Snap, Crackle, and Pop! Acute papillary muscle rupture identified with POCUS

Critical Care Subcommittee

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) from a nursing facility in acute respiratory distress. He had a recent inferior wall myocardial infarction (MI) with an unsuccessful PCI of the right coronary artery. The patient was placed on CPAP by the prehospital providers for hypoxia with an SpO2 of 76%.

On arrival, he was found to be in extremis and was taken into the resuscitation bay where his SpO2 was 85% on CPAP. His lungs had diffuse crackles, he was using accessory muscles with paradoxical abdominal breathing, and had bounding pulses in all four extremities. Despite maximal medical and non-invasive ventilatory support the patient developed worsening respiratory distress. He was ultimately intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. A portable chest x-ray confirmed the endotracheal tube was in the proper position and he was diagnosed with cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema. Post-intubation, the patient remained difficult to oxygenate and he continued to decompensate becoming hypotensive.

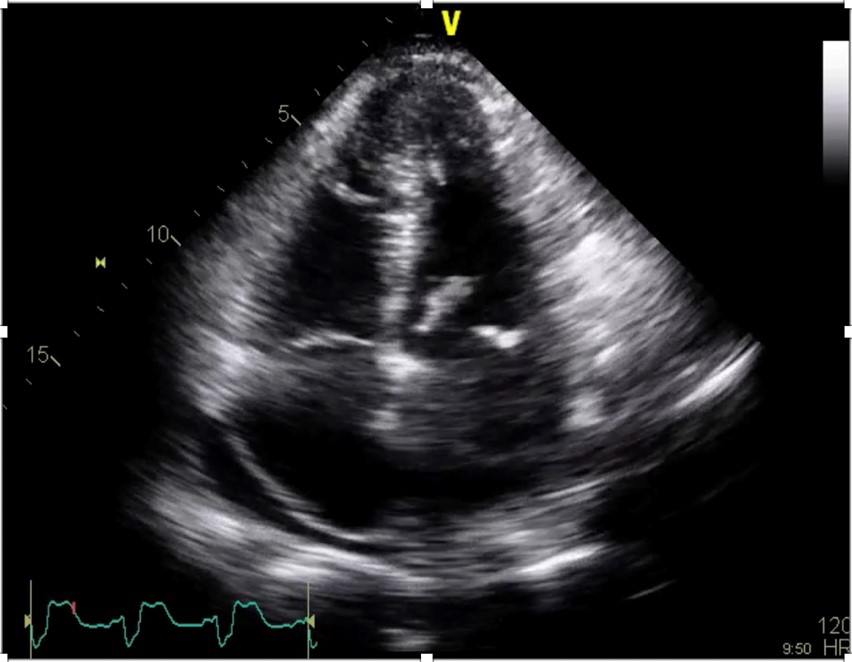

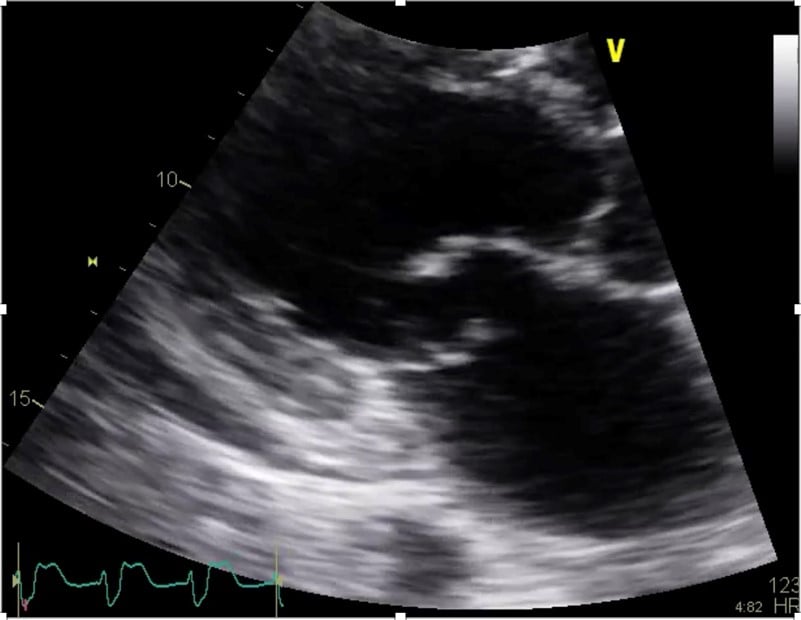

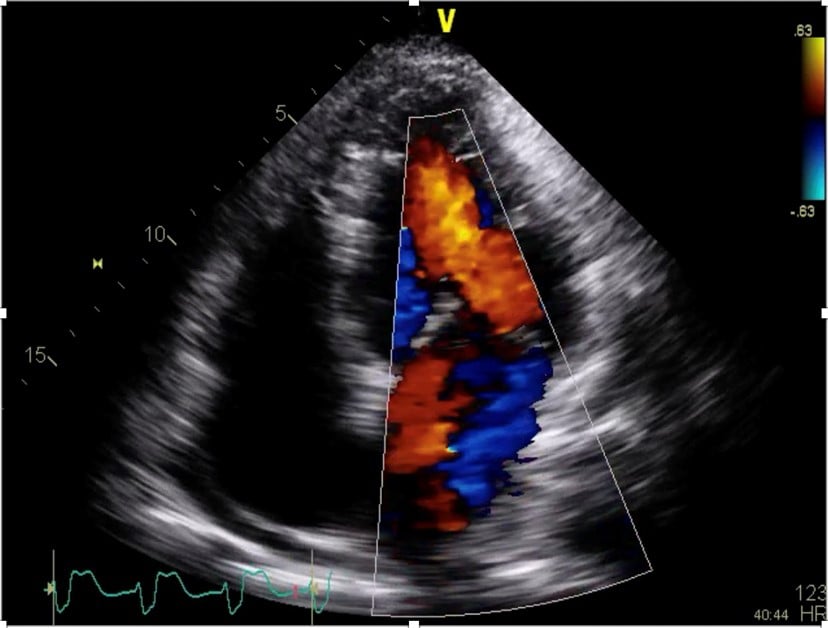

A point-of-care ultrasound was performed to help differentiate the cause of hypoxia and hypotension. The findings were consistent with the sequela of the patients recent RCA occlusion which demonstrated a newly identified flail posterior mitral valve leaflet and severe mitral regurgitation (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Subsequently, the patient was taken emergently to the cath lab for placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP). The balloon pump was adjusted to maximize the diastolic augmentation and minimize pre-systolic LV afterload to optimize the patient’s cardiac function.1 Once he was stabilized, the patient was taken to the operating room for a mitral valve replacement. After a prolonged hospital course, the patient survived to discharge and was sent to a skilled nursing facility for cardiac rehabilitation.

Education

Papillary muscle rupture can occur within 24 hours of an acute inferior or posterior myocardial infarction. It is the cause of 1-3% of cardiogenic shock in patients post-MI.2 Surgical repair is listed as a Class I recommendation by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). With surgical intervention the patient still has a mortality rate of 19% to 53%, and without surgical intervention the mortality rate goes up to 80%.3-6 Aggressive supportive treatment includes temporary afterload reduction to improve cardiac output while awaiting surgery. If the patient is already hypotensive, you may have to place the patient on a vasopressor, as well as an afterload reducer.7

Early recognition of papillary muscle rupture and knowledge of the options for aggressive supportive treatment and early surgical repair can make the difference between life and death. In this case, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) made the diagnosis which expedited the patients care and saved his life.

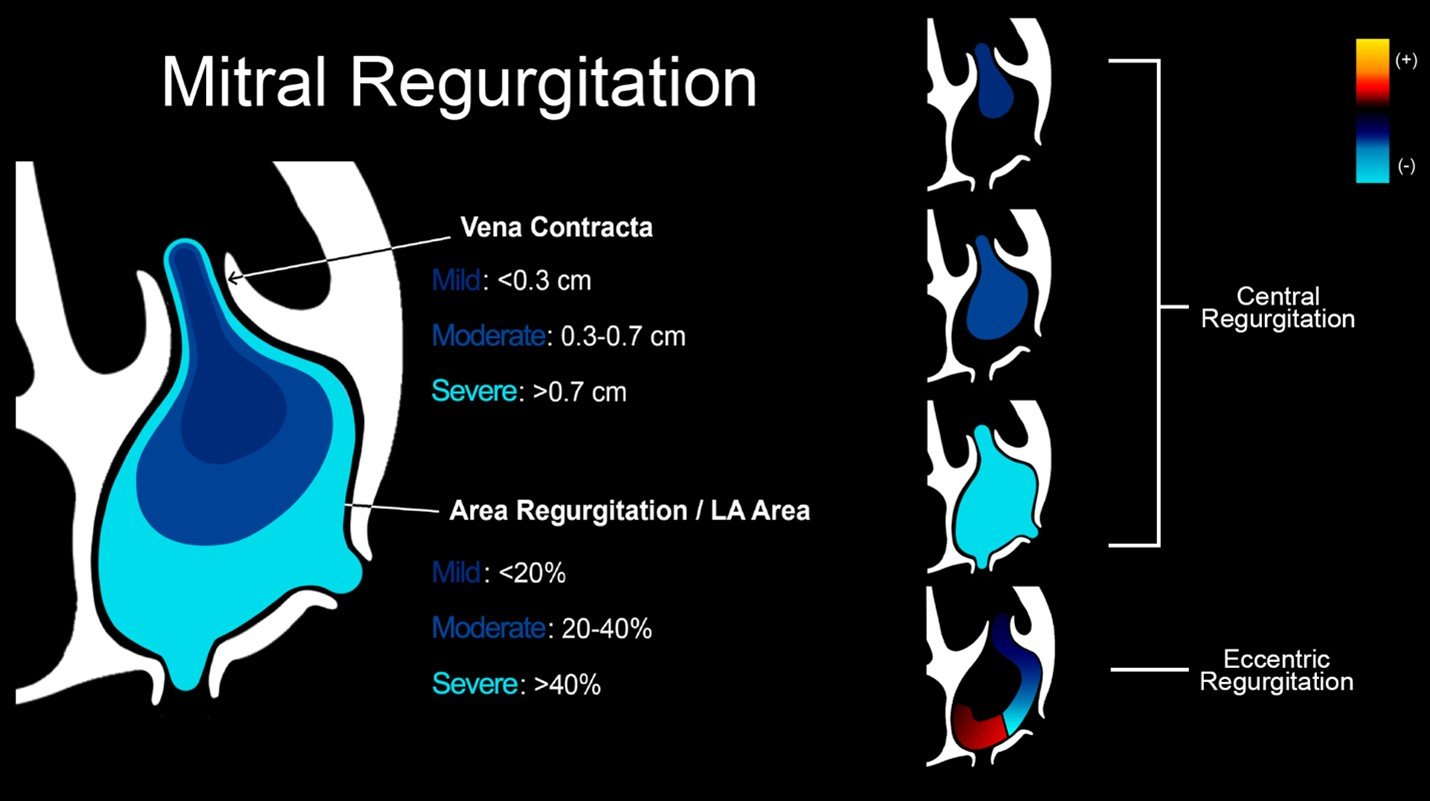

ACEP’s critical care ultrasound subcommittee has been working on advanced cardiac ultrasound educational cards to share with the community as a reference when performing critical care POCUS.

Figure 1. Apical 4 chamber view of a flail posterior mitral valve leaflet.

Figure 2. Close-up view of a flail posterior mitral valve leaflet and a small pericardial effusion in the parasternal long axis view

Figure 3. Apical 4 chamber view of a flail posterior mitral valve leaflet using color doppler demonstrating an eccentric mitral regurgitation.

Figure 4. Illustration of an advanced cardiac ultrasound educational card on mitral regurgitation.

References

- Khan TM, Siddiqui AH. Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump (IABP). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542233/

- Tcheng JE, Jackman JD, Nelson CL, et al. Outcome of patients sustaining acute ischemic mitral regurgitation during myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:18-24.

- Thompson CR, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, et al. Cardiogenic shock due to acute severe mitral regurgitation complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Should we use emergently revascularize occluded coronaries in cardiogenic shock? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3 suppl A):1104-9.

- DiSesa VJ, Cohn LH, Collins JJ, et al. Determinants of operative survival following combined mitral valve replacement and coronary revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 1982;34:482-9.

- Czer LS, Gray RJ, DeRobertis MA, et al. Mitral valve replacement: impact of coronary artery disease and determinants of prognosis after revascularization. Circulation. 1984;70(3 pt 2):I198–I207.

- Schroeter T, Lehmann S, Misfeld M, et al. Clinical outcome after mitral valve surgery due to ischemic papillary muscle rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:820-4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.10.050.

- Valle JA, Miyasaka RL, Carroll JD. Acute mitral regurgitation secondary to papillary muscle tear. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(6):e005050.

Lindsay Taylor, MD

Assistant Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University Health System

Zan Jafry, MD, FACEP

Emergency Ultrasound Systems Director