In a Regs and Eggs blog post from January, I discussed a promising proposal from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to add emergency physicians to the network adequacy requirements for Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchange health plans starting in 2023. Well, I’m happy to report that CMS decided to finalize this proposal in a final regulation that the agency released a couple of weeks ago!

Let me explain what this means and why this could be a big deal!

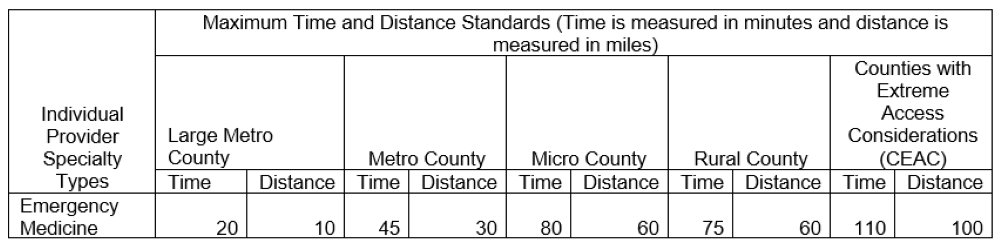

First, what does this mean? Private health plans that participate in the ACA federal Exchange must follow a set of rules, including adhering to certain network adequacy requirements (it is important to note that around 21 states operate their own Exchanges that may have different network adequacy rules and requirements). The health plans on the federal Exchange must ensure that 90 percent of their enrollees have “access” to at least one in-network provider/facility in a defined list of specialty types. Access is determined through a set of “time and distance” standards that vary provider type-by-provider type and county-by-county, depending primarily on whether the county is located in an urban or rural area. In alignment with Medicare Advantage’s approach, CMS classifies counties into five county type designations: Large Metro, Metro, Micro, Rural, and Counties with Extreme Access Considerations (CEAC). For more information on what these designations mean, click here and go to page 6.

Emergency physicians, who have been excluded from these standards up until now, have finally been added to the list! As you can see from the table below, health plans starting in 2023 will be required to ensure that 90 percent of their enrollees have access to an in-network emergency physician within 10 miles and a 20-minute drive in large urban areas and within 60 miles and a 75-minute drive in rural areas. The standards align with those set for inpatient hospitals and critical care services.

Enforcement of these standards is critical. Without stringent enforcement protocols, the standards themselves are essentially meaningless. CMS explains in a letter sent out to health plans that the agency will conduct reviews of in-network provider data that health plans submit to ensure compliance. Health plans that don’t comply must submit a detailed justification, including: the reasons that one or more time and distance standards were not met; the mitigating measures the plan is taking to ensure enrollee access to respective provider specialty types; information regarding enrollee complaints regarding network adequacy; and the plan’s efforts to recruit additional providers. CMS will use all the information provided by the health plan as part of the certification process to assess whether the plan meets the regulatory requirement prior to making the certification decision. CMS also states that it “will continue to monitor network adequacy throughout the year and will coordinate with state departments of insurance should it be necessary to remedy an issuer’s network adequacy deficiencies.”

Next, why could this be a big deal? As I stated in a previous Regs and Eggs blog post, ACEP has been concerned that health plans will use the No Surprises Act as an excuse to narrow their networks even further. Unfortunately, this is already happening, as numerous physician practices have already received unilaterally initiated termination notices from insurance plans for long-standing in-network agreements, including agreements that currently protect patients in rural and underserved communities. We hope that by including emergency physicians in the network adequacy requirements, private health plans may have more of an incentive to negotiate fairly with emergency physician groups, since they will be required to ensure that their enrollees have access to at least some in-network emergency physicians.

All in all, this new policy is a very good development. ACEP has pushed CMS for years to strengthen network adequacy requirements. While much of our advocacy has been focused on getting CMS to add emergency physicians to its Medicare Advantage network adequacy standards, we will definitely take this policy victory!

Now, we have to wait and see if this policy actually does lead to more good-faith contract negotiations between private health plans and emergency physician groups. Again, one major factor that will make or break the success of the policy is enforcement. Although CMS has a solid enforcement strategy in place, it remains to be seen if CMS and/or states will actually take stringent actions against health plans that fail to comply—such as de-certifying the plans and kicking them off the ACA Exchange. Only time will tell!

Until next week, this is Jeffrey saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs!