Double Defibrillation: Where’s That on the ACLS Algorithm?

Case Presentation

EMS calls ahead with notification of a 54-year-old male who collapsed while walking on a college campus. Bystander hands-only CPR was performed, and one shock was delivered by an automated external defibrillator (AED). The EMS crew arrives and states that the initial rhythm was ventricular fibrillation (VF). A total of three shocks, and two doses of epinephrine were given in route, all with on-going CPR. VF is noted on the hospital monitor, and a fifth shock is delivered. CPR is continued, and amiodarone is administered. On the next pulse check, VF is seen again, so another shock is delivered. Calcium gluconate is given, in addition to another dose of epinephrine, all while good-quality CPR is being continued. VF is seen yet again, and a seventh shock is administered. At this point, someone in the resuscitation team suggests performing double defibrillation (DD). ACLS, however, says nothing about it, let alone how to do it or if it even works. So now what?

Diagnosis

Refractory ventricular fibrillation (RVF)’s definition varies. One consistent description is persistent VF without response to three or more defibrillations.1-5 RVF depends on multiple variables: time in VF, body habitus (despite animal models showing inverse relationship with defibrillation), total defibrillator energy used, chronic lung disease, and use of antiarrhythmic agents.6,7

Management and Discussion

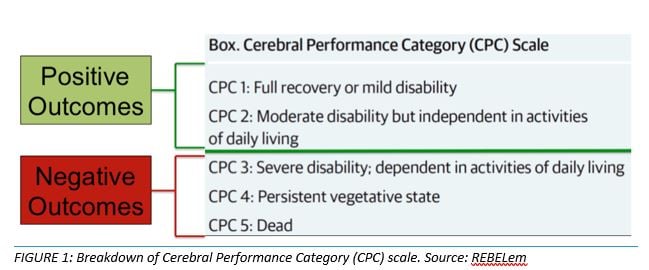

Multiple case reports have shown the effectiveness of a second defibrillator in terminating RVF.3-5,8,9. In a large literature review, DD terminated RVF in 77% of the 39 cases. More importantly, 11 of those patients who received DD were discharged with a Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score of 2 or less, indicating good neurologic outcomes. 2 (Figure 1)

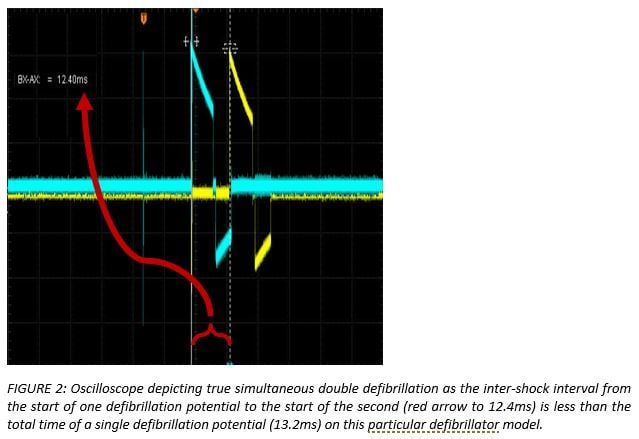

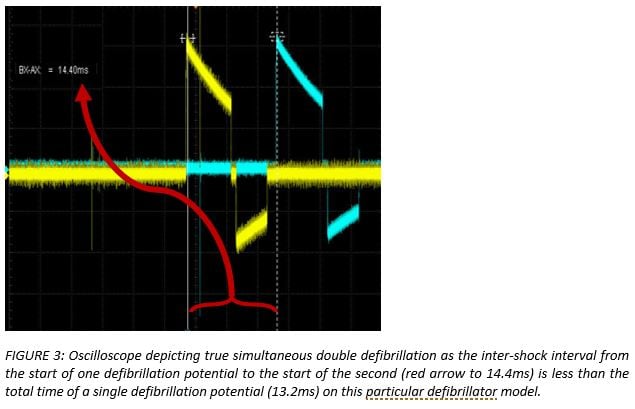

DD can either be simultaneous (Figure 2) or sequential (Figure 3), depending on the duration of the defibrillation potential and the intershock interval between the two defibrillator shocks.4,9-12 There is currently no evidence suggesting sequential or simultaneous is more effective. There are three main hypothesized theories as to why DD is effective:

- More Power Theory: Several studies have shown that higher energy has improved success on subsequent defibrillation.4,13-16 This is why DD is often termed “Double Simultaneous Defibrillation (DSiD)”. Lack of real-time measuring devices and subsequent delay in human response times makes it difficult to consistently perform true simultaneous defibrillation in the clinical setting. Furthermore, several studies have shown safety in patients receiving up to 720 Joules (J) of monophasic energy for conversion of RVF and atrial fibrillation.8,13,16-18

- Setting Up Theory: It is suggested that the first shock lowers the defibrillation threshold, thus increasing the second shock’s success in converting any remaining fibrillating myocytes.8,18 This is where DD gets its alternate name of “Double Sequential Defibrillation (DSD)”. It is also the more likely method of administration in clinical setting.

- Multiple Vector Theory: This proposed theory suggests that more pads increase the number of vectors that the electricity can use to reach the myocardium.8,18

Key Points When Performing DD

- If ventricular fibrillation is noted on the second pulse check, obtain a second defibrillator early so it is ready to use on the third pulse check, if needed.

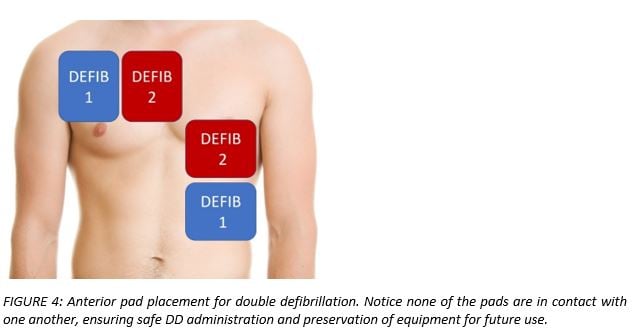

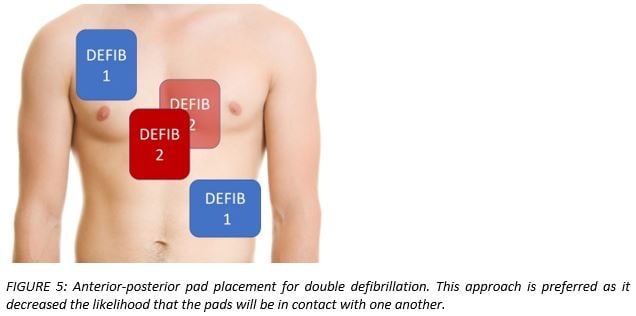

- Pad placement options:

- Anterior (Figure 4)

- Anterior-posterior (Figure 5)

- Defibrillator pads should NEVER be touching! The electrical discharge from one defibrillator may revert back into the second, causing both to no longer be functional!

- If attempting DSiD, having one provider push “shock” on both defibrillators decreases the chances for delay and optimizes the probability of simultaneous administration.

- If attempting DSD, having two providers each push “shock” on both defibrillators ensures a slightly delayed administration of the shocks in sequential fashion.

Case Resolution

The patient received a total of three DDs that resulted in ROSC after 61 total minutes of resuscitation. Hypothermia protocol was initiated, he was found to have a 100% occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery in the percutaneous catheter lab. He was extubated the next day and subsequently discharged without any neurologic deficits.9

Conclusion

While further research is needed to better understand DD, it is important to note that VF survival rates in out of hospital cardiac arrest can reach as high as 40-60% when combined with high quality CPR and early defibrillation.19-22 Double defibrillation, despite not in ACLS guidelines, serves as another tool during resuscitation and should be considered with other lifesaving interventions.

References

- Slovis CM, Wrenn KD. The technique of reversing ventricular fibrillation: improve the odds of success with this five-phase approach. J Crit Illn. 1994 Sep;9(9):873-89. PMID: 10147464

- Hajjar K, Berbari I, El Tawil C, et al. Dual defibrillation in patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;36(8):1474-9. PMID: 29730094

- Cabañas JG, Myers JB, Williams JG, et al. Double sequential external defibrillation in out-of-hospital refractory ventricular fibrillation: a report often cases. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015 Jan-Mar;19(1):126-30. PMID: 25243771

- Leacock BW. Double simultaneous defibrillators for refractory ventricular fibrillation. J Emerg Med. 2014 Apr;46(4):472-4. PMID: 24462025

- Cortez E, Krebs W, Davis J, et al. Use of double sequential external defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016 Nov;108:82-6. PMID: 27521470

- Sirna SJ, Ferguson DW, Charbonnier F, et al. Factors affecting transthoracic impedance during electrical cardioversion. Am J Cardiol. 1988 Nov 15;62(16):1048-52. PMID: 3189167

- Sirna SJ, Kieso RA, Fox-Eastham KJ, et al. Mechanisms responsible for decline in transthoracic impedance after DC shocks. Am J Physiol. 1989 Oct;257(4 Pt 2):H1180-3. PMID: 2801977

- Hoch DH, Batsford WP, Greenberg SM, et al. Double sequential external shocks for refractory ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Apr;23(5):1141-5. PMID: 8144780

- El Tawil C, Mrad S, Khishfe BF. Double sequential defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Dec;35(12):1985. PMID: 28978402

- Bell CR, Szulewski A, Brooks SC. Make it two: A case report of dual sequential external defibrillation. CJEM. 2018 Sep;20(5):792-7. PMID: 28587703

- Boehm KM, Keyes DC, Mader LE, et al. First report of survival in refractory ventricular fibrillation after dual-axis defibrillation and esmolol administration. West J Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;17(6):762-5. PMID: 27833686

- Johnson EE, Alferness CA, Wolf PD, et al. Effect of pulse separation between two sequential biphasic shocks given over different lead configurations on ventricular defibrillation efficacy. Circulation. 1992 Jun;85(6):2267-74. PMID: 1591840

- Stiell IG, Walker RG, Nesbitt LP, et al. BIPHASIC trial: a randomized comparison of fixed lower versus escalating higher energy levels for defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007 Mar 27;115(12):1511-7. PMID: 17353443

- Koster RW, Walker RG, Chapman FW. Recurrent ventricular fibrillation during advanced life support care of patients with prehospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008 Sep;78(3):252-7. PMID: 18556106

- Walsh SJ, McClelland AJ, Owens CG, et al. Efficacy of distinct energy delivery protocols comparing two biphasic defibrillators for cardiac arrest. Am J Cardiol. 2004 Aug;94(3):378-80. PMID: 15276112

- Morgan JP, Hearne SF, Raizes GS, et al. High-energy versus low-energy defibrillation: experience in patients at Mayo Clinic-affiliated hospitals. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984Dec;59(12):829-34. PMID: 6503363

- Saliba W, Juratli N, Chung MK, et al. Higher energy synchronized external direct current cardioversion for refractory atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Dec;34(7):2031-4. PMID: 10588220

- Pourmand A, Galvis J, Yamane D. The controversial role of dual sequential defibrillation in shockable cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Sep;36(9):1674-9. PMID: 29880409

- Daya MR, Schmicker RH, Zive DM, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival improving over time: results from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC). Resuscitation. 2015 Jun;91:108-15. PMID: 25676321

- Institute of Medicine. Strategies to improve cardiac arrest survival: a time to act. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015 Sep. PMID: 26225413

- Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG, et al. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation. 2010 Nov;81(11):1479-87. PMID: 20828914

- King County, WA, Has World's Highest Survival Rate for Cardiac Arrest | Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation. http://www.sca-aware.org/sca-news/king-county-wa-has-worlds-highest-survival-rate-for-cardiac-arrest. 2018.

- Rezaie S. Beyond ACLS: Is It Time to Abandon Epinephrine in Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest? - REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog. REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog. http://rebelem.com/time-abandon-epinephrine-hospital-cardiac-arrest/. 2018

Mark M. Ramzy, DO, EMT-P (@MRamzyDO)

Drexel University, Department of Emergency Medicine