International Ultrasound: Small Bowel Obstruction Secondary to Ascariasis Infection: An Alarming Finding in the Remote Territory of Eastern Honduras

Background

Small bowel obstructions (SBO) are a common gastrointestinal condition which may require surgical intervention. It is estimated that over 300,000 laparotomies per year are performed in the United States alone for adhesion-related obstructions.1 Common risk factors for SBO in developed countries include prior abdominal or pelvic surgeries, hernias, intestinal inflammation, prior radiation therapy, or history of foreign body ingestion.1 However, in countries with limited resources, the differential diagnosis often differs from the more typical etiologies seen in the United States. With limited access to radiologic imaging, the use of portable ultrasound for diagnosing SBO becomes increasingly important in areas such as these.

Case Presentation

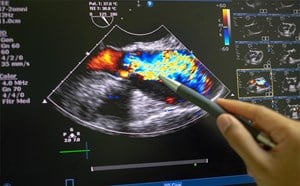

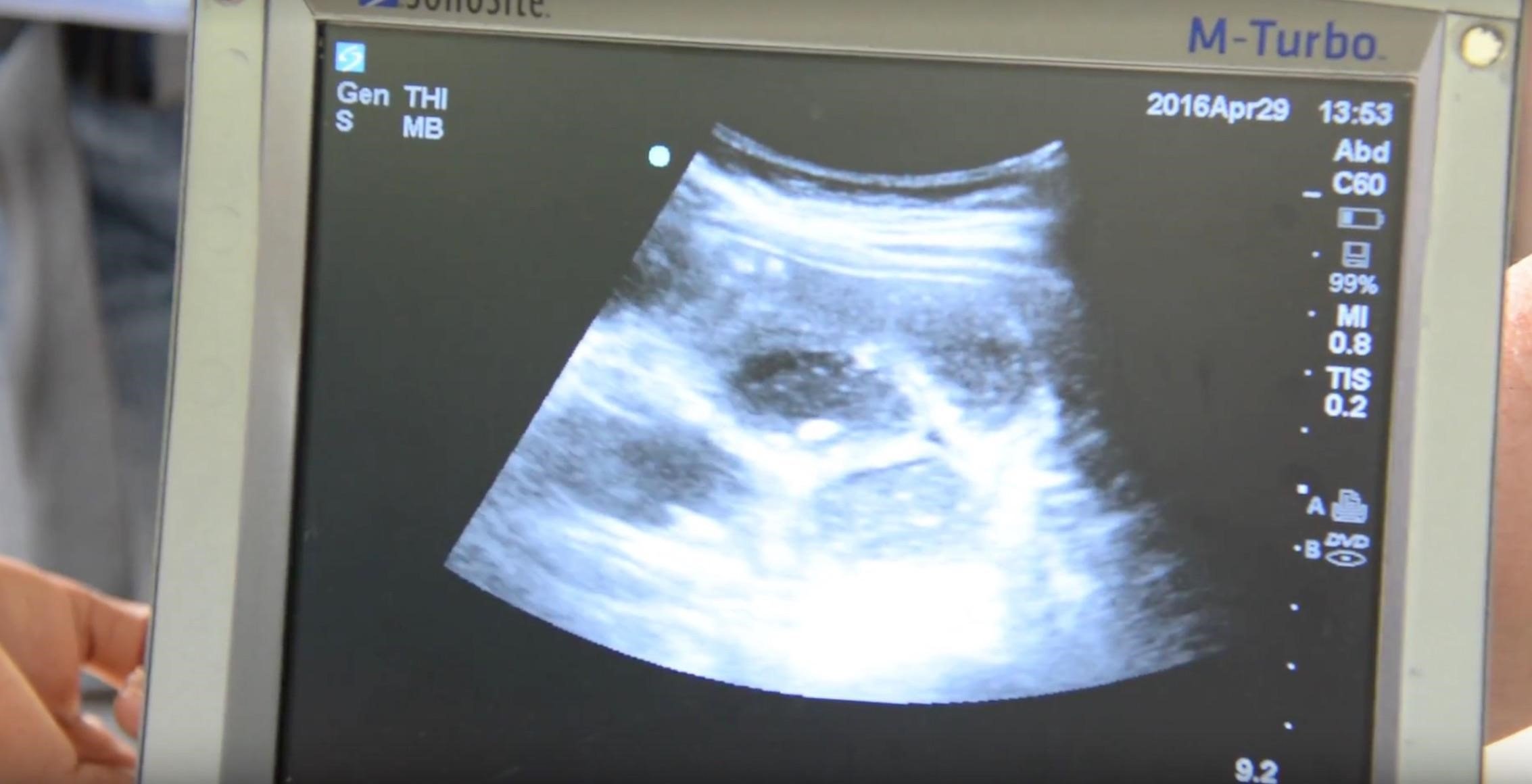

We present the case of a 15-year-old female patient with no known past medical history who presented to a transient medical clinic in the remote territory of La Moskitia, Honduras with a three-month history of poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, and worsening epigastric pain. She was initially diagnosed as gastritis at an external clinic. However, a point-of-care ultrasound examination was performed, and she was diagnosed with a small bowel obstruction (SBO) (Figure 1). During her visit, she had an episode of emesis, which demonstrated a large worm consistent with an Ascaris lumbricoides (Figure 2). The etiology of the SBO was suspected to be secondary to physical obstruction from the Ascariasis obstruction.

Figure 1. Portable ultrasound that was used to diagnose a small bowel obstruction.

Figure 2. A roundworm retrieved from the emesis of a female with a SBO secondary to ascariasis infection appears next to a Honduran lempira, roughly the same size as a dollar bill.

Discussion

Ascaris lumbricoides lives in the intestines of an infected host and transmits eggs through the feces of the host, most commonly through oral ingestion from contaminated water or subcutaneously from stepping on the feces of a human that has been infected.2 The eggs of the parasite first hatch in the intestines of the infected host and the larvae move into the bloodstream where it establishes residency in the lungs.3 After a process of maturing, the roundworms leave the lungs and travel into the trachea, where they are expectorated or swallowed into the esophagus. The worms that are ingested travel back into the intestines, where they continue to grow, mate, and produce additional eggs. An uninterrupted progression of this parasitic infection can lead to SBO as the roundworms reproduce in the intestines to a level that impedes the normal flow of digestive material through the gastrointestinal tract. If left untreated, the condition can lead to death by dehydration or intestinal perforation. Ascariasis infections can typically be treated by common antihelminthic drugs, such as albendazole, ivermectin, and mebendazole.4 In advanced cases causing SBO, surgical intervention requiring enterotomy or resection may be necessary if the complete obstruction does not improve within 24-48 hours.5

Ultrasonography has been shown to be a useful adjunct in the evaluation of patients with suspected SBO as it can be performed rapidly and with high accuracy, even when performed under minimal training.6,7 The diagnosis is made based upon a small intestinal diameter of greater than 2.5 cm with abnormal peristalsis.6 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that ultrasound was 92.4% sensitive and 96.6% specific with a positive likelihood ratio of 27.5 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.08.8 Therefore, ultrasound can be a valuable adjunct for making the diagnosis and is particularly valuable in areas where access to advanced imaging is limited. In this case, ultrasound was able to make the diagnosis and lead to transfer to an advanced healthcare facility, which may not have otherwise been possible.

References

- Bordeianou L, Yeh DD. Epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis of mechanical small bowel obstruction in adults. In W. Chen, MD, PhD (Ed.), 2017 Retrieved January 20, 2018, from here

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. The Lancet. 2006;367:1521-32.

- Dold C, Holland CV. Ascaris and ascariasis. Microbes and infection. 2011;13(7):632-7.

- Ortiz JJ, Chegne NL, Gargala G, et al. Comparative clinical studies of nitazoxanide, albendazole and praziquantel in the treatment of ascariasis, trichuriasis and hymenolepiasis in children from Peru. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002;96:193-6.

- Teneza Mora NC, Lavery EA, Chun HM. Partial small bowel obstruction in a traveler. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(2):256-8.

- Jang T, Schindler D, Kaji A. Bedside ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel obstruction in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(8):676-8.

- Taylor MR1, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Jun;20(6):528-44.

Gottlieb M, Peksa GD, Pandurangadu AV, et al. Utilization of ultrasound for the evaluation of small bowel obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(2):234-242.

Jett MacPherson, MS21

Saundra Jackson, MD, FACEP2

Wesley Wallace, MD3

1Marshall University, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine

2Emergency Resources Group, Jacksonville, FL

3University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Emergency Medicine