Minimally Invasive Procedures for Headaches

Background

Headache is one of the most common reasons for presentation to an emergency department (ED). In the United States, headache accounts for 3% of all visits.1 Headaches can either be primary or secondary. Primary headaches include migraine, tension or cluster headaches. Secondary headaches are caused by a separate underlying process (ie, vascular, infectious or traumatic) and can be potentially life-threatening. The first step in managing headache in the ED is to identify patients who are at a high risk for a secondary cause. Some high-risk features to consider include trauma, altered mental status, neurologic changes, associated infectious symptoms, no prior history of headaches or a history of other conditions (ie, malignancy, autoimmune diseases).1 In addition to ruling out life-threatening pathology, we must also provide pain relief to our patients. There are many effective oral and parental first-line treatments for primary headaches, such as NSAIDs, anti-emetics, anti-epileptics, triptans, antipsychotics and muscle relaxants. Some of these first line medications can have significant side effects, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, serotonin syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, vascular occlusion and rebound headaches. This article focuses on alternative, minimally invasive therapies for headaches. Although there are mixed studies regarding some of these therapies, they may offer efficient and rapid relief with minimal side effects.

Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block

The sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) is a parasympathetic ganglion found in the posterior to the middle turbinate and is few millimeters deep to the lateral nasal mucosa.2 The SPG block has been used to treat primary headaches, as the activation of the sphenopalatine ganglion leads to parasympathetic-mediated symptoms, such as nasal congestion, lacrimation, conjunctival injection found in primary headache patients.3 Activation of the ganglion also leads to parasympathetic-mediated release of neuropeptides leading to vasodilation intra- and extracranial arteries related to migraine headaches, making the SPG a target for treatment.3

There have been a few studies evaluating the efficacy of the SPG block in the ED with mixed results. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials looking at intranasal lidocaine for acute migraine was published by Chi et al. in PLOS One. The analysis revealed that the population receiving intranasal lidocaine had a statically significant lower pain intensity level at 5 and 15 mins, higher success rate (42.6% vs. 10.3%) and had a lower need for rescue medicine (39.2% vs 77.2%).4 The study also noted that there was no beneficial effect to using intranasal lidocaine when an antiemetic was used.4

Some side effects noted with intra-nasal SPG block include epistaxis, infection if nasal mucosa is penetrated, numbness in throat (recommend patients avoid eating or drinking to decrease risk of choking until this resolves) and nausea.

Trans-nasal Approach

There are various approaches to achieving a SPG block such as trans-nasal, transoral, and infrazygomatic. The most practical method for emergency department use is the trans-nasal approach which has minimal risk of side effects, non-invasive and is quick to administer.

- Obtain 10 cm cotton-tipped applicator and local anesthetic (1-4% lidocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine)

- Soak the cotton-tip in local anesthetic

- Place patient’s head in sniffing position, insert the soaked cotton into naris, slowly and steadily advance along the superior border of the middle turbinate until the posterior wall of nasopharynx

- Leave the applicator in place for 10-20 minutes

- Reassess

Or

- Obtain atomization device, 5 cc syringe, 2% lidocaine

- Apply 2cc of lidocaine to bilateral nares

- Hold pressure for 30 seconds

- Reassess patient in 10-15 minutes

Occipital Nerve Block

This nerve block is indicated for patients with migraine headaches or cervicogenic headache, which presents as pain with occipital, upper cervical spine, forehead and retrobulbar areas with associated ipsilateral eye lacrimation and conjunctival injection.2 The pain can be described by patients as electric shock-like or stabbing sensation. The goal is to block the greater occipital nerve which is made up of sensory fibers from C2 spinal nerve and provides cutaneous innervation to the majority of the posterior scalp.5 The neurons of the greater occipital nerve converge with the trigeminal nerve fibers, which are implicated in causing migraines and occipital neuralgia symptoms.2 This nerve block can provide longer-lasting relief, can be safely performed in the ED setting, and works just as well, if not better, than other treatments.6

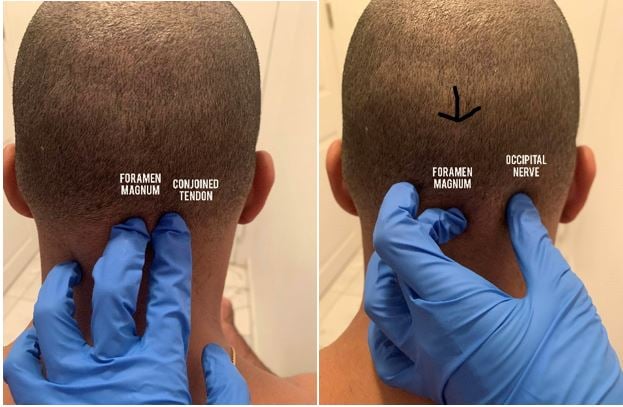

Three Landmark Technique

- Obtain 1.5 inch 25 or 27-gaugle needle, 3cc syringe, 18-gauge needle to draw up solution, sterile gloves, alcohol swabs, 1% to 2% lidocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine.

- Position patient:

- sitting with the head flexed forward and the head resting on the hands

- lying prone on an examination table with pillow or rolled blanket underneath chest to allow for head and neck flexion

- Identify the foramen magnum, the conjoined tendon, and the occipital nerve groove of the skull just lateral to the tendon with your hand.

4. Clean the area with alcohol swab (shaving the area is not necessary).

5. Enter at a 45- degree angle form patient’s skin and aim the needle superiorly and medially and advance until contact is made with bony skull.

6. Aspirate, inject 2 cc of local anesthetic.

7. Reassess patient

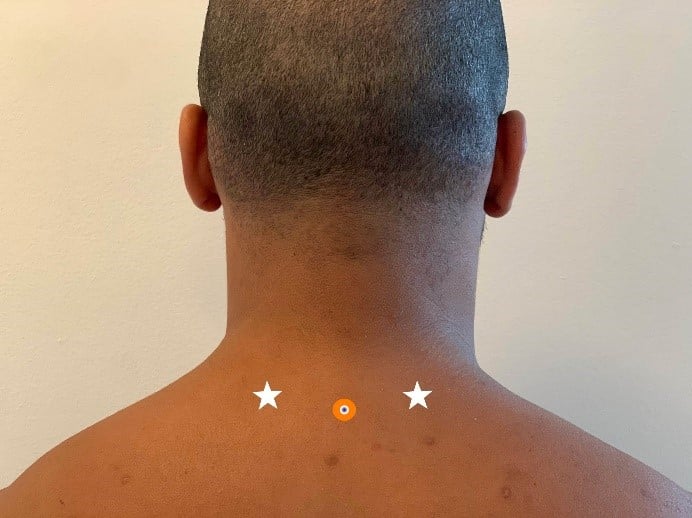

Paraspinal Cervical Injection

Paraspinal cervical injection was studied by Mellick, et al, in 2006 for use in the ED. The technique is listed below. Mellick, et al, published a review of 417 patients receiving paraspinal muscle injections lateral to C6 or C7. The review found that 65% of patients had complete relief of headache and found partial relief in 20.4% of patients.7 The relief for patients was rapid within 5-10 mins. The side effects noted included muscle soreness at injection site, brightening of vision, and transient weakness of posterior neck muscles.

Technique

- Position the patient in either 1) seated position with head flexed forward or 2) prone.

- Obtain 5 cc syringe, 0.5% bupivacaine, 18-gauge needle to draw up solution, sterile gloves, 1.5 inch 25-gauge needle, alcohol or ChloraPrep.

- Sanitize over the lower cervical and upper thoracic dorsal spine.

- Insert needle 1-1.5 inches into paraspinal muscle at an angle parallel to floor/exam table.

- Inject 1.5 cc (per injection site) into the paraspinous muscles bilateral to the C6 or C7 spinous process (2-3 cm from the spinous process).

References

- Koyfman A, Long B. Headache. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; . http://accessemergencymedicine.mhmedical.com.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/content.aspx?bookid=2353§ionid=189593946.

- Narouze S. Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block. In: Diwan S, Staats PS. eds. Atlas of Pain Medicine Procedures New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015. http://accessanesthesiology.mhmedical.com.ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/content.aspx?bookid=1158§ionid=64176604.

- Khan S, Schoenen J, Ashina M. Sphenopalatine ganglion neuromodulation in migraine: what is the rationale? Cephalalgia. 2014;34(5):382-391.

- Chi PW, Hsieh KY, Chen KY, et al. Intranasal lidocaine for acute migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0224285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224285

- Ashkenazi A, Levin M. Greater occipital nerve block for migraine and other headaches: is it useful? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11(3):231-5.

- Voigt C, Murphy M. Occipital nerve blocks in the treatment of headaches: safety and efficacy. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(1):115-129.

- Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1‐year retrospective review of 417 patients. 2006 Oct;46(9):1441-1449. PMID: 17040341

Martha L. Castro, MD

PGY-3, NYU/Bellevue Emergency Medicine