patients presenting with sepsis or septic shock.

- When EM physicians perform bedside ultrasound, the sensitivity and specificity for determining the presence of gallstones was over 86% and 88% respectively.6-8 The general sensitivity and specificity for ultrasound diagnosing cholecystitis is 94% and 84% respectively.9

- Difficulty identifying the CBD can cause angst among novice sonographers. However, with no abnormal findings on bedside ultrasound of the GB and no abnormal liver/pancreas labs, isolated CBD dilation is exceedingly uncommon (<1%).10,11

II. Anatomy

- The gallbladder is an elongated pear-shared organ that lies on the inferior surface of the liver. The liver occupies a prominent region of the right upper abdomen.

- The body of the gallbladder gradually tapers to the neck which empties into the cystic duct.

- After a short distance, the cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct to become the common bile duct (CBD). The CBD typically courses with the hepatic artery and the portal vein.

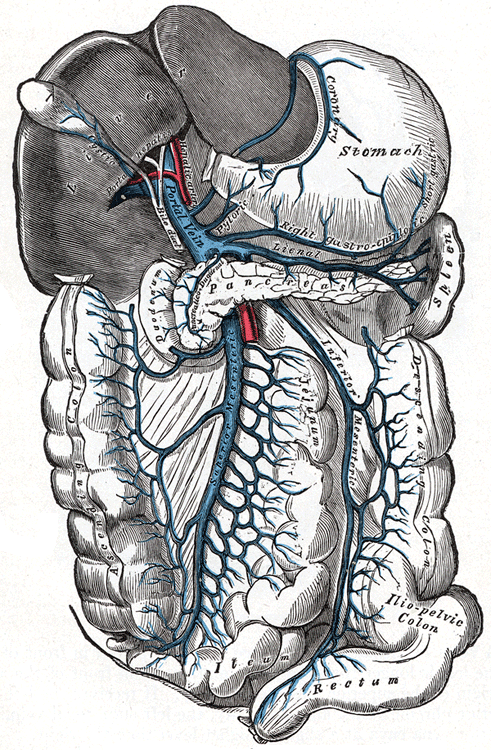

- Image 1: Hepatobiliary Anatomy: Notice the CBD runs parallel to the portal vein and the hepatic artery in a sagittal orientation.

- These three structures, known as the portal triad, can be used as landmarks to help identify each other – the portal vein and hepatic artery having flow on color Doppler and the CBD having no flow. There are many anatomic variations and imaging of the CBD can be very challenging for the beginner sonographer.

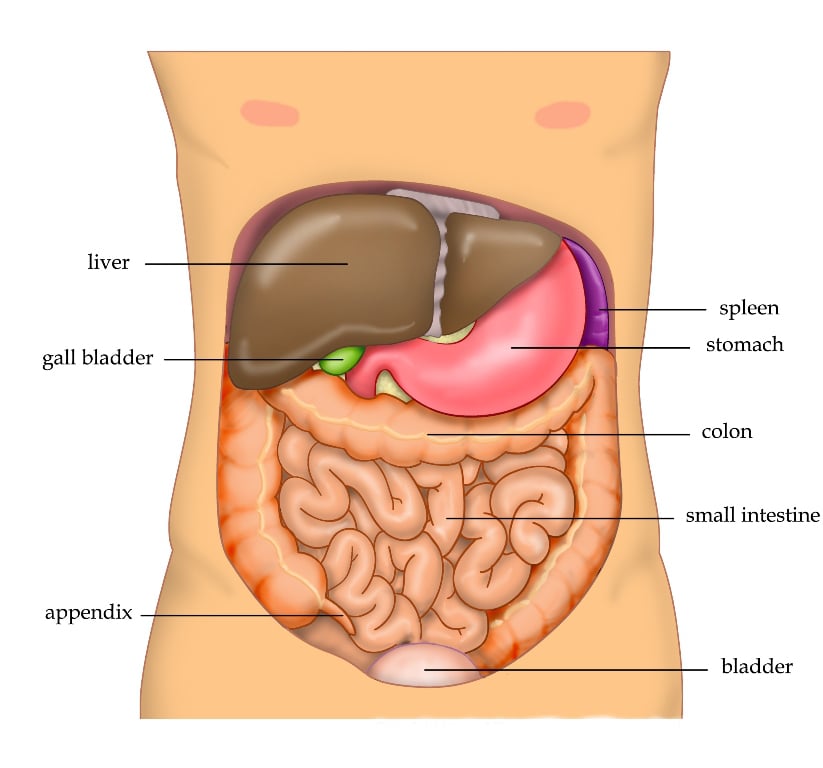

- Image 2: Abdominal Anatomy: Notice the close relationship of the stomach and intestines, all of which can have air that obstructs imaging of the gallbladder.

III. Scanning technique, normal findings, and common variants

- Scanning technique: In general, the curvilinear probe should be used to perform this exam. Lower frequency can be used for obese patients to help with sound penetration.

- The phased array probe may be useful if the gallbladder can only be imaged using an intercostal window.

- Gallbladder:

- Subcostal Sweep Approach - Place the probe in sagittal (longitudinal) orientation with the probe-indicator oriented toward the patient’s head and instruct the patient to take a deep breath. Sweep the probe inferiorly and laterally along the right subcostal margin. (Video 1)

- Video 1. Subcostal Sweep with sound

- X-Minus 7 Approach - Find the xiphoid process and move laterally to the right 7 centimeters. Place the probe perpendicular to the skin between the ribs (usually in an axial/horizontal plane). In most cases, the gallbladder will be found posterior to the liver immediately beneath the probe. (Video 2)

- Video 2. X-Minus 7 with sound

- Use color Doppler if in doubt of gallbladder which is a cystic structure and has no flow. (Video 3)

- Video 3. Gallbladder with no flow

- After identifying the gallbladder, VERY slowly rotate/sweep to create the best long-axis view. (Videos 4 & 5)

- Video 4. Probe rotation and fanning with sound

- Video 5. Long-axis of gallbladder

- Fan through the entire gallbladder with careful attention to the neck of the GB where solitary stones can hide.

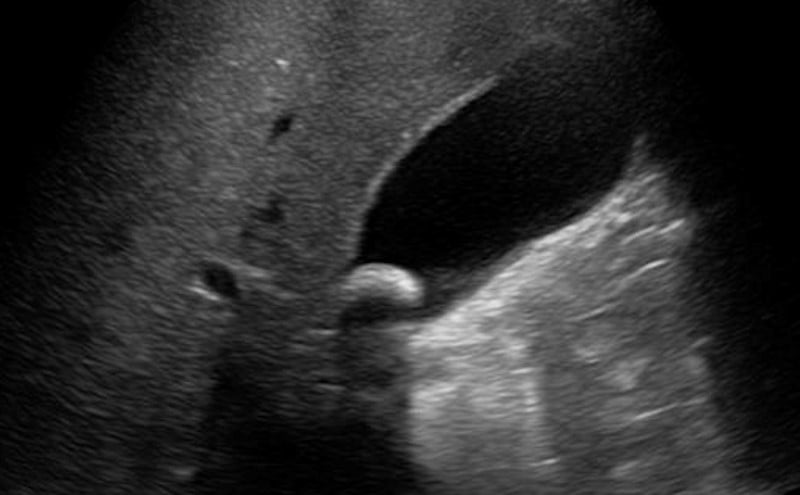

- Figure 1: Solitary stone in gallbladder neck

- Next, rotate the probe 90 degrees to obtain a transverse view of the gallbladder. Again, slowly fan through the gallbladder to access for stones.

- In addition to stones, measuring wall thickness can be useful. This should always be done in short-axis. (Video 6)

- Video 6. Measuring wall thickness

- A positive sonographic Murphy sign is when maximal pain is elicited when pressing directly over the sonographically visualized GB. (Video 7)

- Video 7. Sonographic Murphy with sound

- Subcostal Sweep Approach - Place the probe in sagittal (longitudinal) orientation with the probe-indicator oriented toward the patient’s head and instruct the patient to take a deep breath. Sweep the probe inferiorly and laterally along the right subcostal margin. (Video 1)

- Common Bile Duct:

- Most easily found by following the GB neck towards the prominent portal vein. The CBD and hepatic artery are generally smaller than and anterior to the portal vein – the hepatic artery with flow on color Doppler and the CBD without flow. (Video 8)

- Video 8. Measuring the normal CBD with sound

- If seen in true cross-section, the combination will form the “Mickey Mouse sign” – a face and two ears. (Video 9: CBD with Mickey Mouse Sign with sound)

- Video 9. CBD with Mickey Mouse Sign with sound

- Rotating counter-clockwise allows visualization of both the CBD and portal vein in long axis

- Most easily found by following the GB neck towards the prominent portal vein. The CBD and hepatic artery are generally smaller than and anterior to the portal vein – the hepatic artery with flow on color Doppler and the CBD without flow. (Video 8)

IV. Normal Findings

- The normal GB is pear-shaped, hypoechoic with a hyperechoic wall.

- Gallbladder long axis: Fan through the entirety of the gallbladder to identify any pathology (See Video 5 above: Long-axis of the gallbladder).

- Gallbladder short axis (See Video 6 above: Gallbladder short-axis): Rotate the probe 90 degrees. The GB will appear round. Again, fan through the entire GB.

- GB wall thickness: Measure the anterior wall thickness in short axis and try to keep the probe perpendicular to the GB to avoid false measurements. (Video 10)

- Video 10. Measuring GB wall thickness

- CBD: Measure inner wall to inner wall (See Video 8 above)

- Normal GB wall thickness ≤ 3 mm, Normal CBD diameter ≤ 6 mm (normal varies with age and a person older than 60 can have 1mm per decade of life – eg, 90 years old can have a normal CBD diameter of 9mm); Post-cholecystectomy can have a very large diameter and this is often normal.

- Common variants: There are many variations of gallbladder and CBD position and course. This can make ultrasound of the GB and CBD challenging.

V. Pathology

- Gallstones are the primary pathology of interest and can be any size from large to tiny (even sludge) and from solitary to numerous (Video 11: Sludge; Video 12: Small stones/sludge; Video 13: Many stones; Video 14: Large solitary stone).

- Video 11. Sludge

- Video 12. Small stones/sludge

- Video 13. Many stones

- Video 14. Large solitary stone

- In the appropriate patient, finding gallstones can help focus the differential and diagnosis or lead to comprehensive radiology performed ultrasound.

- If a gallstone is visualized, the patient should be rolled to the left lateral decubitus position assess for mobility of the stone.

- GB completely filled with stones gives the “Wall-Echo-Shadow (WES) Sign.” This can be challenging to differentiate from gas-filled bowel. (Video 15)

- Video 15. Wall-Echo-Shadow Sign

- Sonographic Murphy's sign (See Video 7 above: Sonographic Murphy’s sign): Positive when maximal tenderness is directly over the gallbladder. The sensitivity of the sonographic Murphy’s sign is reported from 75-86% with a positive predictive value of 92% when combined with the finding of gallstones.12-14

- Abnormal GB Wall Thickness: Causes include cholecystitis as well as ascites, CHF, post-prandial state and others. (Video 16)

- Video 16. Severe Gallbladder Wall Thickening

- Pericholecystic fluid: Usually found in segments around a thickened GB wall. (Video 17 )

- Video 17. Pericholecystic Fluid

- Dilated CBD which can be caused by an obstructing stone, pancreatic mass or by previous cholecystectomy. Remember that color Doppler can help identify the CBD and differentiate it from the vascular structures. (Videos 18 & 19)

- Video 18. Dilated Common Bile Duct

- Video 19. Dilated Common Bile Duct

VI. Pearls and pitfalls

- Tips on image acquisition and interpretation

- Always have the patient’s arms at their sides and the knees bent to relax the abdominal wall musculature.

- Having the patient take and hold a deep breath can bring the liver and GB below the costal margin.

- When having the patient hold a breath, the examiner can also hold their breath to help remember that this can be uncomfortable.

- Having the patient either more upright in bed or lying on the left side can likewise help shift the liver and gallbladder, making them easier to image.

- Common mistakes

- Stomach and bowel (especially the duodenum) can mimic a thick-walled, stone-filled gallbladder.

- A distended appearing gallbladder can be normal in a patient who hasn’t eaten recently.

- A contracted gallbladder with thickened wall can be normal in a patient who has recently eaten. It will appear small and not distended, sometimes challenging to find.

- Gallbladder folds and polyps can mimic stones and can give false-positive findings.

VII. References

- Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, et al. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. 1999;117(3):632-9.

- Go V, Everhart JE. Gallstones. In: Digestive diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and impact US Department of Health and Human Service. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 1994. NIH Publication no. 94-1447.

- Powers RD, Guertler AT. Abdominal pain in the ED: stability and change over 20 years. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13(3):301-3.

- Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. 2002;122(5):1500-11.

- Diehl AK. Epidemiology and natural history of gallstone disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20(1):1-19.

- Testa A, Lauritano EC, Giannuzzi R, et al. The role of emergency ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute non-traumatic epigastric pain. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:401-9.

- Schlager D, Lazzareschi G, Whitten D, et al. A prospective study of ultrasonography in the ED by emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:185-9

- Kendall JK, Shimp RJ. Performance and interpretation of focused right upper quadrant ultrasound by emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2001;21(1):7-13.

- Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(22):2573-81.

- Becker BA, Chin E, Mervis E, et al. Emergency biliary sonography: utility of common bile duct measurement in the diagnosis of cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2014 Jan;46(1):54-60.

- Lahham S, Becker BA, Gari A, et al. Utility of common bile duct measurement in emergency department point of care ultrasound: A prospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(6):962-6.

- Ralls PW, Colletti PM, Lapin SA, et al. Real-time sonography in suspected acute cholecystitis. Prospective evaluation of primary and secondary signs. Radiology. 1985;155(3):767-71.

- Bree RL. Further observations on the usefulness of the sonographic Murphy sign in the evaluation of suspected acute cholecystitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23(3):169-72.

- Kendall JL, Shimp RJ. Performance and interpretation of focused right upper quadrant ultrasound by emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2001;21(1):7-13.