It is that time of the year again! On or around November 1 each year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) releases final regulations that impact Medicare payments for clinicians and outpatient hospital services. CMS first issues proposed regs during the summer, and ACEP and other stakeholders have the opportunity to submit comments on the proposed policies in the regs. Then, CMS must review all public comments (including ours!) and issue final regs that go into effect at the start of the following calendar year (in this case, January 1, 2023).

Although I have already highlighted the major proposed policies and ACEP’s responses to both the CY 2023 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and Quality Payment Program (QPP) proposed reg and the CY 2023 Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) proposed reg in previous Regs and Eggs blog posts, I want to preview the major issues in each of the two final regs that we will be keeping our eye on. In the coming weeks, once the final regs are released, I will go more into depth on the major final policies and how they could affect you as emergency physicians and your patients.

PFS AND QPP POLICIES

Medicare Payment Cuts

As you all probably know, CMS proposed a 4.4 cut to the CY 2023 PFS conversion factor. Along with this across-the-board reduction, the 2 percent sequestration reduction continues to apply year after year. Furthermore, there is another “Pay-Go” sequester of 4 percent that is scheduled to begin at the start of 2023—making the total overall projected cut starting January 1 a whopping 10.4 percent.

ACEP strongly advocated in our comments on the PFS and QPP proposed reg for CMS to mitigate as much of the 4.4 percent conversion factor cut in the final reg as it could. However, it is unclear whether CMS will in fact reduce that cut by adjusting the changes it is making to specific codes and relative value units (RVUs). CMS also has no control over the 2 percent sequester and the 4 percent “Pay-Go” sequester.

Therefore, we are not counting on CMS to take much action (despite our comments and the concerns expressed by the rest of the physician community)—and we must instead depend on Congress. We need you to ask your Senators to help ensure that any year-end legislation includes efforts to halt these harmful cuts.

Please urge your Senators by October 28 to sign on to a bipartisan letter currently being circulated by Senators Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) and John Barrasso, MD (R-WY). It is critical that legislators hear from you about how devastating these cuts could be for access to emergency care for patients across the country.

Evaluation and Management, Observation, and Critical Care Services

In the proposed reg, CMS outlined three major sets of changes that will go in effect in 2023:

- Documentation Changes: As described in a Regs and Eggs blog post from a couple weeks ago, the American Medical Association (AMA) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) has implemented major documentation changes that will affect the emergency department (ED) evaluation and management (E/M) services at the start of the calendar year.

- Critical care: CMS proposed to change the threshold for reporting CPT 99292 in addition to the base code of CPT 99291 from 75 minutes to 104 minutes. ACEP noted in our comments that this proposed critical care policy differs from long-standing CPT policy, and we believe it will increase provider confusion and administrative burden.

- Observation Services: CMS proposed to accept the CPT coding changes that merge the codes previously describing observation services into the inpatient E/M code set.

ACEP is generally concerned with the overall ability of emergency physicians to adopt all the changes that CMS is proposing for 2023 due to staffing shortages and complications in workflow implementation. We had requested in our comments that CMS delay or phase in some of the changes to the observation codes and billing requirements, specifically the enforcement of the 8-to-24-hour rule related to observation encounters that transcend the calendar date. We are hopeful that CMS accepts this recommendation in the final reg and does decide to delay the implementation of the observation code changes. We will also be looking out for the resolution of the confusing critical care policy.

Furthermore, we expect CMS to finalize its proposal to delay the implementation of the full transition to using only time to determine the substantive portion of a split/shared E/M service until 2024. ACEP had supported CMS’ proposal, and we continue to push for the continuation of the current policy to use the history, physical exam, medical decision making (MDM), or more than half of the total time spent with a patient to determine the substantive portion of the split/shared visit. We strongly urge CMS going forward to revise the split or shared visit policy to allow the physician or non-physician practitioner who is managing and overseeing the patient’s care to bill for the service, thereby preventing the disruption of team-based care.

Finally, we will be monitoring whether CMS finalizes its proposal to reject the AMA Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) recommendation to decrease the work RVUs for ED E/M level 4 (CPT 99284) from the current value of 2.74 RVUs to 2.60 RVUs. This is an extremely common code billed by emergency medicine clinicians, and a reduction in work RVUs as the RUC recommended could reduce overall emergency medicine reimbursement by tens of millions of dollars. ACEP had previously argued that the ED E/M codes should retain their relative values as compared to the office and outpatient E/M codes. We appreciate that CMS gave credence to this argument in the proposed reg and hope that CMS continues to do so in the final reg by finalizing its proposal to reject the RUC’s recommended decrease.

Medicare Shared Savings Program

The Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) is the national accountable care organization (ACO) program, which serves over 11 million Medicare beneficiaries. In the rule, CMS proposed to make numerous changes to the program, fundamentally altering the program. These proposed changes include:

- Allowing for up-front advanced payments to be made to certain new Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs that could be used to address Medicare beneficiaries’ social needs.

- Giving smaller ACOs more time to transition to downside financial risk.

- Creating a health equity adjustment to an ACO’s quality performance category score to reward excellent care delivered to underserved populations.

- Adjusting the benchmark methodology to encourage more ACOs to participate. CMS states that these adjustments would help the agency achieve the goal of having all people with Traditional Medicare be in an accountable care relationship with a health care provider by 2030.

It will be interesting to see which of the changes to the MSSP CMS finalizes in the final reg. One policy that CMS did not propose, but that we recommended, was to create additional incentives for specialists like emergency physicians to get engaged in the MSSP and other ACO initiatives.

Requirement for Electronic Prescribing for Controlled Substances for a Covered Part D Drug under a Prescription Drug Plan or MA-PD Plan

In the PFS and QPP proposed reg, CMS had proposed to delay compliance of the electronic prescribing for controlled substances (EPCS) requirement by another year, until January 1, 2024, and sought comment on what penalties to implement going forward starting in 2025. As a reminder, the SUPPORT Act—the major law passed in 2018 that addressed the opioid crisis—required there to be EPCS in the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Program. This requirement was supposed to take effect in 2021 but has been delayed multiple times.

Once implemented, CMS will require 70 percent of prescription drug claims for Schedule II, III, IV, and V controlled substances under Medicare Part D to be electronically prescribed, after exceptions are applied. These exceptions include:

- Prescriptions for controlled substances issued when the prescriber and dispensing pharmacy are the same entity.

- Prescribers who issue 100 or fewer qualifying Medicare Part D controlled substance prescriptions per calendar year.

- Prescribers who CMS determines are in the geographic area of an emergency or disaster as declared by a Federal, State, or local government entity.

- Prescribers who have received a CMS-approved waiver because the prescriber is unable to conduct electronic prescribing of controlled substances due to circumstances beyond the prescriber's control.

In our comments on the proposed reg, ACEP had supported the proposal to delay the EPCS requirement and opposed the imposition of any financial penalties for those who do not comply with the requirements. In the past, we have tried to point out the unique factors that are specific to care provided in the ED that we believe CMS must take into consideration when implementing the Medicare requirement.

We had requested, but were not granted, a specific exception for patients who seek treatment in EDs. As you are well aware, the majority of ED visits fall outside of “business hours,” and some of your patients may have a regular pharmacy. Thus, many e-prescriptions are prone to “failure,” meaning the pharmacy hours are not convenient for the patient or the prescribed drug may not be in stock. This usually requires the patient to return to the ED or call you as the prescriber to cancel the original prescription and re-issue it to a new pharmacy. If your ED shift has ended, a new prescriber must be recruited, which either prompts a new and avoidable ED visit or pulls a clinician away from current emergency patients. Emergency physicians especially may have trouble electronically prescribing controlled substances in rural areas. In some areas of the country, there are no 24-hour pharmacies. Pharmacy hours can change frequently and getting even non-controlled prescriptions to an open pharmacy that the patient can use is problematic after business hours.

Further, we believe that in some cases, patients have a better chance of filling a prescription if they have a paper prescription in hand. Sometimes, patients who are electronically prescribed a controlled substance show up at the wrong pharmacy, and it can be burdensome for you to get the prescription transferred.

All in all, we still want CMS to create an exception for emergency physicians in cases where you feel, using your clinical judgment, that issuing an electronic prescription for a controlled substance would be logistically challenging and/or decrease the likelihood that their patient will actually get their prescription filled.

For now, without this ED exception in place, we hope that CMS continues to delay the implementation of the EPCS requirement.

The Quality Payment Program (QPP)

As a reminder, the Quality Payment Program (QPP) includes two tracks: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). MIPS includes four performance categories: Quality, Cost, Improvement Activities, and Promoting Interoperability (formally Meaningful Use). Performance on these four categories (which are weighted) roll up into an overall score that translates to an upward, downward, or neutral payment adjustment that providers receive two years after the performance period (for example, performance in 2023 will impact Medicare payments in 2025). Those who successfully participate in Advanced APMs can receive a five percent bonus and are exempt from MIPS. However, the last year a clinician can receive a bonus under current law is 2024, based on the clinician’s participation in the Advanced APM in 2022. Most emergency physicians do not participate in Advanced APMs, and therefore must meet the MIPS requirements.

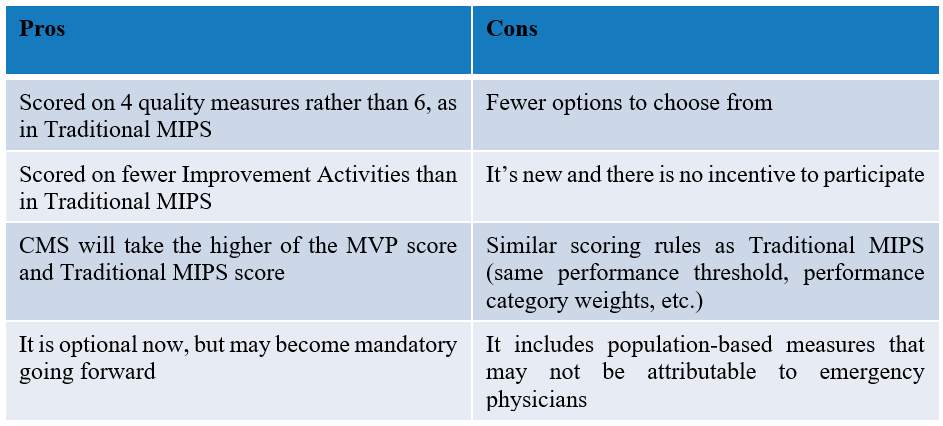

The 2023 performance year is the first year of a new reporting option in MIPS called the MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). MVPs represent an approach that will allow clinicians to report on a uniform set of measures on a particular episode or condition in order to get MIPS credit. ACEP developed an emergency medicine-focused MVP that CMS will be including in the first batch of MVPs starting in 2023. While we are excited about the implementation of this MVP, the Adopting Best Practices and Promoting Patient Safety within Emergency Medicine MVP, we are generally concerned that not many clinicians will actually report through the MVP next year.

Due to the COVID-19 public health emergency, hardship exemptions have been in place for the 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022 MIPS performance periods. Therefore, for some clinicians, 2023 may be the first time they participate in MIPS in four years. These clinicians may not be willing to take a risk and try a new method for reporting in MIPS, especially when the potential downside is significant – a nine percent reduction in reimbursement on all Medicare covered professional services. We also understand that clinicians can report both MVP measures and traditional MIPS measures, and CMS will take the higher of the two scores.

To encourage participation in MVPs, we had recommended the following:

- Create More Incentives for Participating in MVPs: ACEP believes that there should be some additional incentives for initially participating in an MVP over traditional MIPS. ACEP strongly recommends that CMS include at least a five-point bonus for participating in an MVP initially. Clinicians who participate in MVPs should also be held harmless from any downside risk for at least the first two years of participation.

- Eliminate the Foundational Layer: MVPs include a “foundational layer” of population-based claims measures. ACEP believes that measures that should be included in MVPs are only those that have been developed by specialty societies to ensure they are meaningful to a physician’s particular practice and patients and measure things a physician can actually control.

We are hopeful that CMS accepts these recommendations in the final reg. At this point in time, the pros and cons of participating in MVPs appear to be:

These pros and cons could definitely change depending on the final MVP policies that CMS includes in the final reg.

Beyond MVPs, CMS continues to increase other MIPS requirements. For example, CMS proposed to maintain the current data completeness threshold at 70 percent for the 2023 performance period but to increase the data completeness threshold to at least 75 percent for the 2024 and 2025 performance period. The data completeness threshold is the minimum percentage of eligible patients that clinicians must report on for each quality measure. ACEP had opposed the proposed increase in the threshold for the 2024 and 2025 performance periods because it would increase administrative burden and the overall cost of complying with MIPS requirements.

CMS also proposed to keep the performance threshold—the threshold that clinicians need to achieve in order to avoid a penalty— at 75 points in 2023. This is the same threshold the agency established for 2022. ACEP supported CMS’ decision not to raise the threshold in 2023 in our comments on the proposed reg, as 75 points is already an extremely high bar to meet.

Overall, we will monitor what final modifications CMS decides to make to MIPS in 2023 and hope that CMS decides to hold off on any policies that would increase overall burden and make it more difficult to successfully participate in the program.

OPPS POLICIES

Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs)

You may recall that the Consolidated Appropriations Act (enacted on December 27, 2020) included a provision that would allow critical access hospitals (CAHs) and small rural hospitals (those with less than 50 beds) to convert to REHs starting on January 1, 2023. REHs, once established, will receive enhanced reimbursement under Medicare. They will not provide any inpatient services but must be able to provide emergency services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The goal of this new facility-type is to help struggling rural hospitals stay afloat by allowing them to shed their inpatient beds and continue to operate with lower administrative costs. Thus, instead of closing, these facilities could continue to serve their communities and provide access to emergency care and other outpatient services. CMS proposed new Conditions of Participation (CoPs) for REHs in a stand-alone reg and numerous other policies in the OPPS proposed reg. All of these policies will be finalized in the CY 2023 OPPS final reg.

One of the major CoPs the CMS proposed relates to staffing requirements for REHs. The Consolidated Appropriations Act does not specify the specific type of physician and/or practitioner that must provide services within an REH, so CMS decided to grant REHs a great deal of flexibility to determine how to staff the emergency department at the REH 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. In the proposed reg, CMS stated that that it would not be necessary for a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or physician assistant to be available to furnish patient care services at all times in the REH. Instead, CMS proposed that a physician or practitioner with training or experience in emergency care be on call and immediately available by telephone or radio contact and available on site within specified timeframes.

In ACEP’s response to the REH CoP proposed reg, we stated upfront that physicians should supervise all care delivered by non-physician practitioners in REHs. When possible, board-certified emergency physicians should conduct that supervision, but we understand that, due to workforce issues, that is not always possible. When a board-certified emergency physician is not available, it is still critical that physicians experienced and/or trained in emergency medicine (such as family physicians) oversee care being delivered by non-physician practitioners in REHs. We also strongly opposed the proposal to not require a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or physician assistant to be physically present at REHs at all times. We believe that that if finalized, such a policy would pose significant patient safety concerns. It could also increase the chances that REHs violate the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) if a trained clinician is unable to arrive in time to perform a medical screening examination and stabilize the patient if the patient has an emergency medical condition. It is imperative that any time a patient comes to an REH with an immediate medical emergency, there will be clinician onsite to treat them IMMEDIATELY.

We hope that CMS accepts these recommendations in the final reg and enacts final policies that will support physician-led, team-based care in REHs. We are concerned that if CMS doesn’t modify its proposals around staffing, the quality of patient care could suffer and there could be significant safety issues. However, regardless of what final policies CMS enacts for REHs, it is unclear how many small hospitals or CAHs will actually convert to this new facility type in 2023.

Again, I will keep you updated on what final policies CMS enacts in both the CY 2023 PFS and QPP final reg and the CY 2023 OPPS final reg. In the meantime, hold the date of November 1st and make sure you get an extra helping of eggs—since major regs are definitely coming our way!

Until next week, this is Jeffrey saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs.